![]()

Comparing super-diversity

Fran Meissner and Steven Vertovec

Reflecting a broadening interest in finding new ways to talk about contemporary social complexity, the concept of ‘super-diversity’ has received considerable attention since it was introduced in this journal in 2007. Many utilizing the term have referred only to ‘more ethnicities’ rather than to the term’s fuller, original intention of recognizing multidimensional shifts in migration patterns. These entail a worldwide diversification of migration channels, differentiations of legal statuses, diverging patterns of gender and age, and variance in migrants’ human capital. In this special issue of Ethnic and Racial Studies, the concept is subject to two modes of comparison: (1) side-by-side studies contrasting different places and emergent conditions of super-diversity; and (2) juxtaposed arguments that have differentially found use in utilizing or criticizing super-diversity descriptively, methodologically or with reference to policy and public practice. The contributions discuss super-diversity and its implications in nine cities located in eight countries and four continents.

Addressing a set of transformations triggered by shifts in global migration, the concept of ‘super-diversity’ has received considerable attention since it was first introduced (Vertovec 2005). Indeed, the Ethnic and Racial Studies article in which the concept was elaborated (Vertovec 2007) has become the most cited in the journal’s history. Moreover, super-diversity has been adopted across a variety of social science disciplines. While this naturally includes studies in sociology and migration studies (e.g. Robinson 2010; Wright 2010; Knowles 2012), the concept has also been invoked in law, economics, demography, business studies, urban planning, linguistics, education, social work and health-care studies (e.g. Shah 2008; Spoonley and Butcher 2009; Batsleer and Davies 2010; Baycan-Levent 2010; Phillimore 2011; Nathan 2011; Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon 2011; Blommaert and Rampton 2012; Aspinall 2012). Super-diversity has also emerged as a key feature of public policy studies (including Hickman, Crowley, and Mai 2008; Fanshawe and Sriskandarajah 2010; Fermin 2011), a cornerstone of new urban policy approaches (City of Birmingham 2012), and a focus of discussion among public intellectuals like Trevor Phillips (2008) and Tariq Ramadan (2011) and within public institutions such as the International Institute for Visual Arts,1 the Westminster faith debates2 and the Kosmopolis urban network.3 As attested by these assorted sites of usage, the concept seemingly appeals to many who address various kinds of contemporary social complexity.

Despite its current popularity (a cause itself for criticism by some who are sceptical of any notion that seems ‘trendy’), it is clear that super-diversity remains a conceptual work in progress. For instance, at the 2013 annual conference of the Association of American Geographers in Los Angeles, a session was devoted to ‘Superdiversity and urban multiculture’. Organized by Sarah Neal and Allan Cochrane, the session description suggested that: ‘The concept of super-diversity has now become familiar sociological shorthand for capturing and describing this new multicultural condition of the 21st century.’ ‘However,’ the organizers were quick to add, ‘developing its theoretical and empirical formations remains an ongoing project for researchers in the field.’ To be sure, like any sociological concept, super-diversity can and should always be critically interrogated, refined and extrapolated by way of fresh data.

Super-diversity can be elaborated in a number of ways, not least stemming from the original way in which the concept was offered. That is, by suggesting the concept of super-diversity, Vertovec (2007) intended to highlight three connected aspects. These have – as often as not – been acknowledged in the various ways and places that the term has been invoked by others. The first aspect is descriptive. Super-diversity is a term coined to portray changing population configurations particularly arising from global migration flows over the past thirty-odd years. The changing configurations not only entail the movement of people from more varied national, ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds, but also the ways that shifts concerning these categories or attributes coincide with a worldwide diversification of movement flows through specific migration channels (such as work permit programmes, mobilities created by EU enlargement, ever-changing refugee and ‘mixed migration’ flows, undocumented movements, student migration, family reunion, and so on); the changing compositions of various migration channels themselves entail ongoing differentiations of legal statuses (conditions, rights and restrictions), diverging patterns of gender and age, and variance in migrants’ human capital (education, work skills and experience). The 2007 article drew on a range of data sources showing how diverse the UK’s and London’s population is with reference to net inflows, countries of origin, languages, religions, migration channels and immigration statuses, gender, age, space/place, and practices of transnationalism. Super-diversity is proposed as a ‘summary term’ to encapsulate a range of such changing variables surrounding migration patterns – and, significantly, their interlinkages – which amount to a recognition of complexities that supersede previous patterns and perceptions of migration-driven diversity.

Arising from the recognition of such simultaneous shifts in migration characteristics and patterns, the second aspect of super-diversity is methodological. This entails a call to reorient some fundamental approaches within the social scientific study of migration in order to address and to better understand complex and arguably new social formations. Much of the history of migration studies has been comprised of research focused on particular ethnic or national groups, their migration processes, community formation, trajectory of assimilation (in the American sense), and latterly their patterns of transnationalism. Super-diversity underlines the necessity to re-tool our theories and methods, not least in order to move beyond what some call the ‘ethno-focal lens’ of most approaches within conventional migration studies. Given such re-tooling, a super-diversity approach holds the potential for novel insights in: rethinking patterns of inequality, prejudice and segregation; gaining a more nuanced understanding of social interactions, cosmopolitanism and creolization; elaborating theories of mobility; and obfuscating the spurious dualism of transnationalism versus integration.

The third aspect posed by the term is practical, or policy-oriented. Super-diversity highlights the need for policymakers and public service practitioners to recognize new conditions created by the concurrent characteristics of global migration and population change (see articles in this issue by Phillimore 2014 and Boccagni 2014). This, too, should entail a shift from ‘ethno-focal’ (or ‘community’-based) policies and services, and a call for greater attention to matters like legal status (and the ways that it often articulates with migration channel, ethnicity and gender).

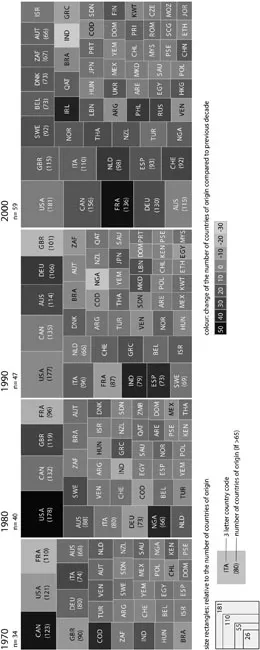

Across all the ways and locations in which super-diversity has been adopted in social science, public debate and policy, the mutual nature of these three interconnected aspects of super-diversity are very often lost. In as much as we can gather, most of the time – in publications, conferences and other academic forums, policy documents and public discussions – people use super-diversity simply to mean the increasing presence of ‘more ethnic groups’. With such a view, some critics of the super-diversity concept have disputed whether, or how much, recent migration has entailed a marked diversification of countries of origin. Even if ‘more ethnic groups’ was not the intended meaning, reports by the World Bank, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the UN indeed describe an undeniable global diversification of migrant’s countries of origin over the past thirty years4 (recent publications that examine global migration flows – even those setting out to challenge the notion of super-diversity – tend to corroborate the diversification of migrant origins; see Czaika and de Haas 2014; Able and Sander 2014; Benton 2013; Connor 2014). Indeed, already more than a decade ago the IOM stressed that ‘Diversification of migration flows and stocks is the new watchword for the current dynamics’ (IOM 2003, 4). For example, a single graphic (Figure 1), visualizing statistics from the UN Population Division’s Global Migration Database, portrays four decades of migration diversification. Each larger rectangle represents one decade and is subdivided into smaller rectangles. Each smaller rectangle shows one country; the size of each smaller rectangle reflects the number of countries of origin for migrants (here with at least 500 people per country of origin). Only those countries with at least twenty-five different groups are included in the figure. Over the decades, we can see a clear, worldwide rise in the number of migrant countries of origin experienced in many countries of the world; the small rectangles in 2000 are more numerous (more countries count more than twenty-five groups of more than 500 individuals) and the size of the decennial rectangle also increases. In addition, Figure 1 shows that these processes of diversification are dynamic and that some countries – granted fewer – are shaded lighter, indicating a decrease in the number of groups from one decade to another. In fact, in 2000 the overwhelming majority (83%) of the 226 countries included in the World Bank global migration database hosted a foreign-born population from more countries than they used to in 1960. Of course, mere country of origin masks further, and usually far more important, forms of diversity – especially ethnicity, religion, language and local/regional identity. Nevertheless, such data and graphics indicate a considerable global trend in migrant diversification. This is even clearer if one looks at urban data and numerous major cities around the world (e.g. Benton-Short, Price, and Friedman 2005). However, such a reading as just ‘more groups’ – ethnic, national or other – falls far short of the intended meanings of super-diversity.

Figure 1. Number of countries of origin for foreign-born/foreign citizens, 1960–2000.

Source: Global Migration Database, World Bank and UN Population Division.

Instead, it is the call for a greater recognition of multi-variable migration configurations that underpins the concept of superdiversity. That social scientists should be aware of the combined workings of several variables is, in itself, not new. For this reason, some feminist scholars have been critical of the super-diversity concept because they feel it overlooks earlier theoretical notions of intersectionality. Intersectionality indeed emphasizes multi-variable effects, but by far most of the intersectionality literature focuses exclusively on the combined workings of race, gender and class. The concept of super-diversity does not challenge anything about theories of intersectionality in this sense; rather, the former is concerned with different categories altogether, most importantly nationality/country of origin/ethnicity, migration channel/legal status and age as well as gender.

In some spheres, commentators speak of the growth of ‘hyperdiversity’ (or use this term interchangeably with super-diversity). We suggest that this is not helpful for two reasons. The first is that hyperdiversity tends to convey the idea that we are merely faced with ‘more diversity’ in terms of ethnicity. This is a unidimensional model that misses the main point argued by super-diversity (again, that several dimensions of migration flows have been changing at once). The second reason why hyperdiversity is an unfortunate term is that ‘hyper-’ can inherently suggest that something is overexcited, out of control and therefore generally negative or undesirable (like hyperactivity or hyperinflation). Again, ‘super-’ is our preferred modifier in order to emphasize the sense of superseding, or addressing what is ‘above and beyond’ what was previously there.

Further, in a variety of publications, there has been divergence on whether the word super-diversity is spelled with a hyphen or without. For very many writers, this does not matter; for others, this punctuation mark can bear meaning. While not wanting to be pedantic or to over-theorize the writing of the word, it might be useful to recall the debate in postcolonial studies: for many scholars in that field, the hyphen’s removal from ‘post-colonial’ implies displacing emphasis from the ‘post-’ in order to create a new sense of a historical condition. A parallel intention surrounds ‘superdiversity’: that is, some scholars suggest that the hyphen may tend to promote the skewed or limited understanding of the term as ‘more’ (ethnic) diversity. Instead, some advocate the removal of the hyphen – hence ‘superdiversity’ – in order to emphasize the multidimensionality of the notion. As within the array of literature in which the concept is adopted, in this special issue one finds different spellings (and under some circumstances the hyphen has its rightful place).

Questions for comparison

Although the notion of superdiversity was initially explored with UK and London data, it has now found a global resonance. This special issue of Ethnic and Racial Studies is intended as a kind of space in which scholars, from a variety of countries, research contexts and disciplines, engage and critique the concept of super-diversity. Here, the concept is subject to two modes of comparison: (1) side-by-side studies in different places, amounting to a parallel look at contexts in which emergent conditions of super-diversity are evident; and (2) juxtaposed arguments that have differentially found use in utilizing or criticizing super-diversity descriptively, methodologically or with reference to policy and public practice. The contributions to this special issue discuss super-diversity and its implications in nine cities located in eight countries and four continents.

An increased, multi-context interest in operationalizing the concept poses important questions that can be grouped into at least two sets. The first set of questions relate to the concept’s comparability, and include: today, is there superdiversity everywhere? Do we speak of differently superdiverse contexts? Is it measurable? What would ‘it’ be that is measured and would speaking of degrees of superdiversity be more sensible? How can superdiversity be built into a comprehensive global comparative perspective that will foster innovative research on contemporary (and past) social patterns without losing sight of context-specific configurations of diversity?

Once these questions have been considered, a second set of questions should be posed if the intention is to develop and extend the superdive...