- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1979. Concern about the processes at work in Britain's urban areas, coupled with steep declines in the population projections, led to a review of urban and regional policies in the mid-1970s, with major implications for the new towns as an element of national policy. The various stages and the conclusions of this re-appraisal are discussed, and the new towns' role in the supposed 'urban crisis' is analysed. This title will be of interest to students of urban studies and development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The British New Towns by Meryl Aldridge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Human Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| 1 | The new town idea 1898–1939 |

The dream is broken, the ugly nineteenth century has been wiped off the slate and the country has resumed its natural evolution from the eighteenth century . . . (MacFadyen, 1933, p. 29).

I think it was the persistency with which our group struck to one objective, and even over-simplified it, that lodged the idea in the public mind (Mumford and Osborn, 1971, p. 145).

British new towns are famous throughout the world as an ambitious government initiative. They are among the earliest examples of comprehensive urban planning and have a reputation as social experiments. Yet it was the tenacity and even eccentricity of two men that transformed, over the course of nearly fifty years, an inventor's obsession into a major piece of public policy. Ebenezer Howard had the idea; F. J. Osborn had the dedication, the political acumen and the longevity to keep it on the public agenda until new towns were enshrined in legislation.

The idea

Britain's nineteenth-century urban problems are now well documented. Between 1801 and 1901 the population of England, Wales and Scotland grew from 10,501,000 to 37,000,000 (Ashworth, 1954, p. 7) by a combination of rising fertility and falling mortality. At the same time the population was moving from the countryside to the towns. The percentage of the population living in towns of more than 100,000 residents grew from nil in 1801 to 17·3 in 1891, and that in towns of 20,000 to 100,000 tripled to 21·8 per cent (ibid., p. 8). The quality of city life became a major preoccupation of social philosophers, philanthropists and public administrators alike in the second half of the century. Ashworth (1954), Cherry (1972) and Petersen (1968) have described how hatred of the new cities brought together strange political bedfellows. Those who feared insurrection by the uncontrolled hordes, and those who were appalled at the exploitation of the urban working class shared a conviction that radical measures were needed. Early public intervention centred on health. Precipitated by the cholera epidemic of 1848, the Public Health Act of that year gave local authorities powers over sewerage, water supply, cemeteries and a number of other matters. Gradually regulation was applied to building standards and the provision of working-class housing. (See Ashworth, 1954, for a comprehensive history of the development of town planning legislation.)

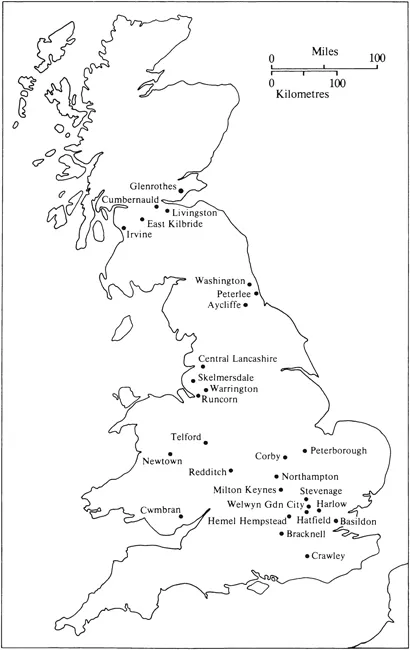

Figure 1Towns in England and Wales, designated under the New Towns Acts

By the turn of the century a new dimension had been added to the urban question. Whereas the problems had been those of concentration, suddenly the development of public transport systems allowed an explosion in the area of towns and cities (Hall et al., 1973, vol. 1, pp. 76ff). It is hardly surprising, therefore, that when Ebenezer Howard published Tomorrow: a Peaceful Path to Real Reform in 1898 his devastatingly simple – even simplistic – scheme attracted so much interest. It seemed at once to solve the problems of overcrowding and ill-health, of congestion and of sprawl.

Ebenezer Howard left school at the age of fifteen, in 1865. For the next six years he drifted ‘from one insignificant job to another’ before he went to the United States with two friends. Finding himself a failure at farming, he returned to office work in Chicago, where he became a reporter for the courts and press. In 1876 he came home to England, where he joined Gurney's as a parliamentary reporter. He stayed in this type of work for the rest of his career. F. J. Osborn writes of him, in the Preface to the 1965 edition of Garden Cities of Tomorrow:

His life was always one of hard work and little income; his interest was never seriously in his own economic prosperity, but was divided between mechanical invention and the movement that made him famous . . . almost always he had a small workshop somewhere in which a mechanic was working on his ideas. . . . In his spare time the young Howard moved in earnest circles of nonconformist churchmen . . . overlapping with others of mild reformists who in those days were largely concerned with the land question (Howard, 1965, pp. 19–20).

Apparently Howard, although mild-mannered and ordinary in appearance, was a natural orator. ‘On the platform he was most impressive and seemed of a dominating type’ (ibid., p. 23).

As a young man, Howard had been a Fabian. The philosophy of his scheme would today be considered liberal in that he advocated a degree of collective action to provide improved urban facilities and opportunities, but favoured a mixed economy to provide the housing, industry and commerce for his garden cities. Howard did not, however, have an explicit political platform which undoubtedly explains the heterogeneity of his support. Nor was he interested in aesthetics. The garden city idea was part of Howard's fascination with technical invention and he presented it essentially as a complex and innovative machine. This is certainly not to suggest that Howard was unaware of, or uninterested in, human problems. One could describe his vision as ‘organic’ but the imagery would lack the sense of the positive application of the new human skills and knowledge by which Howard was so fascinated.

The physical plan presented in Tomorrow: a Peaceful Path to Real Reform is brief. It suggests cities of 6,000 acres. About 1,000 acres would be devoted to the city itself, in a circular form, and the rest to an agricultural estate. The two would be interdependent and together virtually self-sufficient (Howard, 1965, pp. 50ff.). In due course a cluster of such cities would grow up, linked by rapid rail transport, although each would be administratively autonomous, thus forming a ‘social city’ (ibid., pp. 138ff.). Howard suggested that the population of the garden cities would be about 32,000, and speculated briefly on the advantages of a peripheral railway, circular boulevards and a central park surrounded by a ‘Crystal Palace’ (ibid., p. 54) or wide glass arcade to tempt people outdoors whatever the weather. He remarks, however, that these ideas are ‘merely suggestive and will probably be much departed from’ (ibid., p. 51). Clearly he felt his real contribution was in the administrative devices that he recommended. Land would be purchased by a company formed for the purpose and owned by the municipality. Other organizations and individuals would lease sites for building. The ‘rate rent’ that they paid would then be used to repay the loan, and the surplus (he was confident that there would be one) ploughed into the provision of municipal facilities. Considerable space in the book is devoted to issues of, for example, temperance, the advantages of limited competition for tradesmen and the recycling of the city's sewage for the agricultural estate. Today the scheme seems naive and Utopian, as it did to many contemporary commentators, yet the watchword was always practicality.

Howard came to be a well-known and respected public figure, but it is clear that, while he provided the inspiration, most of the initiatives were taken by others. In 1901 the Garden City Association was founded, under the chairmanship of Ralph (later Mr Justice) Neville, KC. In turn, the Pioneer Company was formed and, in 1903, bought 3,818 acres in Hertfordshire to found Letchworth. (Detailed accounts of this period can be found in the preface to Howard, 1965; MacFadyen, 1933; and Purdom, 1949.)

F. J. Osborn joined the staff at Letchworth in 1912 as a housing manager and quickly established himself in the small group dedicated to promoting the garden-city idea. With Howard, C. B. Purdom and W. G. Taylor, who together formed the National Garden Cities Committee, he wrote New Towns After the War (1942) in 1918. He remained at Letchworth and later Welwyn until 1936 when he transferred to a part-time directorship with a local firm. He thus had time to work for the (by then) Garden City and Town Planning Association as Secretary and then Chairman of the Executive, until 1961. F. J. Osborn edited the Association's journal Town and Country Planning until 1965 when he was 80. Like Howard, Osborn was a ferocious self-educator, reading, going to night-school and belonging to the Fabians as a young man. From his Letters with Lewis Mumford (Mumford and Osborn, 1971), though, he appears more humorous, more politically astute and more this-worldly than does Howard as described by MacFadyen (1933) and others.

The philosophy of the founders

Ebenezer Howard was undoubtedly influenced by nineteenth-century Utopian authors, specifically Bellamy (1851) and Buckingham (1849) and presumably also by the writings and public statements of William Morris, John Ruskin, H. G. Wells and G. K. Chesterton (Petersen, 1968). F. J. Osborn has specifically noted the influence of Wells and Chesterton on his own youth and yet has rejected the Utopian element in the new towns idea: There was no utopianism in my book of 1918 or in the first Garden City prospectus of 1903 or in the New Towns Committee's report of 1946 or in the propaganda of the TCPA since 1899’ (Mumford and Osborn, 1971, p. 253).

Yet some vision of a better life, still to be created, must have informed Osborn in his years of effort for the new towns cause, as it did Howard in his book and his work. The tension between this vision of a changed life and the practical use of existing institutions which runs through his book has been perpetuated in the policies of the TCPA, became embodied in the New Towns Act of 1946 and has characterized the new towns programme to the present time. The British new towns are seen as an experiment in social living, when Howard and Osborn were in many ways conservative about social and family structures, and as redistributive when there is little in the 1946 legislation or subsequent action to bear this out.

It has been suggested that there was created in Britain in the nineteenth century an anti-urbanism that has profoundly affected urban policy and town planning practice ever since. This may be accurate of some intellectuals. William Morris, in News from Nowhere (1891) described his vision of a post-industrial return to a society where medieval face-to-face society combined with egalitarianism. In it the lower Thames is fished for salmon and the Palace of Westminster has become a fruit and vegetable market.

Reading Howard and Osborn, however, it is clear that what motivated much of their rejection of city life was not so much the fear of social disorganization or hatred of industrialism as a conviction that the city by its very nature destroyed physical health, impaired the quality of the race and reduced fertility. The belief about fertility became an even greater preoccupation during the 1930s when the birthrate reached an unprecedentedly low level, thus appearing to lend support to the case of the decentralists. Lewis Mumford, writing to Osborn, expresses this conviction vividly: ‘. . . the big city not merely devours population, but because of its essential nature prevents new babies coming into the world’ (Mumford and Osborn, 1971, p. 61).

From the time that Letchworth was founded, until after the Second World War physical health had much the same status as the major social problem confronting legislators and philanthropists as crime and violence has today.

The solution to both the social and health problems of the urban population was seen by Howard and Osborn to be largely achievable by the provision of a better physical environment. Indeed it also formed part of public policy via the 1918 Tudor Walters report to which Raymond Unwin, an influential early member of the garden cities movement, was a major contributor. Low-density cottage-style developments became the official orthodoxy (Mumford and Osborn, 1971, p. 16). Better housing, more space for recreation, convenient work and welfare facilities undoubtedly have a major influence on health and well-being, but these ideas acquired more than mere practical status in the writings of Howard and Osborn. Contact with nature and the countryside was seen as having a fundamental, almost mystical, significance for the state of mankind. Despite his protestations of practicality, rather than utopianism, Osborn became almost obsessively attached to the idea of these low-density cottage developments at twelve houses to an acre. It is over this that he and Mumford quarrelled more than once, face-to-face and by letter – the only issue that seemed to divide them in more than thirty years’ friendship.

The position you seem to have taken, dear F. J. seems to you an impregnable one because you simply cannot imagine any reasonable man having another point of view than your own, or proceeding from another set of axioms than those which seem to you self-evident (ibid., p. 275).

Propounding his famous ‘two magnets’ principle, Ebenezer Howard too was quite unequivocal:

our kindly mother earth, at once the source of life, of happiness, of wealth and of power. . . . The country is the symbol of God's love and care for man. All that we are and all that we have comes from it. Our bodies are formed of it; to it they return. . . . It is the source of all health, all wealth, all knowledge. But its fullness of joy and wisdom has not revealed itself to man. Nor can it as long as this unholy, unnatural separation of society and nature endures. Town and country must be married (Howard, 1965, pp. 46, 48, emphasis in original).

This passionate advocacy of the countryside as a source of spiritual, as well as physical, regeneration must be the source of one of the recurrent themes of the new towns movement: collective ownership of land. Howard proposes the interim measure of municipal purchase and ownership of the new town sites, but his ultimate aim is clearly that private ownership of land should end. He criticizes ‘our friends, the socialists’ (with whom he had, as did Osborn, extensive sympathies) for placing too much emphasis on the means of production and too little on land. They ‘have thus missed the true path of reform’ (Howard, 1965, pp. 135, 136).

Forty years later, Osborn commended the Uthwatt Committee's proposals for land reform (Mumford and Osborn, 1971, p. 58) and later still referred, quite seriously, to a conspiracy between the LCC architects with their monumental and high-density aesthetic and the countryside preservationists (ibid., p. 204). The conviction of many members of the TCPA that collective ownership of land is an essential precursor to a better life reappears in Schaffer's The New Town Story (1972). In the middle of a careful – almost bland – history of the new towns, the author attacks a system which allows vast unearned profits to be made as a consequence of planning decisions. The thinly veiled passion contrasts oddly with the tone of the rest of the book.

For Howard, his supporters and his colleagues, action was, however, more important than the careful refining of a consistent philosophy. The eclecticism of their ideas reflects the eclecticism of the influences upon them. Howard had been impressed by Bellamy's Looking Backward 2000—1887; he had read it in its American edition and was instrumental in having it published in England. When the novel was published in 1887 it was, according to the introduction of the 1951 edition ‘the most widely read book of [the] times’ (Bellamy, 1951, p. xv). The Utopia is described through the medium of a novel. Boston in 2000 is a city of great beauty where private property, wages and, indeed, all forms of money are absent. Although family and household structure is unaltered, there are municipal eating places and other facilities which contribute to the emancipation of women, a dominant theme of the novel (as it is in William Morris's News from Nowhere, 1891). All citizens are allotted an equal amount of credit to obtain goods and services, unrelated to their work because ‘all who do their best, do the same’ (Bellamy, 1951, p. 74).

Despite the strong emphasis on the collectivity, the author's sympathies are clearly not with centralized socialism. His Utopia has only a vestigial judiciary and legislature because, he claims, once private property disappears most of the need for the apparatus of law disappears, as does taxation. Industry is, however, completely monolithic – a sort of corporate state, regulating its production by demand. Opportunities and incentives for individual effort are introduced by an elaborate system of honours which Bellamy sees as reward enough in a society which has made ‘patriotism a national devotion’ (ibid., p. 206).

Somehow Bellamy contrived a system that combined collectivism and individual incentive, decentralized power and a sophisticated industrial system, equality and a rigid meritocracy. These themes reappeared strongly in Howard's book although his campaign was for a less centralized society in a quiet literal sense. He quite clearly believed that adoption of his plan would result in the redundancy of the great cities.

Ebenezer Howard was not unaware that he was trying to integrate two political philosophies that were then, and still are, defined in terms of their opposition to one another, but he hoped that some blend of individual and municipal effort could be found by experiment:

With a growing intelligence and honesty in municipal enterprise, with greater freedom from control of the central government, it may be found – especially on municipally owned land – that the field of municipal activity may grow so as to embrace a very large area and yet the municipality...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface and acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- 1 The new town idea 1898–1939

- 2 Wartime deliberation; post-war legislation

- 3 The end of the beginning: the Mark One new towns

- 4 Renaissance and redirection 1960–74

- 5 The ownership and management of new town assets

- 6 Balance and self-containment

- 7 Regional growth and urban decline

- 8 Reappraisal 1974–8

- 9 What is the ‘new towns policy’?

- Outline chronology

- Bibliography

- Index