![]()

INTRODUCTION

Postcolonial literature and challenges for the new millennium

This special issue is concerned with readings of literary texts that reposition and reinvigorate postcolonial studies in the twenty-first century. If, after 9/11, the war against terror dominates geopolitical paradigms in our post-millennial age, then it has also engendered polarized global ideologies operating both within and beyond the state. Democracy – variously congruent with concerns spanning neo-liberal economics to nuclear proliferation to freedom of speech to Third World feminism – is thus variously pitted against the purported pitfalls of authoritarianism, fundamentalism, and totalitarianism. Postcolonial studies – with its vested theoretical engagement with the uneven effects of globalization’s vicissitudes alongside a commitment to the continued intimacies with colonization – is propitiously placed to offer a critical role in this new world order.

Each of the critical essays covered in this special issue is refracted through one of four broad concerns at the frontlines of the political landscape of the twenty-first century: war, fundamentalism, ecology, and Chinese authoritarianism. But while this issue aims primarily to evince the nexus between literary aesthetics and representations of these political concerns in individual texts, it also attempts to suggest, at least in the contributors’ collective efforts, that these political sites are also imbricated in each other. The essays collected in this volume thus share the recognition that postcolonial studies is in the process of addressing the political transformations made explicitly visible in the twenty-first century: major shifts in the global arena of political (and economic) power, different forms of neocolonialism, the rhetoric, nature, and scars of long-term civil wars, newer forms of epistemological violence linked to territorial dispossession, and an increasing awareness of a future indelibly marked by environmental destruction.

In acknowledgement of the growing recognition that global power is shifting to the East, this special issue opens with two essays which consider forms of political resistance to the Chinese state by two Chinese writers exiled in Europe – Bei Dao and Ma Jian. Bill Ashcroft’s and Lucienne Loh’s essays seek to position contemporary Chinese literature within new postcolonial paradigms. That China previously participated in national liberation movements from the 1960s onwards, but has now turned into a champion for a sino-centric national essentialism legitimized by networks of global capital and instituted through totalitarianism, implies the failure of the utopian hopes underpinning previous notions of postcolonial solidarity. However, with China’s increasing global economic reach, widening spheres of geopolitical influence, and seemingly unending quest for natural resources, to what extent can we consider China to have overtaken the USA as today’s foremost neoimperial power?

While Chinese writers in exile frequently promote democratic ideologies through their literature to combat the brutal suppression of free expression in China, these ideologies themselves are thoroughly questioned in the essays by Robert Spencer and Anshuman Mondal, both of which focus on the ethnical contradictions and hypocrisies involved in postcolonial literature’s attempts to contest Islamism through secular, and purportedly democratic, narratives. Through a close reading of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, Mondal’s essay offers a radical new re-reading of the fatwa controversy and asserts that the unequivocal secular orthodoxies within Rushdie’s novel underwrite it as ‘an extraordinary act of bad faith’, while replicating precisely the fundamentalism it opposes. Spencer’s essay, too, shares Mondal’s argument that fundamentalism is less about religious belief and more about a dogmatic refusal to accept any form of self-interrogation. An example of the latter, Spencer suggests, is Azar Nafisi’s much feted memoir, Reading Lolita in Tehran, an uncritical celebration of Western ‘civilization’. Instead, he chooses to read Yasmina Khadra’s The Attack (L’attentat) as an example of a novel which self-consciously disputes and complicates the simplistic ideological binaries which have arisen around twenty-first-century discourses on terror and fundamentalism.

Similarly concerned with these political discourses, Oona Frawley’s essay on Nadeem Aslam’s The Wasted Vigil provocatively suggests that the contemporary discourse of extremism and a legacy of colonialism have complicated the ways in which we understand and define civil wars. She argues that Aslam refuses to conform to a template of the ‘immigrant novel’ by setting The Wasted Vigil in Afghanistan, ‘one of the most overwritten geographical spaces on earth’, where historical and cultural identities (just like our definitions of civil war) are consistently changing. While the concept of civil war, in modern representations, often seems coloured by a presumption of being a Southern phenomenon and problem, Aslam’s Anglophone novel encapsulates the global trajectories of such conflicts which helps reimagine America’s current occupation of Afghanistan in critically important ways. The twentieth century was defined by successive large-scale and long-term wars and saw the invention of some of the deadliest weapons of mass murder in the history of humanity which culminates in the current order of a global war on terror with unlimited geographical reach. If such a war also seems interminable then it is a reminder that systemic violence, of the kind invented in the last century, is never a historically bounded occurrence. This is especially true where residues of modern warfare and unexploded armaments prolong the environmental effects and multiply the human casualties of wars. Andrew Mahlstedt’s energetic reading of Mia Couto’s The Last Flight of the Flamingo engages with a conceptualization of residue, a Mozambican landscape embedded with landmines, which is in itself of inherent value to understand the effects of a long history of exploitation including 30 years of civil war following decolonization.

Analyses of texts such as Aslam’s and Couto’s critically point towards strategic reading practices. Malcolm Sen’s essay, alternatively, discusses the representational tactics adopted by authors such as Romesh Gunesekara to represent violence with not only human but also environmental casualties. Gunesekara’s novel Reef, Sen suggests, is a key text which imaginatively envisions changes in Sri Lanka’s natural environment to describe the unseen and slow process of maritime ruination that serves as a complex allegory of the political turmoil on land. Undermining romantic idealizations of the colonial landscape thus remains a preoccupation of postcolonial writers. In Jill Didur’s reading of Anita Desai’s Fire on the Mountain, she strategically reveals the anti-picturesque underbelly of the socio-political constructions of colonial hill stations in India. Didur’s archival material related to the rabies testing centre at the Pasteur Institute in Kasauli, in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh, is strikingly rich in its subversive potential which undermines, disrupts, and dislocates the popular picturesque descriptions of colonial hill stations as environmental retreats. Reflecting on the above essays, Neil Lazarus ends this special issue with a provocative epilogue which reasserts the crucial role of world literature within the politics of postcolonial studies today.

Lucienne Loh

University of Liverpool

Malcolm Sen

University of Notre Dame

![]()

Bill Ashcroft

Including China: Bei Dao, resistance and the imperial state

This article suggest how we might include China in postcolonial studies. Despite its lingering sense of victimization by the West, China’s peculiar manifestation of continental imperial power upon its 55 ethnic cultures makes it amenable to a post-colonial reading. But the case of the Bei Dao and the ‘misty poets’ shows how imperial power is threatened by a form of literary resistance, developed through a new language and an annoyingly obscure literary form, that exists outside state control. The relevance of a post-colonial reading can be seen in the development of a ‘new’ literary language, drawing on the style of ancient Chinese poetry, the ambiguously empowering experience of exile and the persistence of a utopian hope for the future.

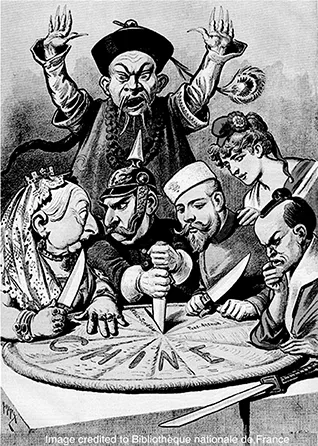

How do we include China in post-colonial studies? China has regarded itself, at least since the Opium wars of 1829 and 1856 and the humiliating Treaties of Nanjing (1842) and Tientsin (1858) as being victimized and colonized by the West and Japan. Towards the end of the nineteenth-century China seemed to be on the way to territorial dismemberment between Britain, Germany, Russia, France, and Japan, as a cartoon from Le Petit Journal, 16 January 1898 indicates.

Several regions of China, most notably Shanghai (along with over 80 other Treaty Ports), were colonized by these powers, which helps explain the long-standing feeling of victimhood nursed by Chinese ruling elites. Yet, since the Qing dynasty of 1642, China itself has been a constantly expanding Empire, and from the middle of the twentieth century, it is clear that China, both Maoist and post-Maoist, has been an Empire parading as a nation.1 Whether communist dictatorship under Mao (1949–1976) or centrally planned capitalist economy (under Deng Xiaoping 1978–1992 and his successors), China has been ruled by an imperial oligarchy, subsuming regional and ethnic minorities under the mantle of one nation, one language, one system, all in the interests of ‘social harmony’ – a euphemism for unquestioned obedience to the state. Its territorial expansion limited to countries on its borders, China’s imperialism has been, historically, a continental one characterized by absorption rather than overt colonization, although to its non-Han ethnic minorities, colonization is the result in fact if not in name.

It is this peculiar manifestation of continental imperial power upon its many ethnic cultures that makes China amenable to a post-colonial reading. China is imperialist not only in its expansionist policy, its desire to absorb non-Han minorities, its desire to compete with America along the lines of imperial power (whether ‘soft’ or ‘hard’), but crucially, it is imperialist in its totalitarian attitude to dissent and in its management of national history and public consciousness. In this sense, it functions like the colonial state that quashed the Mau-Mau resistance in Kenya in the 1950s and is in some ways, akin to the apartheid South African post-colonial state. In both these instances, writers played a crucial role in creating dissent; the literature and language become crucial modes for that dissent.

A post-colonial reading may not be limited to the cultural productions of those minority cultures overrun and colonized by the state but to various productions resistant to the ‘imperial’ control of communist rule. The identification of post-colonialism as a reading practice is crucial here. ‘Post-colonial’ is neither a chronological nor an ontological term. Colonial power does not cease after independence and there is no inclusive ‘post-colonial condition’. Rather post-colonial experience and post-colonial cultural production are read in a post-colonial way. Post-colonial is itself a term for a particular way of reading. Post-colonial reading has itself broadened its scope to include strategies to address the contemporary global world. As Simon Gikandi points out, the language of post-colonial studies came to dominate globalization theory in the 1990s. Varied as the two discourses might be

… they have at least two important things in common: they are concerned with explaining forms of social and cultural organization whose ambition is to transcend the boundaries of the nation-state, and they seek to provide new vistas for understanding cultural flows that can no longer be explained by a homogenous Eurocentric narrative of development and social change.2

Clearly, the ‘cultural turn’ in globalization studies in the 1990s and the influence of a post-colonial inspired language in that ‘turn’ meant that ‘post-colonial’ could now be used to refer to diverse forms of cultural production, often rendering the term so diffuse and endlessly employable as to be virtually useless. We, therefore, need to be very careful about blurring the character of post-colonial analysis. Its brief is still to investigate and analyze the engagement of colonized and formerly colonized people with imperial power and it...