![]()

Sin Kiong Wonga, Ruixin Wangb, Zhuo Wangb and Shihlun Allen Chenc

aDepartment of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore, Singapore; bIndependent Researcher; cCultural Anthropology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA

In Singapore, intellectuals, especially those in media and education, are considered as the driving force of formatting public opinion over the social imagination of China and Chineseness. This article, largely based on oral histories of some Singaporean scholars and media professionals and memoirs of related figures, analyzes the choice and acquisition of their knowledge on China. Through the analysis and comparison of their construction of knowledge on China, this article also discusses the accuracy of their understanding of China and how such understandings were formed along with their personal experiences from domestic socialization, education, and professional accumulation. The authors consequently map out the process of how public intellectuals from mass media and academia transform their knowledge imagination of China into the professional opinions that help to reconstruct and shift Singaporean’s impression and understandings of China.

1. Introduction

Because of Singapore’s geographical location, historical development, and social structure, the development and understanding of the knowledge on China in the intellectual community in Singapore is unique. Singapore is a nation located on a small island in Southeast Asia, which had been under British rule for a long time before independence in 1965. Since the mid-nineteenth century, a large number of Chinese immigrants have moved in making Chinese the largest ethnic group in Singapore. Singapore also has a Malay community, Indian community, and Eurasian community, so it is therefore a multi-ethnic and multicultural country and society. Even within the Chinese community, due to the differences in period of migration, generation, family and educational background, social class and occupation, knowledge and understanding of China vary. Since academia1 and mass media2 have relatively large awareness and influence over knowledge on China, this article therefore relies mainly on the intellectuals in these two fields. This article, based on oral histories of some Singaporean scholars and media professionals and memoirs of related figures, analyzes the choice and acquisition of their knowledge on China. Also, through the analysis and comparison of Singapore’s academia and media’s construction of knowledge on China, this article discusses the accuracy of their understanding of China.

2. The choice and acquisition of knowledge on China of Singapore’s academia

Singaporean academics refer to those people in universities of Singapore who engage in research and teaching. For the purpose of this article, focus will be on those who teach and conduct research on China. Because of their strong professional and educational influences, their influence of the construction of Singapore’s China study has been significant. Yet, it is worth exploring the question how do they acquire their knowledge on China?

According to our interviews with them, their ways of contacting and acquiring knowledge on China came from four aspects: First, and the most direct way, is their education from Chinese language

3 institutions. For the six interviewed scholars, they have one trait in common, which is that they all received formal Chinese education. Chew Cheng Hai, for example, attended Junyuan Primary School, which is a missionary school using the Chinese language as medium of instruction. Then he entered the Yuying Secondary School, which was established by Hainanese. He even learned a lot of the Hainan dialect at that time. However, his Chinese knowledge was established fully and systematically during the 4 years of study at Nanyang University’s Chinese Department. In the early 1950s, when Nanyang University was established, it was the only Chinese University outside of China. Because the remuneration

4 was very good during the early days, it attracted many renowned scholars from Taiwan, who had migrated from mainland China during the final years of China’s civil war in the late 1940s, to come to teach at the university. Therefore, the quality of teachers was strong. For example, Chew Cheng Hai’s study of paleography was taught by Li Xiaoding (

), who was a research fellow of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, and a professor of Chinese literature at National Taiwan University before he came to Singapore. Pan Zhonggui (

), who is known in his study of

Dream of the Red Chamber and later became the Head of the Chinese department and the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts of New Asia College, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, also taught at Nanyang University at that time. It was this group of teachers that lead Chew Cheng Hai into the field of Chinese studies.

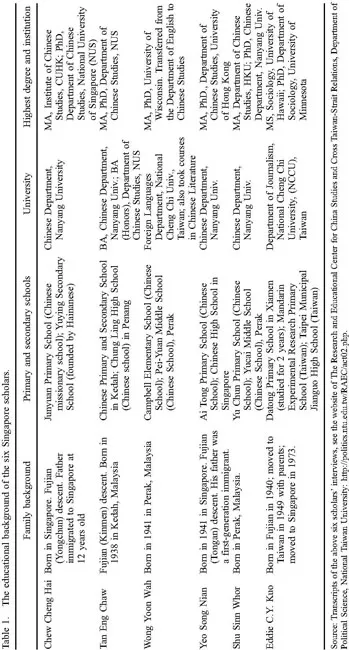

In addition to Chew Cheng Hai, all the other scholars, who were chosen in this article as research subjects, are Chinese educated. Their educational background is given in Table 1.

The six scholars had different backgrounds in their early lives as shown in Table 1, but they all studied at Chinese schools in their primary and secondary education. In Chinese schools, they built a sound foundation in Chinese language and also cultivated within them an identity of ‘I am Chinese.’ Among them, there are four scholars who graduated from the Department of Chinese at Nanyang University, which was the only Chinese university in Southeast Asia at the time. The other two scholars had their university education in Taiwan. The choice of Chinese education from primary school through secondary school opened the first gate of knowledge on China for these scholars and laid the foundation for their continuing studies of China. Their tertiary education was a critical stage of gradual improvement and consolidation of their knowledge on China. For example, during their university years, Chew Cheng Hai discovered his interest in ancient philology, while Yeo Song Nian developed a preference for Chinese literature, Tan Eng Chaw had special research interest in Chinese history, and Shu Sinn Whor became particularly interested in the study of Confucianism. Thus, Chinese school education is indeed an important choice and channel for accessing and obtaining knowledge on China among academics in Singapore.

At different stages of obtaining knowledge on China, there are differences in the contents, condition, and accuracy. The period of primary and secondary education is the stage of gaining basic knowledge on China and learning the language. Its accuracy depends on the teachers’ knowledge and teaching quality. For example, as in the mid-twentieth century, some Chinese teachers might be more comfortable in speaking local dialects than Mandarin, the accuracy of language learning would be greatly reduced. The advanced knowledge on China and the further study of Chinese language, culture, history, and other aspects of knowledge on China took place during the peri...