![]()

The elegant plume: ostrich feathers, African commercial networks, and European capitalism

Aomar Bouma and Michael Bonineb†

aDepartment of Anthropology, UCLA, CA, USA; bSchool of Middle Eastern and North African Studies, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA

Ostrich feathers have long been an important export from Africa to different European markets. The ostrich plume was a key part of the luxury trade across Mediterranean shores for centuries. The main source of ostrich feathers was from wild ostriches especially from North and West Africa. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the rising economic value of ostrich plumes triggered colonial French and British competition over this luxury commodity, leading to the establishment of domesticated ostrich farms by the French in North and West Africa and by the British in South Africa. This article uses an economic historical framework to understand colonial ostrich feather trade and its impact on French and British relations during the nineteenth century in Africa. We examine the ostrich feather commercial networks that began to emerge particularly by the middle of nineteenth century, and focus on the sources of ostrich feathers and the local practices for hunting and raising ostriches. We argue that by looking at the need for ostrich plumes in European markets and the rise in public consumption of fashion goods based on the ostrich plume, nineteenth-century European capitalism destroyed not only the wild African ostriches, but also local African livelihoods based on wild ostriches.

The ostrich plume has had an important symbolic significance in the Old World since antiquity, as well as being important among numerous non-literate tribes in Africa and the Middle East for millennia. This elegant feather was often the symbol of authority, power, and prestige among the royalty of the ancient Near East and was also adopted by the monarchs and their courts in Europe. Warriors and rulers in ancient times might have had a single plume or perhaps an elaborate headdress, or an ostrich fan or ostrich feathers on a staff. The ceremonial display of headdresses and emblems that contained ostrich feathers were part of many cultures. First in Europe, and then in the United States, as of the seventeenth century, the ostrich plume became more common and fashionable, although it remained an expensive elite luxury item. By the last half of the nineteenth century, however, the display of ostrich feathers expanded considerably (in size and clientele), as plumes of ostriches and other birds became the fashion among the well-to-do women of Europe and America, both for elaborate hats with long plumes as well as ostrich fans, boas, stoles, muffs, and pompoms (Figure 1).

In the twenty-first century, many African farmers have benefited from the rising price of ostrich meat and feathers outside the continent. Europe and North America have renewed their historical interest in the African ostrich (Gillespie et al. 1998). South African ostrich meat is today the driving force rather than feathers, as it had been in the nineteenth century.

An online website describes this phenomenon:

European confidence in red meat products plummets after successive health scares. Ostrich meat has the color and consistency of beef but provides a healthy red-meat alternative, being low in fat and cholesterol. The price of ostrich carcasses has risen by 25% in recent months.1

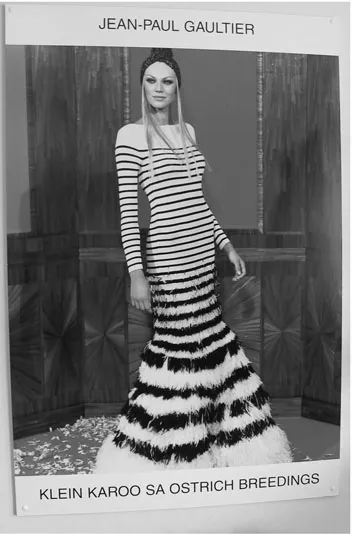

The fashion industry is also rediscovering the ostrich feather (Nixon 2001). Recently a Gucci advertisement read: ‘Wear the ostrich feather with pride again’.2 In Paris, New York, Los Angeles, London, and other global fashion capitals, ostrich feathers are used for fashion accessories such as evening wear, hats, and even wedding dresses. In 2002, ostrich accessories were presented at a fashion show in Paris attended by the famous fashion designer Pierre Cardin. The fashion for ostrich feathers is also evident in Rio de Janeiro’s annual Carnival where dancers wear entire outfits of ostrich feathers, mostly imported from South African farms. Although the ostrich feather market has not yet regained its former historical success, from the rising export numbers and increasing ostrich farming, it appears that Europe and the Americas are again falling in love with Africa’s ostriches (Williams 2012) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Postcard of Queen Mary wearing a hat with ostrich feathers (Courtesy Michael Bonine).

Figure 2. An advertisement of a Jean-Paul Gaultier ostrich dress in Klein Karoo Cooperative, Oudtshoorn, South Africa (Courtesy Michael Bonine, 2008).

Ostrich eggs (Green 2006) and feathers (Stein 2008) have also been an important export from North Africa to European markets (Schroeter 1988). As commodities, they were part of the valuable luxury trade crossing the southern shores of the Mediterranean as far back as the Roman, Assyrian, and Babylonian empires (Lefèvre 1914). Until the late nineteenth century, the source of feathers was principally from wild ostriches hunted in Syria (Mosenthal and Harting 1877, 236), the Arabian Peninsula, and North and West Africa (Table 1). Table 1 summarises the origins and characteristics of African ostriches during 1875. Of note is that by the 1870s, South African merchants were starting to redirect world exports of ostrich feathers from the traditional North African ports (Mogador, Tripoli, and Cairo) towards Cape Town. The historical value of ostrich plumes triggered a colonial French and British competition leading to attempts to establish domesticated ostrich farms (Daumas 1971, 61), by the French in North and West Africa and the British in South Africa; an industry that soon spread to a number of other countries, such as Australia in 1873, Argentina in 1880 (Douglass 1881, 4), and the USA in 1883 (Duncan 1888, 686).

Table 1. Ostrich feathers brands, origin, qualities, and values in 1875a

| Feather brand | Origin and characteristics | Exports (£) |

| Aleppo | Syrian desert; most perfect in feather quality, breadth, grace, and colour; very rare | ? |

| Barbary | Tripoli | 100,000 |

| Senegal | Saint Louis | 3000 |

| Egypt | Good colour; do not bleach | 350,000 |

| Mogador | Morocco | 20,000 |

| Cape | Good colour; inferior quality | 230,000 |

| Yemen | Arabia; commonly but erroneously designated ‘Senegal’; inferior in feather quality, thin, and poor | ? |

aQuoted in Mosenthal and Harting (1877, 224–225).

In her work on ostrich feathers, Stein looks at the key role of Jews in the global trade of this commodity. She explores the way Jews

fostered and nurtured the supply side of the global ostrich feather industry at all levels and stages – from feather handler to financier and from bird to bonnet – and over the varied geographical and political terrains in which the plumes were grown, plucked, sorted, exported, imported, auctioned, wholesaled, and manufactured for sale. (2008, 26)

We take a different perspective without overlooking the importance of the Jewish role in our historical narrative. Our focus is not only on the relationship between the bird’s consumption and the feather fashion, but also on the larger economic and environmental consequences of European interest in this luxury item, and its impact, from an environmental economic perspective, on North Africa and sub-Saharan African tribal societies.

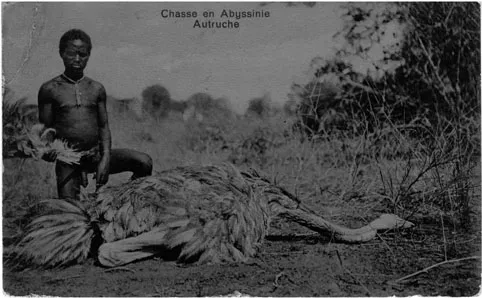

We examine in particular the feather trade that had developed by the late nineteenth century, focusing on the sources of feathers and the local practices for hunting and raising ostriches. We contend that by looking at the need for ostrich plumes in European and American markets and the rise in consumption of fashion goods based on the ostrich plume, Europe destroyed not only the wild North African ostriches, but also disrupted traditional trans-Saharan trading routes and shifted major Jewish networks to maritime routes on the southern African shores and further inland to places like Oudtshoorn. By expanding the local European luxury consumption of the African ostrich feather, France and Britain transformed the ordinary indigenous consumption of the ostrich egg, leather, and feather into a cash crop (Lefèvre 1914). Hence, they put traditional African economies and their environmental stability at risk, especially as the number of ostriches used for food decreased. By the early 1900s, European fashion industries showed little interest in the ostrich feather following the anti-feather crusade, led by the Audubon society, which was against killing birds for elegance (Doughty 1972, 4) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Postcard of indigenous hunting of ostriches (Courtesy Michael Bonine).

Ostrich plumes and eggs in local African contexts

Without any attempt to be comprehensive, either geographically or chronologically, examples of the wearing of ostrich plumes by African cultures illustrate their widespread use as a statement of status and importance. These are mainly from nineteenth- or twentieth-century descriptions, rock drawings (de Puigaudeau and Senones 1965) or photographs by travellers (Jackson 1968, 113–115; Monteil 1951, 98; Margueritte 1888, 51), ethnographers, anthropologists, and other scholars and professionals. To be sure, other types of feathers did adorn the head, similar to the significance of displaying cowry shells, but ostrich feathers were often the most prominent and important plume indicating either authority or a particular status and accomplishment.

Hats and headdresses were part of the representation of social and ceremonial practices and the visualisation of power and status relations in specific societies. As Arnoldi and Kreamer emphasise:

Headgear and hair styles can no longer be viewed simply as passive reflections of culture. [ … ] Hats and hairstyles, as well as other material objects, need to be understood as one of the technologies that people use to construct social identities and to produce, reproduce, and transform their relationships and situations through time. (1995, 9)

Within sub-Saharan African tribes, the head (and rest of the body) often was highly decorated, an expression of identity and social standing as well as a metaphor for the larger community. ‘In the thought and moral imagination of many African and African diaspora societies, the head, itself, is a potent image that plays a central role in how the person is conceptualized’ (Arnoldi and Kreamer 1995, 11). Hence headwear and headdresses (and hair styles) are attempts ‘to transform their heads and by extension their whole bodies into cultural entities’ (Arnol...