![]()

Truancy and well-being among secondary school pupils in England

Gaynor Attwooda and Paul Crollb

aFaculty of Arts, Creative Industries and Education, University of the West of England, Bristol, UK; bInstitute of Education, University of Reading, Reading, UK

The paper considers two problematic aspects of the lives of young people: the long-standing issues of truancy from school and more recent concerns about the extent of mental well-being. It uses data from a large-scale survey, the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE). LSYPE provides a very large sample which allows for robust analysis of sub-groups within the population, data from families as well as the young people themselves and a panel design, so that characteristics of the young people at one point in time can be related to later outcomes. The results show the extent of truancy among year-10 pupils with well over one in five reporting truanting but high levels of truancy much less common. The reasons given for truancy mostly revolved around dislike of aspects of school. Truancy, even at low levels, was associated with more negative outcomes such as poor examination results and later unemployment. Data on mental well-being, based on the General Health Questionnaire, showed the extent of feelings of distress and inability to cope with everyday life with more serious levels affecting perhaps one in five of the young people. Young women were more likely to report problems of mental well-being than young men and truancy was strongly associated with poorer levels of well-being. The contrast between the way that most truants said that it was important to them to do well at school but also that disliking school was given as a reason for truancy suggests the possibility of school interventions.

Introduction

A number of papers in this issue of Educational Studies have discussed the issue of truancy and strategies for reducing truancy levels in schools. They have also made it clear how stubborn is the problem of unauthorised absence from school and its resistance to strategies to reduce it. In a recent book on school attendance, Reid draws on wide-ranging evidence to conclude that, “… improving school attendance and reducing truancy can be very difficult to achieve and, according to some reports, has remained little changed over the past thirty or more years” (2014, 3). He also demonstrates that this is not just a UK phenomenon but is repeated in other developed countries, especially the USA. In an earlier article (Attwood and Croll 2006), we quoted a report by the National Audit Office (2005) showing that the very substantial sums of money spent by the UK government on initiatives to reduce truancy had not resulted in any reduction in rates of unauthorised absence.

In our earlier study (Attwood and Croll 2006), we used large-scale survey data from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) to study various aspects of truancy based on interviews with a national sample of young people and their parents. This analysis provided extensive evidence on the prevalence of self-reported truanting behaviour and its association with personal characteristics of the young people and various aspects of their experiences of and attitudes to school. Because parents were also interviewed, truancy could also be related to family characteristics such as parental monitoring of the child’s education and the socio-economic status (SES) of the family based on occupation. And because the BHPS is a panel study, it was also possible to relate levels of truancy to later outcomes such as examination results, participation in post-compulsory education and employment.

The results showed a steady increase in rates of self-reported truancy through the years of compulsory secondary education. Children reporting truancy at either several times or often increased from just over 1% in year 7 (the first year of secondary school) to just under 10% in year 11 (the last year of compulsory schooling). It was also noticeable that the biggest jump in truancy levels occurred between years 9 and 10. Girls and boys reported similar levels of truanting behaviour. The longitudinal nature of the BHPS study made it possible to look at the association of truancy with later outcomes. These showed a uniform picture of increasing levels of truancy being associated with increasing levels of negative outcomes. At the extremes, the comparison of those reporting never truanting and those reporting often truanting showed that the truants were three times less likely to stay in education post 16, were three times more likely to have no good GCSE passes and were ten times more likely to be unemployed six months after leaving education.

The study also showed a number of personal and family characteristics that were predictors of truancy. Children from families in lower socio-economic groups, children of parents who did not monitor homework, children who had poor relationships with their teachers and children who did not put a high value on school were all more likely to truant than other children. But unlike the results of some other studies (e.g. Kinder, Wakefield, and Wilkin 1996; Reid 1999), concerns over bullying were not associated with truancy. Although these patterns of association were consistent and statistically significant, it was also the case that they were not particularly strong. For example, not monitoring homework was associated with truancy but nevertheless most truants were from families where homework was monitored and over half the children whose homework was not monitored did not truant. Similar patterns of weak association were also apparent for SES and attitudes to teachers and school. These relatively weak associations were in marked contrast to the associations of truancy with later education and employment outcomes. Truancy was a very strong predictor of negative outcomes but background factors associated with truancy were much less good predictors of truanting behaviour.

In the present paper, we use the data from another large-scale panel survey, the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE) to extend our previous analysis in a number of ways. First of all, it enables us to replicate the analysis using a much larger sample size than was available for the BHPS. As well as being a replication it also allows some analyses which were not possible in the earlier paper because the relatively limited sample meant that there were too few young people in certain categories, for example, persistent truants from high SES backgrounds. It is also possible to conduct a more extended analysis of the relation of truancy to academic attainment as the LSYPE data-set can be linked to the National Pupil Database. It should be noted that although we are describing the study as a replication, the way that truancy questions were asked differed slightly across the two studies. However, in both studies, self-reports of truancy could be placed in three categories: none, low level and high level. Obviously, the none category is identical across the studies. But in the earlier study, the low level was a response of “once or twice” and the high category “several times” or “often” to a question about truancy in the previous year. In the current study, the low category was a response of “particular lessons” or “just the odd day or lesson” and the high category a response of “several days at a time” or “weeks at a time”.

A further focus of the current study which was not present in the earlier analysis is that of pupil well-being and its relationship to truancy. A concern with well-being and with personal happiness, both among children and in the population more generally, has informed a variety of policy initiatives and academic studies. The government Green Paper, Every Child Matters (Department for Education 2003) drew attention to a wide range of problems associated with childhood and stressed the role of schools in promoting well-being. Recently, the Department for Education supported an initiative in three local authorities using an intervention to improve young people’s resilience and mental health. This had mixed results and limited long-term impact (Department for Education 2011a). The concern with well-being has been informed by the results of a UNICEF (2007) study which suggested that children in the UK had the lowest levels of personal well-being of 20 advanced societies in the OECD. Further evidence comes from a recent academic study of well-being and young people which refers to the, “… widespread perception that the social and emotional well-being of young people has been in decline …” (Gray et al. 2011, 1). There has been a growth of interest in and studies of subjective measures of happiness and personal satisfaction both in populations generally and specifically in young people, especially associated with the work of the economist Richard Layard. Layard points to the paradox that, “… as Western societies have got richer, their people have become no happier.” (2006, 3) and argues for the importance of studying happiness and well-being alongside other more conventional social and economic indicators. The LSYPE data-set includes measures of young people’s subjective feelings about themselves which give an indication of mental well-being as described below. These measures make it possible to consider truancy in a wider context of a more general sense of well-being, alongside the other social and educational factors we have described.

Methods: the LSYPE data-set

The research reported here is based on a secondary analysis of the LSYPE (Department for Education 2011b). This is a large-scale government-funded panel survey of young people and their families. The aim of the survey was to support the development and evaluation of education policy, in particular, policies concerned with the transition from education to employment. The survey began in 2004, when the young people were 13/14 and has been repeated every year up to 2010. Information was gathered by means of face-to-face personal interviews which included self-completion of some sensitive items. In addition to the young person’s interview, the parent identified as the parent most concerned with the young person’s education and designated as the “main parent” was interviewed. In most cases, a “second parent” was also interviewed. Data were collected on the socio-economic and educational background of parents, on many aspects of the attitudes, behaviour and educational intentions of the young person and information was also collected about the school they attended. Young people were sampled through their schools in both the maintained and independent sector. The final sample was of approximately 21,000 young people born between September 1989 and August 1990 and 15,770 of these were successfully interviewed in Wave 1, a response rate of 74%. As with all longitudinal surveys, cumulative attrition means that the final response rate is lower than that at any particular wave and the 8682 Wave-7 interviews represented just 41% of the original sample of 21,000. Weights have been calculated for the sample at each wave to allow for the survey design and for survey attrition. This means that the demographic characteristics of sample used for the analysis, for example, the proportion in different socio-economic categories, is identical across the various waves. The data used in this article come from the young people interviewed at both Wave 2 and Wave 7. LSYPE data can be linked to administrative data such as the National Pupil Database. This means that robust attainment data in NPD can be used in an analysis along with family background data and data on young people’s own perspectives and intentions.

The analysis for this paper uses data collected at Wave 2 of the survey when the young people were 14 or 15 and Wave 7 of the survey when they were 20 or 21. Key variables are their answer to the question of whether they had truanted in the last year and, if so, how frequently and for what reasons. The young people were also asked a variety of questions about school: how much they valued school, how they got on with their teachers and whether they had been bullied. Data on parental occupations come from the parent interviews at Wave 2 and these have been used for the classification of socio-economic background. Information on levels of educational attainment come from National Pupil Database. Attainment measures used in this paper are the GCSE examination taken when the young people were aged about 16 and the Key Stage-2 assessments at the age of 11. The Wave-7 interviews, when the young people were aged about 20, provide measures of outcomes such as educational attainment and participation, employment and life satisfaction which can be related to the earlier Wave-2 data.

Wave 2 of the survey also included the 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), a widely used measure of mental well-being which was discussed earlier. The GHQ was developed by Goldberg and colleagues as a measure of current mental health (Goldberg and Hillier 1979). Despite its title, it is specifically concerned with psychological well-being rather than health more generally and asks people to describe their ability to carry out normal functions and the extent of distressing experiences. Items include self-descriptions of concentration, worry, strain, decision-making and so on. The items used in the present study are listed in Table 5. The original scale consisted of 60 items and there are 30-item, 28-item and 12-item versions. All versions of the scale have high levels of reliability and have been widely validated (Goldberg and Huxley 1980) including validation for use with young people (Banks 1983).

Results

Self-reported truancy: extent and motivation

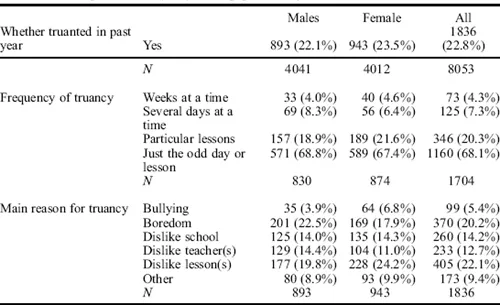

The young people were asked whether they had played truant in the past year and, if so, how frequently and for what reason. The results of these questions are presented in Table 1 for all pupils and separately for males and females. As the figures in Table 1 show, some degree of truancy was widespread in year 10. Between a fifth and a quarter of the young people said that they had truanted with males and females having very similar levels. However, most of this truanting behaviour was fairly limited. Two-thirds of truants said that their truancy was limited to the odd day or lesson and another fifth said it was limited to particular lessons. These two categories accounted for almost nine-tenths of truanting behaviour. More serious truancy was limited to just over 10% of truants: 7.3% said their truancy involved several days at a time and 4.3% said that it involved weeks at a time. This means that for the whole sample, just two-and-a-half per cent reported truanting for more than the odd day or lesson and the most serious truancy, involving weeks, was limited to just under 1% of the sample. As with truancy overall, there were no gender differences with regard to the more extreme end of truancy.

Table 1. Self-reported truancy in year-10 pupils in England.

The main reasons the young people gave for their truanting behaviour are also presented in Table 1. Nearly all of the young people, about 90%, gave a reason to explain their behaviour. For half of the young people, the reason was a specific dislike of some aspect of schools, teachers or lessons. The most common response was a dislike of a lesson or lessons (22.1%), followed by a general dislike of school (14.2%) and a dislike of a teacher or teachers (12.7%). A further 20.2% said that they truanted because they were bored, and about 70% of the sample identified some aspect of school that they disliked or that bored them as a reason for missing school. However, a specific dislike of a teacher or teachers was less common than a dislike of a lesson or lessons or school more generally. Only about one in twenty of th...