- 158 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this unique book the author explores the history of pioneering computer art and its contribution to art history by way of examining Ernest Edmonds' art from the late 1960s to the present day. Edmonds' inventions of new concepts, tools and forms of art, along with his close involvement with the communities of computer artists, constructive artists and computer technologists, provides the context for discussion of the origins and implications of the relationship between art and technology. Drawing on interviews with Edmonds and primary research in archives of his work, the book offers a new contribution to the history of the development of digital art and places Edmonds' work in the context of contemporary art history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Generative Systems Art by Francesca Franco in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1The 1960s

From figurative art to colour abstraction

Introduction

This chapter explores the early work of Ernest Edmonds and places it in the social and cultural context of Britain in the 1960s. His youthful artistic inclinations were soon evident to peers through his facility for drawing cartoons and painting portraits. But it is the transition from figuration to abstraction, in his early twenties, which represents the most significant step in the development of his thinking as an artist. The chapter discusses his early paintings and explores how abstract concepts emerged in his first non-representational compositions. As the story will demonstrate, a passion for art, including music, painting and poetry, encounters with influential teachers and mentors and the rich intellectual climate that marked that rebellious, countercultural age awakened in him a strong desire to experiment with a variety of artistic structures, compositions and styles. All these forces were at work as he built the foundations of his groundbreaking piece Nineteen (1968–1969), which for the first time involved writing a computer program as an integral part of his creative process.

“Art or mathematics?”

Edmonds’ earliest recollection of his interest in art dates back to the early 1950s, when he was in primary school in Mitcham, Surrey. He was about ten years old and enjoyed drawing cartoons of his teachers. What surprised him when he showed this work to others was that, despite the fact that he did not think those drawings were anything special, his friends could recognise each one of the teachers in them. Whether this memory had an influence on his motivation or not, the power of drawing somehow struck him as unique. This, coupled with an encouraging art teacher who introduced him to the basics of painting and its technicalities as well as the Masters, caused him to choose Art as one of his subjects of advanced studies at the age of sixteen. To his surprise, the Head of the secondary school, knowing the young student’s abilities in Mathematics and Science, refused to allow him to choose Art as a major subject, but as a compromise offered Edmonds free access to the school’s evening art classes for adults. As a result, at the age of seventeen, as well as focusing his studies on Mathematics and Physics, Edmonds went to painting classes once a week. It was there that he started studying composition and began to experiment with basic techniques, including charcoal and oil paint.

The young Edmonds’ formal studies in mathematics and painting were, however, only a part of his intellectual and cultural pursuits. He read avidly, wrote poetry and struggled to master the trumpet, among many other things. Visits to London’s great national and commercial galleries were frequent, but it was at the Tate Gallery that he first encountered a Paul Cézanne self-portrait and was smitten by the genius of its form and colour. The discovery of Cézanne’s work, and soon after that of Henry Matisse, provided two great inspirations that were going to be key in Edmonds’ future work.

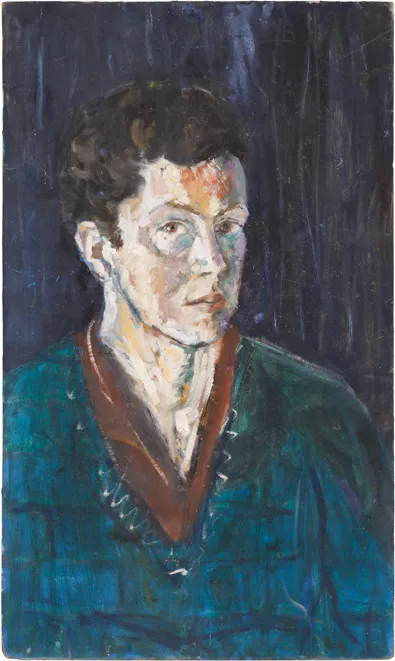

One of Edmonds’ very early paintings, an oil paint on board depicting a vase with flowers, Still Life (1960) (Figure 1.1), shows his instinctive inclination for colour and structured composition unmistakably derived from Matisse and Cézanne. He also maintained his interest in portraiture, which he explored in various styles, some rather stylised, others more experimental, using mostly oil-based paint. Portraits of this period include oil paintings on board representing the artist’s father, a self-portrait (1961) (Figure 1.2), and a study of one of his teacher’s daughters – Edmonds’ first portrait commission.

Figure 1.1Ernest Edmonds, Still Life, 1960.

Source: Image courtesy of Jules Lister.

Figure 1.2Ernest Edmonds, Self-portrait, 1961.

Source: Image courtesy of Jules Lister.

From figurative art to black and white abstraction (1960–1962)

When the time came to choose a tertiary course, Edmonds was keen to pursue studies in art further but uncertain about whether art college was the right way to go. One of his closest friends – rather influential knowing how things developed in Edmonds’ future career – was a year ahead of him and going to art school. He gave him quite direct advice when he said “Don’t go to art school, it’s a waste of time, you don’t learn anything.”1 As going to university was expected of him, he applied for courses at three different institutions: Mathematics at Leicester University, Statistics at the London School of Economics (LSE) and Psychology at a university the name of which he has long forgotten. Both Leicester and the LSE made him offers of a place, and he chose Mathematics at Leicester. Leaving London to go 100 miles north to a red-brick university instead of the more prestigious LSE was a surprising step at the time, and it was to have a profound effect on the course of his ongoing artistic journey. Edmonds was to be introduced to Logic, a subject that he was to follow through later in an MSc and a PhD at Nottingham University.

The socio-cultural environment of England in the 1960s was extremely dynamic and stimulating, and played an important role in Edmonds’ development both intellectually and artistically. As a schoolboy, he explored classical music, including buying second-hand records at Tooting Market, London. One of them contained Schoenberg’s Five Pieces for Orchestra, which introduced him to the composer and remains one of his favourite pieces of music today. Also while still at school, as well as at university, he was an avid listener to the BBC’s Third Programme (now BBC Radio 3) and discovered many contemporary composers – as well as writers – from the broadcasts, including John Cage and Pierre Boulez. Schoenberg, Cage and Boulez all had an influence on his art in later years. While at university, he would often travel back to London to absorb as much as he could from the bustling capital. He was an avid jazz fan from his schooldays and on into university life, often going to clubs, such as Ronnie Scott’s and the Marquee, to hear the best of modern jazz available in the UK, and regularly discussed his discoveries with his friends once back in Leicester. Edmonds took an active part in university life, taking a role in the Students’ Union, where he contributed to the students’ magazines and helped buy paintings to form a local collection. As he recalls:

It was a time of openness, when you could do all these things. Students were doing more at that time. It was an interesting time in that respect. It was an optimistic time, which is a crucial thing; a time where you felt you could do anything, you could have big ambitions, and I did have big ambitions. They were not financial ambitions, or job ambitions, I didn’t have ambitions in either of those directions, but ambitions in terms of what you wanted to achieve, who you wanted to meet.2

One of his recollections of the time is that approaching artists was easier and more straightforward than today. One such artist, John Hubbard (b. 1931), was an American-born artist living in Dorset. His coloured abstract works aroused Edmonds’ curiosity so vividly that he decided to contact him to borrow some of his works for a show at Leicester University, and eventually purchased one of his studies for the Students’ Union.3

There was also a vibrant interaction between different faculties at Leicester University in the 1960s. Although Edmonds had enrolled for a Mathematics degree there, he also attended a course on Philosophy of Science as a subsidiary subject. The Head of Mathematics was Professor R. L. Goodstein, a distinguished logician, who advised him to take the Philosophy subsidiary. His connections with the Philosophy department grew stronger, and, while maintaining a good but more formal relationship with the faculty of Mathematics and its staff, he found a stronger affinity with lecturers and students in Philosophy. One of his Philosophy lecturers, Bob McGown, was particularly interested in Edmonds’ artistic developments, and thought it would be beneficial to him to be introduced to the staff and students of the foundation course at Leicester College of Art, led by Tom Hudson. Hudson was an inspiring figure moved by socialist ideals and international influences, including the Constructivist and De Stijl movements, who created an integrated system of art and design education in the early 1960s. Hudson’s input to Leicester College of Art was particularly influential, as his ideals were close to those of his mentor, the British pioneer of Abstract art Victor Pasmore. In 1954, Hudson had joined with artist and art teacher Harry Thubron to lead a series of summer schools for teachers at Scarborough, applying the principles of what became known as Basic Design, a new foundation course inspired by Bauhaus principles that introduced modernist teaching methods into the traditional education system. The new methodology, focused on the “stripping back of the students’ preconceived ideas by means of practical exercises in form, colour and space”,4 was in line with the innovative ideas on the role of art in education developed independently by Herbert Read from the early 1940s. Thubron later became Head of Painting at Leicester College in 1965. The Leicester College of Art would later be incorporated into Leicester Polytechnic. In terms of teaching, it was one of the few avant-garde art colleges in the country to adopt methods ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Information

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The 1960s: From figurative art to colour abstraction

- 2 The 1970s: Logic, computers and communication

- 3 The 1980s: Constructivism and Systems

- 4 The 1990s: Correspondences and intersections

- 5 Interactive Generative art: 2000–2015

- 6 Structure and systems

- 7 New media, new technologies and new systems

- Conclusions

- Endorsements

- Bibliography

- Index