- 140 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Michel Foucault and Education Policy Analysis

About this book

The work of Michel Foucault has become a major resource for educational researchers seeking to understand how education makes us what we are. In this book, a group of contributors explore how Foucault's work is used in a variety of ways to explore the 'hows' and 'whos' of education policy – its technologies and its subjectivities, its oppressions and its freedoms. The book takes full advantage of the opportunities for creativity that Foucault's ideas and methods offer to researchers in deploying genealogy, discourse, and subjectivation as analytic devices. The collection as a whole works to makes us aware that we are freer than we think! This book was originally published as a special issue of the Journal of Education Policy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Michel Foucault and Education Policy Analysis by Stephen Ball, Stephen J. Ball in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Participation as governmentality? The effect of disciplinary technologies at the interface of service users and providers, families and the state

Faculty of Education and Children’s Services, University of Chester, Chester, England

This paper examines the concept of participation in relation to a range of recently imposed social and education policies. Drawing on recent empirical research, we explore how disciplinary technologies, including government policy, operate at the interface of service users and providers, and examine the interactional aspects of participation where the shift from abstract to applied policy creates tensions between notions of parental responsibility and empowerment, participation and ‘positive welfare’. In this, our analysis raises three important issues/questions: whether existing mechanisms for engagement between service users and service providers enable any meaningful participation and partnership in decision-making; whether multi-agency service provision is successfully incorporated within a participatory framework that allows service users to engage across and within services; and whether on the basis of our findings, there is requirement to remodel mechanisms for participation to enable user-experiences the opportunity to shape the way that services engage with families.

Introduction

This paper questions the political wisdom of consecutive social and education policies, which while promoting a positive rhetoric of participation and partnership between families and the state, produce seemingly little compelling evidence of such activity in practice. We suggest the shift from abstract to applied policy produces tensions between service users and providers, which gloss over important interactional aspects of participation, with the effect of marginalising the voice of those for whom such policies were originally intended. The outcome is one that pays ‘lip-service’ to participation through a process in which tacit forms of ‘government’ produce division and classification often leading to marginalisation. This issue is further intensified in a moral and political climate in which the government’s Welfare Reform Bill (for example, the ‘populist’ family benefits cap [Ross 2012]) has served to heighten the risk to vulnerable families and those in serious need of welfare support. Such issues, we suggest, reflect a pervasive culture in which affirmative discourses of participation, presented to enhance welfare, are fundamentally challenged by mixed messages and counterveilling discourses. Thus, the participation of all families, not least the vulnerable, is apparently undermined by moves in contemporary policy and the determination to promote greater parental responsibility. With this in mind, we draw on Foucault’s work (1977, 1979, 1980, 1983, 1991, 2002a, [1972] 2002b) to show the genealogy of policy reform dating back to the beginning of New Labour’s first term in office in 1997, and proceeding through the coalition settlement post 2010, in order to raise critical questions concerning the nature of participation and governmentality, both in response to recent reforms and the findings of our empirical research study.

During the lifetime of the previous Labour government (1997–2010), the nature and purpose of social and education policy and legislation relating to children and the family was characterised by a rhetoric of participation and partnership (Ball 2007). Parents/carers and children were identified as important stakeholders in decision-making processes in education, health, welfare and the justice system (DCSF 2007; DfES 2007; HMT/DfES 2007). For example, the Code of Practice for Special Educational Needs (SEN) outlined the rights and responsibilities of parents engaging in the SEN process and the partnership principles that it sought to sustain, recognising that parents have ‘a critical role to play in their child’s education’ and that positive attitudes towards parents are important (DfES 2001, 16). Subsequently, Aiming High for Disabled Children (AHDC) (HMT/DfES 2007, 16), included participation as part of a ‘core offer’, stating that

disabled children and their families have the option to be fully involved in the way services are planned, commissioned and delivered in their area, increasing their choice and control … putting families in control of the design and delivery of their care package and services

and ‘supporting parents to shape Services’. In the same year, the Children’s Plan stated that: ‘services need to be shaped by and responsive to children, young people and families, not designed around professional boundaries’ (DCSF 2007, 6), and that ‘partnership with parents is a unifying theme of the Children’s Plan’ (DCSF 2007, 8).

Each of the documents has proposed changes to the system of educational and welfare provision that draw upon varying degrees and notions of parental responsibility and empowerment. In Foucauldian terms, policy effectively speaks into existence a series of regulatory duties and responsibilities, which through a lexicon of new terms and punitive sanctions serves to construct the ‘responsible parent’ as a recognisable object of discourse. For example, Every Child Matters emphasised the mechanisms of ‘support’ for parents, while also introducing such punitive measures as parenting orders, home visiting and parent education programmes as part of a move towards ‘compulsory action with parents and families’ (DfES 2003, 43) identified as harder to engage. Thus, parents can be ‘read’ both as objects to be supported and as subjects of improvement, working on themselves and their imputed potential inadequacies. One year later, Removing Barriers to Achievement (DfES 2004) placed emphasis on building parents’ confidence in schools and the wider workforce by improving multi-disciplinary provision and accountability. Whilst parental involvement and confidence was the focus of AHDC, using the term ‘empowerment’ in relation to parental participation, introducing the Parents’ Charter and suggesting that parents (and children) would be involved directly in developing services and designing packages of care, paradoxically in the same year the Every Parent Matters agenda placed emphasis on parental responsibility:

government must pay particular attention to parents, for whatever reason, who currently lack the motivation, skills or awareness to do so. We must ensure that all parents have every chance to get involved, have their say and secure what is best for their children. (DfES 2007, 6)

It further added that ‘compulsion for the few, through measures such as parenting orders, may sometimes be required’ (ibid.).

The prevalance of such discourses and their corresponding practices serve to objectify parents and further construct a field in which parental participation is first classified, then normalised (Foucault 1977) and finally, governed (Foucault 1979). Thus, an ongoing concern regarding the development of policy is the extent to which parental participation can be viewed as authentic partnership or indeed whether notions of ‘empowerment’ simply masquerade as such. In Foucauldian terms, the rationality and discursive regularity of such notions of participation and empowerment can be seen to convey an ‘effect of power’ (Foucault 2002a, 132) and ‘truth’, in which it is useful to ask who is the ‘transmitting authority’ (Foucault [1972] 2002b, 106) in the policy-making process, and who is the intended subject? We suggest the historical lineage of policy to enhance participation may well have several trajectories and networks of determination (Foucault [1972] 2002b, 5), and so, our interpretation can be neither definitive nor complete. Rather, it reflects the particular nuances that characterise notions of participation and partnership; the diffuse structures through which service users become the subjects of disciplinary technologies. Such technologies produce a subtle effect, a ‘means of correct training’ (Foucault 1977, 170–194) that operates upon, and at the nexus of service users and providers, creating a context for continuous observation, examination and unremitting classification and regulation. This site of knowledge concerning discourses of ‘acceptable parental participation’ in turn provides the requisite conditions for the effective functioning of power, thus making knowledge (i.e. policy) function as ‘truth’. In Foucault’s (1980, 131) idiom, this represents a general politics of truth, a ‘regime of truth’, reflecting a panoply of complex partnership settings, where service users qua participating parents are constructed as the masters and servants of their own regulatory subjection, giving rise to, and further reinforcing the art of government (of which, more later).

Consequently, the above policy agenda serves to construct a potent and often somewhat exacting discursive practice, where such ‘truth’ is seen as increasingly pertinent to the process of reducing social disadvantage through engagement with ‘excluded communities’ (Churchill and Clarke 2010). In addition, the voice of those people least heard is one that is most frequently identified in discussions around solving ‘social problems’ (Gillies 2005). Closer examination of such rhetoric, however, reveals a form of government (Foucault 1979) of tensions in the way that policy discourse speaks into existence parental participation ‘on the ground’. In an examination of service user participation across the public services, Barnes, Newman, and Sullivan (2007) identify a variety of discourses of participation within and throughout the ‘New Labour’ policy agenda which are seen to influence the extent and success of public participation. More recently, Morris and Featherstone (2010) suggest that this policy trajectory has increasingly viewed children as ‘objects’ of discourse and hence policy, where relationships between children, parents and the family are treated more commonly as separated and problematic. As Foucault might suggest, such discourses of participation do not refer to the ‘distant presence of an origin’, but rather emerge in situ and should, therefore, be treated as and when they occur ([1972] 2002b, 28). For us, this is significant, not least for it suggests that the meaning of policy intended to enhance parental participation emerges as part of a complex interplay between different exemplar policies and through the interpreted space between discourse and its corresponding practice.

Conceptualising parental participation

Participation and engagement of service users in decision-making is routinely cited in social and education policy documents as a determinant of success in areas of ‘joined-up’ family-focused policy. Much of the policy discourse on the participation of service users, however, focuses on the development of ‘service-user friendly’ policies, failing to recognise or account for the tensions and competing discourses (Pinkney 2011) that have been persistently reported at the interface of families and service providers (for e.g. Carr 2007; Hess, Molina, and Kozleski 2006; Hodge and Runswicke-Cole 2008; Morris and Featherstone 2010).

A number of existing models of participation (for e.g. Arnstein 1969; Pugh et al. 1987; White 2000; Wilcox 1994) and specifically those in relation to children’s participation (Hart 1992; Lansdown 2005) place family–professional relationships along a continuum.

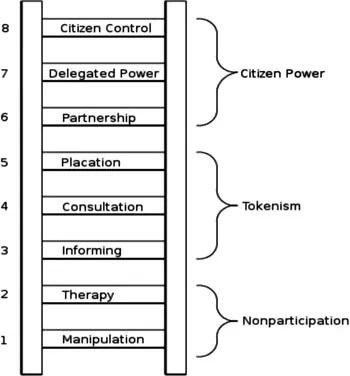

The different levels at which individuals can be involved in decisions have been depicted as steps on a ‘ladder of participation’ (Arnstein 1969), a model that illustrates participation relevant to a particular situation and the power balances involved (Wilcox 1994), which have been much cited in recent policy (for e.g. DCSF 2007; National Youth Agency/Local Government Association 2008; Welsh Assembly Government [WAG] 2006) and have been a ‘touchstone for policy makers and practitioners promoting user involvement’ (Tritter and McCallum 2006). As this typology suggests (see Figure 1), the lower rungs of the ladder represent degrees of non-participation inasmuch as they represent ways that service users might be influenced by service providers to affect change, to fit a required mould or to conform with the status quo. Thus, these levels are seen as manipulative. Using Foucault, and following Morgan’s (2005, 344) analysis of the SEN system, we suggest that this ladder of participation is apt to display a ‘panoptic structure of disciplinary power’.1 That is, in moving upwards, information is provided to service users with mechanisms put in place that prescribe what counts as acceptable parental participation. This is not a form of repression, but rather an apposite example of the way disciplinary power is able to operate through the administrative rules of the service provider, their boundaries and expectations to assure ‘the automatic functioning of power’ (Foucault 1977, 201). However, we contend that only when power is more equally balanced and dispersed between service users and providers are parents actually enabled to exploit it more creatively, through a process of ‘reciprocal determination’ (Foucault 2002b, 33), and by planning, co-constructing and delivering services in a shared and essentially non-linear way.

More recent conceptualisations by Wilcox (1994) and White (2000), have provided a focus on the process of participation; however, these models also fail to account for the ‘interplay’ and complexities of engaging with multiple services, which are of particular relevance to ‘problem’ families identified within ‘excluded communities’ who may well encounter a range of interventions and support from multiple agencies. Hudson (1997) does discuss the complexities of collaboration in multi-agency service provision, but this is done from the practitioner perspective, without accounting for how service users qua participating parents are engaged in a process of government (Foucault 1979). Wilcox’s model identifies five levels of participation, including information, consultation, deciding together, acting together and supporting independent action, however, when applied in practice, it is stated that ‘different levels are right in different circumstances’ (WAG 2006, 5), thus emphasising the panoptic structures of family-focused services in particular settings.

Figure 1. Ladder of participation (Arnstein 1969).

This being the case, a recurring problem with such models lies with making the uptake of help and support a conditional element of effective partnership, the administrative rules of which comprise the panotic apparatus and conditions in which normalising judgements (Foucault 1977; Morgan 2005) are made. Any deviation from the norm, in which there is an expectation that parents will engage with support networks, may be viewed as unacceptable, as socially deviant and, by association, regarded as ineffective parenting. The corollary is that emerging difficulties identified within educational settings may then be attributed directly to those parents whose imputed deficiencies prevent them from engaging with the system. In this way, policy operates to ‘objectivize’ the parent–subject through what Foucault (2002b, 50) calls a ‘dividing practice’, separating ‘good parents’ from ‘bad parents’. As Foucault (1977, 184) argues ‘the techniques of an observing hierarchy and those of a normalising judgement … make it possible to qualify, to classify and to punish’, thus separating the notion of acceptable partental participation from other forms of non-compliant conduct via the art of government. This panoptic structure and its disciplinary technologies are exemplified in a statement by David Cameron, who recently suggested that ‘the hard core minority of families’ who feature in statistics on discipline and truancy in school should have child benefits taken away (The Telegraph 4th September 2011).

While the panoptic metaphor suggests that power is a pervasive phenomenon in the education policy-making process, the concept of governmentality may fail to account for the nuances of social difference and thus ignore the important complexities of social location by assuming that power is apt to fall evenly upon its subjects (Mckee 2009). The corollary is an oversight of the possibility that some parents may be unable to participate effectively or, indeed, in a way that is deemed ‘acceptable’ under the purview of the normalising gaze. In such circumstances, parents may require a more explicit ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Citation Information

- Notes on Contributors

- 1. Participation as governmentality? The effect of disciplinary technologies at the interface of service users and providers, families and the state

- 2. Thriving amid the performative demands of the contemporary audit culture: a matter of school context

- 3. Discourses of merit. The hot potato of teacher evaluation in Italy

- 4. A genealogy of the ‘future’: antipodean trajectories and travels of the ‘21st century learner’

- 5. The policy dispositif: historical formation and method

- 6. Opening discourses of citizenship education: a theorization with Foucault

- 7. Changing policy levers under the neoliberal state: realising coalition policy on education and social mobility

- Index