![]()

Is there an entrepreneurial culture? A review of empirical research

James C. Hayton and Gabriella Cacciotti

Warwick Business School, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK

The literature on the association between cultural values and entrepreneurial beliefs, motives and behaviours has grown significantly over the last decade. Through its influence on beliefs, motives and behaviours, culture can magnify or mitigate the impact of institutional and economic conditions upon entrepreneurial activity. Understanding the impact of national culture, alone and in interaction with other contextual factors, is important for refining our knowledge of how entrepreneurs think and act. We present a review of the literature with the goal of distilling the major findings, points of consensus and points of disagreement, as well as identify major gaps. Research has advanced significantly with respect to examining complex interactions among cultural, economic and institutional factors. As a result, a more complex and nuanced view of culture’s consequences is slowly emerging. However, work that connects culture to individual motives, beliefs and values has not built significantly upon earlier work on entrepreneurial cognition. Evidence for the mediating processes linking culture and behaviour remains sparse and inconsistent, often dogged by methodological challenges. Our review suggests that we can be less confident, rather than more, in the existence of a single entrepreneurial culture. We conclude with suggestions for future research.

1. Introduction

One of the oldest research questions in the field of entrepreneurship is how and to what extent does national culture influence entrepreneurial action, the rate of new firm formation and ultimately economic development (e.g. McClelland 1961; Weber 1930; Schumpeter 1934)? It has long been established that the level of entrepreneurial activity varies across countries and regions and this variation has been associated with both economic and social benefits (e.g. Audretsch and Thurik 2001; Birley 1987; van Praag and Versloot 2007; van Stel 2005; Wennekers, Uhlaner, and Thurik 2002). As with many topics in an applied field, scholars from diverse disciplinary backgrounds have addressed this question (Hayton, George, and Zahra 2002). However, often such disciplinary diversity can lead to challenges with respect to the incremental development of a knowledge base as scholars emphasize different theoretical lenses, languages, research questions and methods. In particular, the recent expansion in published empirical research on this topic raises the question of whether the convergence observed by Hayton, George, and Zahra (2002) towards a single view of entrepreneurial culture continues to be tenable. In contrast, does recent research create a more nuanced, but less consistent story about what aspects of culture support entrepreneurial decision and action? Understanding the real impact of culture, and the ways in which culture may moderate, or be mitigated by contextual factors such as institutions and economic development, has great significance for theorizing about, and empirically studying entrepreneurial behaviour around the world. It is also of importance for policy-makers concerned with promoting entrepreneurial activity. It is from this perspective that it is of value to review, organize and evaluate what we now know.

Hofstede (2001, 9) described culture as a ‘collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another.’ We therefore define culture as the values, beliefs and expected behaviours that are sufficiently common across people within (or from) a given geographic region as to be considered as shared (e.g. Herbig 1994; Hofstede 1980). To the extent that cultural values lead to an acceptance of uncertainty and risk taking, they are expected to be supportive of the creativity and innovation underlying entrepreneurial action. Entrepreneurial actions are facilitated both by formal institutions (e.g. property rights, enforceable contracts) and by socially shared beliefs and values that reward or inhibit the necessary behaviours (e.g. innovation, creativity, risk taking; Hayton, George, and Zahra 2002; Herbig and Miller 1992; Herbig 1994; Hofstede 1980). It is because of this subtle but widespread influence of culture that it is necessary to seek a deeper understanding of the phenomenon. For the purposes of this review, we assume a broad definition of entrepreneurship that includes growth oriented new-venture creation, but also extends to small and micro-enterprises that do not typically lead to employment growth beyond self-employment (Bhide 2000).

We take as a starting point the review by Hayton, George, and Zahra (2002), which offered a review of behavioural research into ‘culture’s consequences’ for entrepreneurship, to borrow from Hofstede’s famous title (Hofstede 1980). We focus on empirical research in order to get an accurate gauge on what we now know, and particularly what we have learned over the past decade of research. To identify articles for inclusion, we searched the ABI-Inform and Business Source Premier databases for references to national culture and entrepreneurship. These databases include extensive collections of journals that most frequently publish entrepreneurship and cross-cultural behavioural research (e.g. Journal of Business Venturing, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, Journal of International Business Studies, Academy of Management Journal and Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal). We also examined the reference lists of all studies found through our search to identify articles not discovered through a search of the databases. We have only included single or multi-country studies that address the significance of culture, however defined or operationalized, for entrepreneurship. In all, seven studies have been excluded on the grounds that they do not measure national culture, but only infer it from country (Uhlaner and Thurik 2007; Freytag and Thurik 2007; Beugelsdijk 2007; Beugelsdijk and Noorderhaven 2004; Swierczek and Quang 2004; Stewart et al. 2003; De Pillis and Reardon 2007). In addition to the 21 empirical studies already identified in Hayton, George, and Zahra (2002), we found an additional 21 empirical studies published from 2001 to 2012.

Our review of the recent research on culture and entrepreneurship revealed research streams previously identified by Hayton, George, and Zahra (2002).1 Rather than proposing a new analytical framework, we preferred to examine the research questions, methods and results of the studies in those research streams for two reasons: this organization of the research is still appropriate; and it allows us to directly evaluate the extent to which knowledge has been updated over the past decade, and areas where research is still needed. The first research stream addresses the impact of national culture on rates of innovation and entrepreneurship at the national or regional level. The second stream focuses on the relationship between culture and the beliefs, motives, values and cognitions of entrepreneurs across regional and national boundaries. This second stream is itself divided into two parts. The first presents evidence for differences across regions or countries in terms of the individual beliefs, motives and values associated with entrepreneurial behaviour. The second focuses on the existence of an entrepreneurial mindset, and reflects a test of the ‘deviance’ hypothesis – i.e. that by necessity, entrepreneurs somehow deviate from cultural norms. At the end of our review of each of these streams of research, we offer a summary that provides a critical evaluation of the state of the art with respect to culture’s consequences. In the last sections of the paper, we revise the model of national culture and entrepreneurship suggested by Hayton, George, and Zahra (2002), and conclude by offering suggestions for future research.

2. National culture and entrepreneurship at the national or regional level

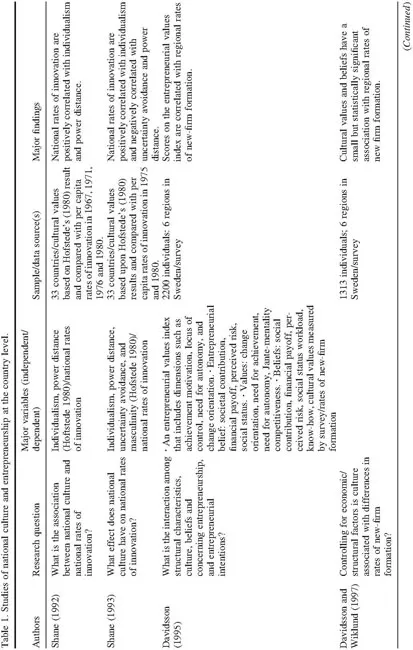

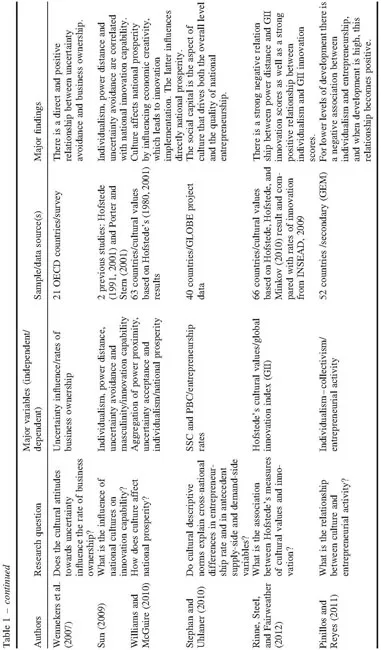

A growing number of studies have addressed the relationship between national or regional culture and aggregate levels of entrepreneurship (Davidsson 1995; Davidsson and Wiklund 1997; Rinne, Steel, and Fairweather 2012; Shane 1992, 1993; Stephan and Uhlaner 2010; Sun 2009; Williams and McGuire 2010). These studies are summarized in Table 1.

2.1. Culture and national rates of innovation

We can subdivide studies at the national level based upon the operationalization of the dependent variable. Several studies have examined the relationship between culture and aggregate rates of innovation (Shane 1992, 1993; Sun 2009; Rinne, Steel, and Fairweather 2012; Williams and McGuire 2010). Shane’s (1992, 1993) studies provided preliminary evidence that Hofstede’s cultural dimensions of individualism, power distance and uncertainty avoidance were significantly associated with national rates of innovation, after controlling for national wealth. However, Shane (1993) reported that the association between individualism, power distance and innovation rates was not stable over time. Sun (2009) and Rinne, Steel, and Fairweather (2012) offer mixed support for Shane’s (1992, 1993) by using different sources for innovation rates (Porter and Stern 2001; INSEAD 2009). While both studies also suggest an association between individualism, power distance and innovation capability, they only examine a single time period, and do not control for other potential confounding factors such as GDP or stage of economic development.

In contrast with previous studies, Williams and McGuire reframed Hofstede’s culture variables and created an aggregate measure of culture to examine its relationship with innovation at national level. They propose that ‘culture is a multidimensional phenomenon whose constituent parts interact to create the whole’ (2010, 393) and the diverse aspects of culture should be taken together in order to measure the effect of culture at national level of analysis. Therefore, in this study culture is treated as a single latent variable reflecting three dimensions: power proximity, uncertainty acceptance and individualism. They found that when national culture was operationalized in this way, these combined dimensions were positively associated with economic creativity, and indirectly with innovation.

2.2. Culture and new firm formation

Following the early empirical research by Davidsson (1995) and Davidsson and Wiklund (1997), three studies have explored the relationship between national culture and entrepreneurial activity in the last decade (Stephan and Uhlaner 2010; Wennekers et al. 2007; Pinillos and Reyes 2011). In these studies, entrepreneurial activity was operationalized as new firm formation or firm ownership rates.

Wennekers et al. (2007) examined the relationship between uncertainty avoidance and variation in business ownership rates across countries. Using data from a sample of 21 countries in 1976, 1990 and 2004, Wennekers et al.’s (2007) results showed that, contrary to prior evidence, high uncertainty avoidance could actually push individuals towards self-employment. Their hypotheses rest on the proposition that in uncertainty avoiding countries, entrepreneurship is the route through which innovators may pursue their objectives, while in less restrictive environments, entrepreneurial individuals may be able to pursue their goals within the context of employment. However, they found that this relationship was not stable over time. In addition, the authors report a negative moderating influence of uncertainty avoidance on the relationship between GDP per capita and business ownership: the effect of GDP on entrepreneurship rates is observed to be smaller in low-uncertainty avoidance countries than in high-uncertainty avoidance countries. This study provides evidence that the role of uncertainty avoidance is complex and may not be reducible to a simple, linear association.

Pinillos and Reyes (2011) also questioned the assumption of a simple linear association between culture and entrepreneurial activity. They observed that despite arguments that individualism is positively associated with entrepreneurship, there are many countries characterized by collectivist orientation which also exhibit high levels of entrepreneurial activity. Using data from the global entrepreneurship monitor project, these authors showed that for lower levels of development, there was a negative association between individualism and entrepreneurship, and when development was high, this relationship became positive.

A study by Stephan and Uhlaner (2010) also contradicts the established view on individualistic cultures being supportive of entrepreneurship. They used descriptive norms rather than cultural values to predict variations in cross-national entrepreneurship. According to the values approach, culture is measured as the aggregation of individual scores of values and preferences. In contrast, descriptive norms are measured by asking respondents to describe characteristic behaviours displayed by most people within their culture. Only if there is adequate evidence for agreement, are they then aggregated to a higher level of regional or national cultural values. Thus a values-based approach reflects a more direct measure, but depends upon the representativeness of the sample. The descriptive norms approach is an indirect measure, but depends upon the knowledge that respondents possess of the typical behaviours. Based on data from the GLOBE project, Stephan and Uhlaner (2010) identified two higher order factors: performance-based culture (PBC) and socially supportive culture (SSC). The first factor, PBC, is described by Stephan and Uhlaner (2010, 1351) as ‘a culture that rewards individual accomplishments as opposed to ...