![]()

Thomas Risse and Nelli Babayan

Otto-Suhr Institute of Political Science, Department of Political and Social Sciences, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany

This special issue examines Western efforts at democracy promotion, reactions by illiberal challengers and regional powers, and political and societal conditions in target states. We argue that Western powers are not unequivocally committed to the promotion of democracy and human rights, while non-democratic regional powers cannot simply be described as “autocracy supporters”. This article introduces the special issue. First, illiberal regional powers are likely to respond to Western efforts at democracy promotion in third countries if they perceive challenges to their geostrategic interests in the region or to the survival of their regime. Second, Western democracy promoters react to countervailing policies by illiberal regimes if they prioritize democracy and human rights goals over stability and security goals which depends in turn on their perception of the situation in the target countries and their overall relationships to the non-democratic regional powers. Third, the effects on the ground mostly depend on the domestic configuration of forces. Western democracy promoters are likely to empower liberal groups in the target countries, while countervailing efforts by non-democratic regional powers will empower illiberal groups. In some cases, though, countervailing efforts by illiberal regimes have the counterintuitive effect of fostering democracy by strengthening democratic elites and civil society.

Recent events in Ukraine have shown in a nutshell what this special issue is about. Abiding by strong pressures from Russia, the ousted Ukrainian President, Viktor Yanukovych, refused to sign the Association Agreement (AA) with the European Union (EU), which would have brought the country closer to the West. Mass demonstrations dubbed “Euromaidan” erupted against a corrupt and undemocratic regime. The resulting turmoil and violence led to various and initially rather uncoordinated mediation efforts by the United States (US) and the EU. When the Yanukovych government collapsed and an unelected transition government took over, Russian forces annexed the Crimean peninsula, instigating what some called the worst international crisis in Europe since the end of the Cold War. In Eastern Ukraine, Russian-supported rebel forces have engaged in a military conflict with the democratically-elected Ukrainian government, creating an area of limited statehood in the process in which the Ukrainian state is no longer able to enforce the law.1

Alternatively, take the events of the “Arabellions”: for years, the US and Europe alike contributed to the stabilization of authoritarian regimes in North Africa for fear that sudden change would bring anti-Western and Islamist governments into power. At the same time, they cautiously supported civil society movements. Nevertheless, the Arab uprisings took Western powers by surprise and their reactions were slow and inconsistent.2 They collaborated to prevent mass killings in Libya and intervened militarily with the UN Security Council, invoking the “responsibility to protect” (R2P). However, when Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states put down the uprising in Bahrain and when Russia (and China) blocked action against Syria in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), the US and the EU ceased to respond more forcefully to what arguably have been mass atrocities and severe human rights violations.

The starting point of this special issue is the state of the art in the literature on transatlantic democracy promotion. This literature has shown that distinguishing the US as a “hard” power and the EU as a “soft” power is no longer valid.3 Comparative studies of American and European democracy promotion programmes show that the two have converged with regard to goals, strategies, and instruments.4 The literature has also looked into the substance of EU democracy promotion5 and the EU’s move from “leverage” to a “governance” model of promoting democracy.6 Moreover, both the US and the EU rarely prioritize democracy and human rights in their foreign policies, but usually prefer stability over democracy7 as has become obvious in their bewildered reactions to the “Arabellions”. Various studies have also investigated conflicting objectives of initiating democracy promotion, but have so far focused only on the internal considerations of the US and Germany.8 As to the effects of democracy promotion, scholars have focused predominantly on the domestic politics and societal conditions in target states as the main variables to explain democratization outcomes.9 At the same time, there is also an emerging literature on “autocracy promotion”.10 It suggests that autocracy promotion may include deliberate diffusion of authoritarian values, borrowing of foreign models, assisting other regimes to suppress democratization, or condoning authoritarian tendencies.11 The motivations for such actions have been explained by considerations of rent-extraction from target countries or by efforts to prevent democratization spillover,12 while its effects have been explained by the balance of power between illiberal and liberal domestic elites.13

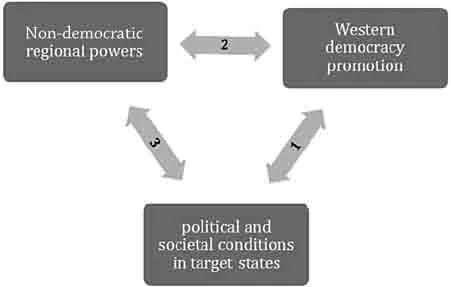

This special issue looks at the entire triangle: Western efforts at democracy promotion, reactions by illiberal challengers and regional powers, and political and societal conditions in target states (Figure 1). We examine in detail the challenges of selected non-democratic or illiberal regional powers14 – Russia, China, and Saudi Arabia – to Western (US and EU) efforts at democracy promotion. We argue that Western powers are neither unequivocally committed to the promotion of democracy and human rights nor can non-democratic regional powers simply be described as “autocracy supporters”.

Figure 1. The focus of the special issue.

This special issue focuses on three sets of interrelated interactions:

• Interactions between Western efforts at democracy promotion and socio-political conditions in target states (arrow 1 in Figure 1);

• Interactions between illiberal regional powers and Western democracy promoters (arrow 2 in Figure 1);

• Interactions between illiberal regional powers and social and political actors in target states (arrow 3 in Figure 1).

This focus leads to three questions that this special issue tries to answer:

(1) How do non-democratic regional powers react to EU/US efforts at democracy promotion in target countries? In other words, which combination of Western democracy promotion and local conditions produces which reaction by illiberal regional powers?

(2) If non-democratic regional powers adopt countervailing policies, how do the US and the EU react to the policies of illiberal regional powers toward target states?15

(3) Which local effects do different combinations of Western policies and those of non-democratic regional powers produce? That is, how do the policies of non-democratic regional powers affect democracy promotion efforts by the US and the EU in target countries?

In response to the first question, we argue that illiberal regional powers are only likely to respond to Western efforts at democracy promotion in third countries if they perceive challenges to their geostrategic interests in the region or to the survival of their regime. We also suggest that non-democratic regional powers are unlikely to intentionally promote autocracy even though “autocracy strengthening” might be the consequence of their behaviour.16 In some cases, illiberal regimes even promote democracy if it suits their geostrategic interests.17

In response to the second question, we claim that Western democracy promoters will only react to countervailing policies by illiberal regimes if and when they prioritize democracy and human rights goals over stability and security goals, which depends in turn on their perception of the situation in the target countries and their overall relationships to the non-democratic regional powers. As a result, the US and the EU might react differently to countervailing policies even though their strategies and instruments with regard to human rights and democracy promotion are similar.

With regard to the third question of the effects on the ground, this mostly depends on the domestic configuration of forces, both government and civil society.18 Western democracy promoters are likely to empower liberal groups in the target countries, while countervailing efforts by non-democratic regional powers will empower illiberal groups. The differential empowerment of domestic forces depends in turn on the leverage of the EU and the US powers as compared to that of illiberal regional powers in terms of credibility of commitment, legitimacy, and resources. It also depends on economic and security linkages between the target state, on the one hand, and the Western powers as compared to the non-democratic regional powers, on the other.19 As a result, Western democracy promotion and countervailing efforts by illiberal powers may sometimes have counterintuitive results: the US and the EU might actually foster illiberal outcomes, while autocratic regimes might promote democracy, albeit unintentionally.20

This introduction to the special issue elaborates on each of three questions raised above. We then proceed with a survey of US and EU strategies and instruments of democracy promotion, possible actions of non-democratic powers, followed by an overview of t...