- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mechanical Deburring and Surface Finishing Technology

About this book

This handbook focuses on product application principles in the design, development, engineering, and shop floor techniques of deburring, edge contouring, and surface-conditioning methods, systems, and processes highlighting semi-automatic equipment, robotics, automated machinery, and computer-contro

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

Mechanical deburring and surface finishing with power-driven brushes and buffs had its serious beginnings in the mid-1940s with the advent of bench and pedestal floor grinders, along with elementary portable handheld air and electric power tools.

Prior to that time, brushes and buffs were manually held and applied to the work with human muscle and hand strength. A typical example of the early methods in the steel fabricating industry, where welded joints were made, was to break up the flux and scale with a hand-held chipping hammer and follow up manually with a wood-backed wire hand scratch brush to clean the loose and loosely adhering debris away.

Similar examples were applied in the buffing area, where buff materials with cutting and coloring compounds were used to achieve metal finishes by tedious and laborious hand rubbing and wiping.

MECHANICAL OPERATIONS

By the late 1940s and early 1950s, as industry geared its factories and manufacturing facilities to the high production of consumer goods, a great deal of emphasis and focus was placed upon mechanizing operations by adding semiautomatic machinery and equipment to replace the hand labor operations. This change in direction toward mechanization created a need for good quality mechanical power-driven brushing and buffing tools that did not exist, and these tools were developed on a rapid basis to meet the ever growing needs of industry.

As new turning, boring, milling, shaping, drilling, and other special machinery was developed and put into operation, a secondary operation was created to remove burrs (deburring) created by the primary machining and metal removal operations. Also, sharp edges needed to be blended, rounded, or radiused (edge contouring) to design-engineered specifications. Flat surfaces and contoured ones needed to be cleaned, smoothed, polished, buffed to a high luster, and, in some cases, roughed for providing additional surface area prior to the bonding of other materials (surface conditioning).

The combination of new state-of-the-art production machinery, equipment, tooling, and power brush and buff tools provided high-volume productivity and good, consistent quality parts, manufactured on a reliable and predictable basis, and easily assembled into component assemblies and/or final products.

From the early 1950s through the late 1960s, a tremendous amount of development work was done by many brush and buff companies in the area of fill (filler) materials, such as wire, synthetics, natural fibers, cloth, and abrasive compounds, as well as on design and construction of various types, sizes, shapes, and geometries of the finished products. This evolution took place to meet the industry demands for their ever-increasing and changing parts and components design improvements and to meet the product application requirements as they became more critical. Besides brush and buff companies, there were other competitive methods for companies, such as mass media finishing, coated and flexible abrasives, carbide tools, and other special processes being perfected, competing on the basis of consistent quality, lower end of service costs, and productivity. During this time frame, mechanical finishing evolved into an integral part of many primary manufacturing operations, casting aside the misnomer of being only a secondary operation that was performed when needed and as an afterthought often overlooked by the design engineering and manufacturing group. Illustrating the point is the automotive transmission gear manufacturing process, which, during this time, added wire brushing to deburr and edge-blend gear tooth profiles after the gear cutting operations. Both are primary operations and necessary for the consistent-quality, trouble-free, high-performance transmissions.

SOPHISTICATED MATERIALS AND PROCESSES

Enter the 1970s, with its rapidly growing electronics industry and applications, sophisticated new high-technology metals and materials, and improved manufacturing systems processes, which accelerated the changes in brush and buff technologies, applications, fill materials, and tool design and construction.

Emerging developments in the areas of plastics, comprising composite and advanced composites materials (favored particularly for the ratio of high strength to light weight), found their way into the aerospace, aerostructures, aircraft engine, and automotive industries. This created new problems and opportunities for the mechanical finishing industry. Entire new concepts, applications, and tool products were developed to replace the tools used on applications replaced by the composite materials.

An extremely important brush fill material developed during this period was the abrasive/nylon monofilaments that can be made into flexible abrading and grinding tools to conform to flat, interrupted, and contoured surfaces of metallic and nonmetallic parts. Buffs comprised of cotton and synthetic fabrics with abrasive grains attached with adhesive were also under development during this time.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Since the early 1980s there has been a proliferation of advanced, sophisticated, precision, computer-controlled machinery, equipment, systems, and processes, focusing not only on the four major material removal methods of turning, drilling, milling, and grinding, but also all others.

Separate deburring, edge contouring, and surface finishing machinery, equipment, robots, cells, systems, and processes, complete with computerized controls and handling systems, enabled industry to minimize much of the hand deburring still being done in the deburring department or on “burr benches” in some shops.

Most recently, flexible abrasive finishing tools, designed for deburring, edge contouring, surface conditioning, and cleaning, have been integrated into NC (numerical controlled) and CNC (computer numerical controlled) machine cycles, directly following the turning, drilling, milling, and grinding operations. With the multiplicity of tool holders in the magazine, cutting and finishing tools can be accommodated to completely machine, finish, and inspect the piece parts in one machine cycle operation without any off-machine operations or people needed.

The success of these new recent developments is attributed for the most part to the design, development, and engineering of flexible abrasive finishing tools, with very little activity in conventional wire and natural fiber brushes, buffs, and abrasive compounds. The rationale is based on the use of abrasive and superabrasive minerals, which can remove amounts of any material. The tools are made with greater accuracy and concentricity, and with exact balance, uniform predictability, and positive reliability in performance.

With the dynamic technological changes continually taking place in industry worldwide, what worked well five years ago in the environment of that time is not acceptable in today’s state-of-the-art conditions.

New products, tools, materials, ideas, and creativity are being generated by most tool manufacturers today and will continue through the rest of this century and beyond. It is absolutely essential to the survival of our manufacturing industries, because of the competitive nature of the global marketplace.

2

Cutting and Grinding Fill Materials

Industrial power-driven brushes and buffs used for mechanical deburring and surface finishing are inherently flexible tools that depend on the fill materials, which do the work, to bend and recover within their elastic limits. Contacting flat or irregular contoured surfaces, the rotating fill materials continually strike, impact, wipe, cut, and grind the work—then instantaneously recover—only to repeat the process cycle again and again until the tool reaches the end of its life cycle and is replaced.

Selection of the proper fill materials is the single most important criterion in achieving the performance results desired at the lowest end-of-service costs expected.

Although some of these fill materials are man-made and others are from natural sources, they are known collectively as brush or buff fill material. These materials include tempered and untempered high-tensile steel wires, annealed stainless steel wires, and a number of nonferrous wires such as brass, nickel silver, beryllium copper, titanium, and zirconium. Other steel wires are brass, zinc, and/or plastic coated, basically for appearance or corrosion resistance.

Abrasive monofilaments, clustered abrasive monofilaments, plastic-coated fiberglass, nylon, polypropylene, polyester, and carbon/graphite lead the growing list of man-made fill materials.

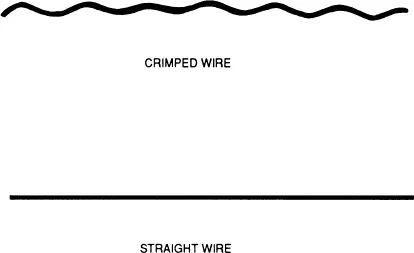

All of the man-made fill materials for power brushes are provided in two basic forms. The first form is straight; the other form is crimped. Crimped fill material is produced by processing the straight material through two gear sets (offset by 90 degrees), thereby introducing a predetermined, consistent, and uniform amplitude and frequency. Figure 2.1 illustrates this.

Natural fiber, which is to say, materials grown by nature, include tampico, sisal, bass, bassine, bahia, palmetto, palmyra, cotton, linen, and others of less consequence. These make up the majority of fill materials. In some cases, specialized combinations of fibers are used for specific applications by mixing together portions of each basic fiber.

Carbon steel wire has been known and used in industry for over 50 years. It was not until the late 1940s and early 1950s that the development of high-tensile oil-tempered brush wire took place. Over the years, the much improved fatigue resistance and superior cutting characteristics of the wires accounted for the rapid growth of industrial power-driven brushes.

STEEL WIRE

Tempered Carbon Steel Wire

Tempered carbon steel wire is still used in power brushes more so than any other fill materials, with the tempered predominating over the untempered, hard-drawn variety. This steel wire is high-quality material similar to that used in springs and other special engineered products. It is generally made from 0.68% to 0.75% carbon steel rod with tensile strengths ranging from 320,000 to 380,000 psi (pounds per square inch) developed at the wire drawing mills. Because of the millions of cycles of compressive and linear stresses to which the filaments are subjected, it is very important that the wires be able to withstand repeated flexing without premature fatigue and breakage. The wire must be bright finished and free of pits, die marks, rust, scale, scrapes, splits, laps, cracks, seams, and excessive decarburization. A grade of tempered wire with lower tensile strengths ranging from 180,000 to 320,000 psi and 0.60% to 0.70% carbon content is also used where the resistance to abrasion and the service requirements are not as demanding.

Figure 2.1 Basic forms of man-made fill materials.

Untempered Carbon Steel Wires

Untempered carbon steel wires are hard drawn to their highest tensile strength and are usually coppered or liquor finished. The solution-drawn wire has an extremely smooth, thin, residual finish coating. Three grades are normally used.

1. Low-carbon brush wire (0.14% to 0.20% carbon) with a tensile strength of approximately 140,000 psi.

2. Hand-scratch brush wire (0.45% to 0.60% carbon) with a tensile strength of 230,000 to 290,000 psi, depending on the diameter of the wire.

3. High-strength wire (0.60% to 0.75% carbon) with a tensile strength of 300,000 to 380,000 psi, depending on the diameter of the wire.

The low-carbon brush wire is commonly produced in sizes of 0.002 to 0.006 inches in diameter, while hand-scratch brush wire and high-strength wire are usually produced in diameters ranging from 0.006 to 0.035 inches in diameter. Untempered wires do not have a great cutting capability or consistency of physical attributes, nor are they as abrasion-resistant as tempered wires. However, they are lower in cost and are usually adequate for the purposes intended.

Stainless Steel Wire

Stainless steel wire is used primarily for corrosive environments, elevated temperature applications (over 350°F), and where the avoidance or minimization of carbon deposits would be helpful to the work parts being brushed (nontransfer of carbon deposits that cause oxidation).

The most suitable brush wire is bright-finished AISI type 302, which is drawn and annealed to minimum tensile strengths of 320,000 psi. The higher the tensile strength, the better the performance, from a deburring, cutting, or cleaning standpoint. AISI type 304 (lower carbon content) is also suitable as an alternate selection, providing that the tensile strength minimum of type 302 is met or exceeded.

On limited occasions, ANSI type 316 is used for brush fill materials because of its characteristics to better withstand highly corrosive and elevated temperature application environments.

In the austenitic grade of stainless steel wire, AISI type 420 can be used where the possible transfer of carbon is not a hindrance to the work being processed. Applications such as wet scrubbing with water or some chemicals would be a good workable example. Having higher carbon content than type 302, the type 420 steels can be tempered for higher tensile properties, thereby giving better life and cut performance. Yet with these advantages it does not come close to matching the life and cut performance of the high-tensile-strength carbon steel wire discussed earlier.

There are some applications where it is desirable to use brushes with nonmagnetic stainless steel wire. Untempered type 302 steel, when drawn to quality used in brushes, can be attracted by a magnet to varying degrees. The amount of magnetic attraction for a given size of wire in the tensile range is a function of the degree of cold working that the wire has undergone. Cold working increases the tensile strength and, simultaneously, the magnetic permeability of the wire. Only in its fully annealed condition can type 302 stainless steel be considered essentially nonmagnetic because in this state it exhibits the lowest permeability.

A unique industrial application for type 321 stainless steel wire fill material is in the hearth-style annealing furnaces used to process aluminum plate and cut sheet. With elevated temperatures of 1050°F (566°C) in some heating zones, many in-line wide-face cylinder brush rolls, slowly rotating in unison, support (by column strength) and convey the large plates and cut sheet through the multizone furnace. The brush rolls (rollers) are located inside the furnace and are subjected to elevated temperatures for years without deterioration. Replacement of the brush rolls occurs only when they are subjected to physical damage caused by an out-of-specification heavy plate curled edge hitting the brush roll directly and damaging the fill material beyond...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Cutting and Grinding Fill Materials

- 3 Product Categories

- 4 Construction Design Criteria

- 5 Applications, Technical Data, and Costs

- 6 Emerging and Future Trends

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Mechanical Deburring and Surface Finishing Technology by Scheider,Alfred F. Scheider in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Industrial Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.