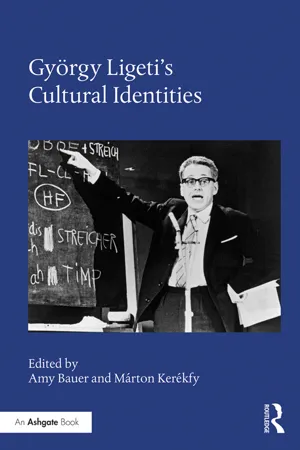

Sender Freies Berlin broadcasts from the Congress Centre an international lecture series, Music in the Technological Era.

HANS HEINZ STUCKENSCHMIDT

Ladies and gentlemen, with today’s talk we close the series of 12 lectures Music in the Technological Era. It has been presented, beginning in November 1962, by the Foreign Office and the Faculty for Humanities of the Technische Universität Berlin at the Congress Centre and broadcast for television by the Sender Freies Berlin. Our guest today is György Ligeti, and, following our usual procedure, I will give you a few facts about his personal history.

Ligeti was born in Transylvania in 1923. He first studied composition in Klausenburg3 from 1941 to 1943, and continued these studies in Budapest at the Music Academy with [Ferenc] Farkas and [Sándor] Veress from 1945 to 1949. He spent some time collecting folk music in Romania und became in 1950 a professor of harmony, counterpoint and musical forms at the Budapest Music Academy.4 He occupied this post until 1956 when he emigrated during the revolution and settled first in Vienna and temporarily in Cologne. Since 1957 he has been working at the Studio for Electronic Music of the Westdeutscher Rundfunk [West German Radio in Cologne], and we also know him as a lecturer at the Darmstadt-Kranichstein courses.5 The friends of new music also know him from the many performances of his works in the diverse concert series organised by German Radio broadcasters and by the Donaueschingen Festival in 1961. Ligeti has written choral and orchestral works, chamber music, piano music and songs [Lieder]. His first electronic composition was Artikulation, in 1958, which was followed by Apparitions for orchestra in 1960,6 and, after that, Atmosphères, which was performed in Donaueschingen and here at Sender Freies Berlin. Then there is a work for organ, Volumina, and finally a work which has yet to be performed, Aventures. Ligeti not only is a composer but has also distinguished himself as a writer on music. He wrote a study of polyphony in Romanian folk music in 1953.7 He also published a proper harmony book and in 1956 a two-volume treatise on classical harmony.8 Many of you will know his important and, for the most part, in-depth articles in two issues of the avant-garde review die Reihe, nos. 4 and 79 [the cover of no. 7 is shown], and in the 1960 edition of the Darmstädter Beiträge.10 I now give the word to Professor György Ligeti.

GYÖRGY LIGETI

Ladies and gentlemen, on this Rosenmontag11 Professor Stuckenschmidt has kindly invited me to speak to you about my own compositions. I must admit, however, that I have rather mixed feelings about this task, namely because composition is a very intimate activity and one is a bit embarrassed when one has to or wants to speak about it. Therefore, I am also embarrassed but not very much, only a bit. One wants to present, or communicate, only a finished work, but how the work was made, that is a private matter and, apart from the composer’s, is nobody else’s business. Sometimes it’s very awkward when composers speak of their own theories as I am about to do, and maybe not always that interesting, although sometimes it is. So, even if it is a very private intimate thing, one can overcome this feeling of awkwardness because composers, including myself, – yes, I too am conceited, like all composers or like all people, like you, you, like all of you, and I like to speak about myself as you also do. Who would not like to speak about themselves? And so, as I said, one can get over this little bit of awkwardness, and so I will try to inform you about myself, my thoughts about composition, my methods and views, etc.

I must say, and this is nothing new, that the most important thing in composing is that you cannot really talk about it, it’s intuitive. If one is Freudian, one would say it happens on an unconscious level; if one is not, then one does not speak about it as it takes place at an inner emotional level of which one is ignorant. I know myself that I have sometimes analysed works from other composers, and when these composers were dead, then my analyses were very exact. But sometimes I also made the mistake of analysing works of composers who were still alive, and sometimes discovered things that the composers themselves didn’t know. It is possible that I was mistaken, but it is also possible that the composer in question composed musical relationships and situations of which he was not even aware. Because of this it is always suspect when a composer speaks about his own works because he knows a lot of things but not everything.12 We can say that composing consists of two parts: one part is completely spontaneous, intuitive, coming from the unconscious, and then there is the speculative part, something that is rationally organised, but this is like a cake with icing on top. What is rational comes later; it is an added ingredient. I don’t think that one can compose purely speculatively, that is, only with theories. You can do it, and many do, but listen to those compositions… I only speak in general and not about particular composers, who are nearly all my very good friends and whom I don’t really want to insult in front of you. You can think of whom you like. I think music is a bit like love – you do it, but you don’t talk about it. It’s a bit suspect if you speak about it very much. You can describe the techniques, but the composition itself can’t be described, can’t be defined, thank God. Thank God there is not a valid aesthetic theory yet; if it did exist then everyone would have nice recipes on how to do it and everyone would diligently compose or paint pictures, etc. But that doesn’t exist, and that’s very good. I hope that there won’t ever be one – an exact scientific description of the composition process.

However – I just mentioned the word science – today it’s fashionable to confuse science with art and many want…, not only composers, but also critics or other people, the public, etc., who believe that the new art is something scientific, especially the new method of composing – composers even have books of logarithms and tables and such things. I believe that one shouldn’t confuse science with art. I must say that there was a time when I myself leaned towards understanding composition as an exploration of sound material, but I was on the wrong track. I believe that just as composing is not only spontaneous but also a thing of the brain, vice-versa, composing cannot be only a thing of the brain, but must be a thing of the heart. That’s the way it is; everyone, also composers sometimes, is only human – they have a heart and a mind. There are people who think that only what comes from the brain is legitimate, what is speculatively accurate and what one can prove. There are others who imagine composers as they were envisioned in the nineteenth century, with long hair the way Beethoven was portrayed in paintings,13 who sit at the piano and to whom the composition flows somehow. Of course, both of these images are incorrect. The composer reflects, has ideas and then mulls them over. You drop a lot of them, others you pursue; there are maybe very speculative ideas, plans, etc. For instance, an architect has plans for a house, but that is not the most important thing – it is also important – a composition, just like a house, would collapse if it is not well built, well structured. Now, with a piece of music, it’s not as dangerous as with a congress centre,14 but even so, one has to plan carefully; therefore, one must check out much of the process rationally but, as I said, not everything. I believe that a good blend of, if you wish, heart and brain can lead to valid compositions.

However, there is a point where science and music are similar, and that is when the scientist seeks to explore new areas in order to find something new. In the same way the composer, if he is really a composer and not an imitator, always tries to do something new, to look for new possibilities of structuring his material, especially music, which has no real material, unlike the sculptor who has stone, or some kind of fabric or colour for the painter, or even language for the poet – everything that is somewhat tied to some material – whereas notes are not the material of music; rather, it is the relationships between the notes which are the material, and it is this that one can shape as one wishes. The connection between the notes, the sound complexes, the relationships is historically given. There are certain earlier styles, established forms: sonata form, rondo form, etc., which are, however, all formal preconceptions. The composer wants to free himself from these and thinks: ‘I imagine a music which has never been heard before, and I know nothing of what is currently being done, or has been done in the past.’ Obviously, I do know the past; there is a layer of tradition somewhere in all composers, but I believe that the aim of today’s composers is to throw themselves into completely new areas where no one has ever been, in a field that is not unexplored but where there is ‘unheard’ music, unheard here in the musical sense.15 Our series of talks is entitled Music in the Technological Era, and I must say that I don’t think today’s music is especially touched by technology. For instance, technical possibilities are used to compose or realise electronic and other types of music, but that is not the essential thing about it. An organ or a flute also has a mechanism. Music has always been tied to technology. The important thing in music, its structuring, is not technical, or rather is minimally influenced by technology.

Well, I’ve said that every composer wants to explore new areas which have never been heard before, where he himself then produces something new. And it is the fashion nowadays that every composer has a special area in which he takes out a patent at some kind of creative patent office, and then he has it and that’s what he does. And that is very good from a business point of view because the public, the critics and all the organisations know that ‘aha, this is the electronic composer, this is the serial composer, this is the post-serial composer, this is the non-serial composer, etc.’, and everybody gets their stamp, and everyone knows what they are dealing with. This is much worse with painters: one paints only in yellow, the other only with washcloths, the third works only with garbage cans, one only sprays, the other shoots, etc. I must say that all these techniques appeal to me very much, and I am certainly not against modern art. I hope that I too make new art. But I hate one-sidedness. I hate any kind of labelling, any branding. Composers are too easily branded: Schoenberg the dodecaphonic composer, or Boulez the serialist, or Stock-hausen the electronic music composer, or Messiaen the rhythmist, or Cage the dice thrower, etc. But it was always like that. Just think of Debussy the impressionist, or Mahler the last great symphonist, although many think that Bruckner was the last great symphonist, and not Mahler. But that is a bit like a book which was very popular in my childhood, [James Fenimore] Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans; these titles and labels are all incorrect. Mahler was not the last symphonist. Stockhausen is not the electronic music composer; he also composes wonderful instrumental music. Boulez also has non-serial pieces. Probably Schoenberg’s most important works are not dodecaphonic but written in free atonality, etc.

I’ve been labelled – this is a new label because I’ve only just become known in the past few years, but still I do have a label: Ligeti the Klangfarben-mixer or something like that; I’m the Klangfarben-composer.16 Supposedly because I always put together new Klangfarben, which is true and not true. It’s true that I’...