eBook - ePub

Preclinical Drug Disposition

A Laboratory Handbook

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For researchers and students in pharmacology and related fields, explains the standard techniques for investigating the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of test compounds using laboratory animals. Describes types of experiments, study design, animal preparation and maintenance, do

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Preclinical Drug Disposition by Lai-Sing Tse Francis,Lai-Sing TseFrancis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pharmacology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PRECLINICAL DRUG DISPOSITION

1

Introduction

Fundamental Concepts of ADME

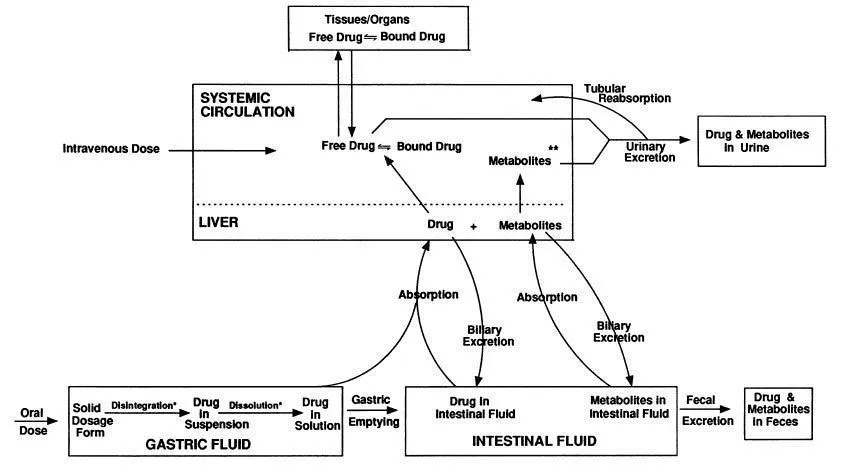

In a broad sense, disposition includes all processes and factors that are involved from the time a drug is administered to the time it is eliminated from the body, either in the unchanged form or as a biotransformation product (metabolite). More specifically, the term encompasses the processes of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), which are depicted in Fig. 1.1.

Absorption

Absorption is the process by which a test compound and its metabolites are transferred from the site of absorption to the systemic circulation. In animal disposition studies, the test compound is most commonly administered orally – either by gavage (intubation) as a solid (e.g., capsule); as a liquid dosage form (e.g., solution, suspension); or, often in rodents, as a drug-food mixture (dietary admixture). In either case, as illustrated in Fig. 1.1, the rate of absorption can be markedly influenced by how rapidly the test material dissolves in the gastrointestinal fluids. This is referred to as the dissolution process and is often the rate-limiting step in the absorption process that can subsequently influence the onset, duration, and intensity of the pharmacological activity of the test substance. For this reason, absorption is usually most rapid and less variable for a solution as compared to a solid dosage form, especially for relatively water-insoluble compounds. Thus various factors that influence solubility such as particle size, salt form, pH, crystalline structure, and solvent systems play an important role in modifying the absorption process and must be considered in designing animal experiments.

FIG. 1.1 Schematic of the processes of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion.

∗ Processes that can occur in the intestinal tract.

∗∗ Similar to the drug, metabolites can be bound or free, and the free metabolite can be distributed to the tissues/organs.

In addition to solubility, other physicochemical factors can also influence the absorption of a drug solution in the gastrointestinal tract. These include instability as a result of digestive enzymes or low gastric pH, and drug complexation due to the presence of dietary components. Other factors such as presystemic metabolism, either in the gut wall or the liver (first-pass effect), which often affect the systemic availability of the parent compound (bioavailability), have relatively minor effects on the total absorption (exposure) of drug and related materials.

In the absence of the above effects, once a compound is in a form (solution) in the gastrointestinal tract that can be absorbed, it will then pass through the gastrointestinal mucosa, a semipermeable membrane, into the blood, normally by a process referred to as passive diffusion. Three factors – the pKa and the lipid solubility of the compound and the pH at the absorption site – will govern its movement through the membrane in this manner. The influence of these is collectively referred to as the pH–partition hypothesis. Thus the nonionized form of an acidic or basic drug will be preferentially absorbed by diffusion, with the driving force for movement through the membrane being the concentration gradient (i.e., the difference between the concentration of solute in the gastrointestinal tract and that in the blood). The greater the proportion of drug in the nonionized to ionized form at the absorption site, the more rapid and efficient the absorption process. Acidic compounds will usually be absorbed from the stomach while basic drugs will be absorbed from the more alkaline milieu of the intestines. Additionally, the rate and extent of absorption are related to the oil/water partition coefficient so that the more lipophilic the compound, the more rapid and efficient is its absorption.

Although most compounds cross the intestinal membrane by a diffusion mechanism, many natural substances such as vitamins and l-amino acids as well as some drugs are absorbed by a structurally specific active transport process in which molecules move from the mucosal to the serosal side of the gastrointestinal tract regardless of the concentration gradient. This is an enzymatic process which can be saturated at high drug concentrations and has the potential for competitive inhibition if two similar substrates are transported by the same carrier mechanism. Also, since the active transport process consumes energy, it can be inhibited by substances that interfere with cell metabolism. Although other absorption mechanisms such as facilitated diffusion, pinocytosis, convective absorption, ion-pair absorption, and lymphatic absorption have been identified and can also be important, they are responsible for the transport of relatively few compounds.

Distribution

After entering the bloodstream, the molecules of the compound mix with body fluids and are then distributed to the site of action. Initially, the highly perfused organs (heart, liver, kidney) receive the majority of the dose with delivery of the compound to organs such as muscle, skin, and fat much more slowly. The differences between organs in lipophilicity, blood supply, and ability to interact with foreign substances make drug concentrations non-uniform throughout the body. Thus the distribution of a compound can have a profound effect on the onset, intensity, and duration of pharmacological response.

The distribution of compounds in the blood into its various components (red cells, white cells, plasma proteins, plasma water) is important since only the free drug (see Fig. 1.1) distributes to body tissues. Due to specific binding, for example to plasma proteins, hemoglobin, and blood cell walls, there can be substantial differences between circulating whole blood and plasma concentrations of the administered compound. Thus it is critical to clearly define the type of biological sample utilized for analysis.

The main interaction in the blood is the binding to various plasma proteins, mainly albumin for acidic drugs and α1-acid glycoprotein for basic compounds. Most binding is by reversible physical forces, and stronger (covalent) binding is rare. Also, since the binding site on acids is usually the N-terminal amino acid while bases appear to bind nonspecifically, the capacity of protein binding to acids is limited while that of binding to bases is usually large. In general, only when the percent binding is high (> 95%) will the plasma serve as a significant storage compartment for compounds.

Outside the blood compartment, molecules that are not bound (free molecules) in the blood and do not have molecular weights of > 500–600 can penetrate the capillary walls and reach the interstitial spaces. An essentially protein-free ultrafiltrate fluid of plasma carries nonprotein-bound materials in either direction across the capillary walls by hydrostatic pressure.

The membranes of the tissues behave in a similar manner to those of the gastrointestinal tract; i.e., lipid soluble, nonprotein–bound molecules pass through the membranes by a passive diffusion process where equilibrium is established between the inside and outside of the tissue. Thus, for most compounds, penetration depends on a favorable un-ionized to ionized ratio. For example lipid-soluble compounds with molecular weights of < 1000 can cross the placental barrier by simple diffusion while the membrane is essentially impregnable to highly polar material. The extent of tissue localization in any particular tissue is related to the physicochemical property of the compound as well as to the ratio of plasma-to-tissue concentration. The rate of tissue localization, though, is mainly dependent on the blood flow to that area. Thus equilibrium occurs rather rapidly in the highly perfused organs such as the kidney and lung, relatively more slowly in moderately perfused muscle tissue and skin, and much more slowly in fat. Like other equilibration processes, tissue localization is usually reversible.

The brain capillaries are surrounded by a cellular sheath that makes them substantially less permeable to water-soluble materials than capillaries found in other areas of the body. This is often referred to as the “blood-brain barrier.” Thus, the ability of compounds to penetrate areas of the central nervous system (CNS) such as the brain, as well as the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), is highly dependent on their lipid solubility (o/w partition coefficient). Compounds with more polar characteristics will show little pharmacological activity in these areas.

Metabolism

Metabolism (biotransformation) is the process by which the administered compound is structurally and/or chemically changed in the body by either enzymatic or nonenzymatic reactions. The pathways by which this occurs are classified as either phase I or phase II reactions. Phase I processes convert the compound by oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis while phase II, often termed conjugation reactions, involves coupling between the compound or its metabolite and endogenous sub-strate, especially glucuronic or sulfuric acid. Although these reactions can take place in various tissues and organs throughout the body, compounds are predominantly metabolized in the liver by microsomal enzymes located in the endoplasmic reticulum. Normally, metabolism results in a molecule that is substantially less active than the parent compound, although in some phase I reactions, the metabolite may be more active than the parent molecule (prodrug). Also, since metabolites are generally more polar than the original compound, their volumes of distribution are reduced and their ability to be eliminated via the kidneys is greatly increased.

The rate of metabolic enzymatic reactions can usually be described by the Michaelis-Menton equation:

where

Vmax | = | the maximum production rate of metabolite |

C | = | the concentration of compound in the blood |

Km | = | the Michaelis constant |

Normally, blood concentrations are much smaller than the Km values associated with their metabolism and the above equation can be written as:

where km is a first-order metabolic rate constant and, thus, the rate of metabolism is proportional to the blood concentration. At elevated concentrations exceeding the saturation level, the rate of metabolism become nonlinear. Thus, the Michaelis-Menten nature of drug metabolism will result in a decrease in the rate of elimination of compounds at higher dose levels (dose-dependent elimination).

The rate of metabolism can also be decreased due to inhibition of the microsomal enzymes (enzyme inhibition), which can be of a competitive or non-competitive nature. Competitive inhibition can occur when structurally similar compounds compete for the same site on the enzyme. In noncompetitive inhibition, a substrate of unrelated structure to the compound undergoing metabolism combines with the enzyme to prevent the formation of an enzyme:compound complex.

An increase (stimulation) in the activity of the microsomal enzymes (enzyme induction) can occur by the administration of certain drugs or by exposure to some chemicals in the environment. For example, barbiturates induce the synthesis of cytochrome P-450 and cytochrome P-450 reductase, which increases enzyme activity leading to a corresponding increase in metabolism of a wide variety of structurally unrelated compounds.

Excretion

Compounds are eliminated from the body as the unchanged molecule or as metabolite(s). As stated previously, in most excretory organs except the lungs, water soluble (polar) substances are excreted more efficiently than those that are relatively lipoidal. Although excretion can take place through numerous pathways such as the bile, feces, milk, saliva, perspiration, tears, and lungs, the most significant organ for elimination is the kidney. Renal excretion involves three processes:

1. Passive glomerular filtration

2. Active tubular secretion

3. Passive tubular reabsorption

The amount of material entering the tubular lumen by filtration is dependent on the filtration rate and the degree of plasma-protein binding. Active tubular secretion occurs in the proximal renal tubule and involves the carrier-mediated transfer of anions or cations from the renal interstitial fluid to the tubular fluid. Weak organic acid and bases are usually involved in this process. In the proximal and distal tubules passive reabsorption of compounds from the glomerular filtrate back into the blood (see Fig. 1.1) is influenced by the intrinsic lipid solubility of the compound, its ionization constant, and the pH of the urine. Thus, compounds of high lipid solubility do not appear in the urine in large proportions because most of the molecules filtered at the glomerulus return to blood by diffusing across the lipidlike boundary of the tubular cells. Conversely, compounds of low lipid solubility are readily excreted in the urine because they are poorly reabsorbed in the tubule. Because of this, the pH of the tubular fluid and the dissociation constant of the compound being excreted often influence the renal tubular transfer of many weak acids and bases, just as these same factors influence the absorption of compounds in the gastrointestinal tract as discussed previously.

Hepatic elimination can also play an important role in the excretion process. Compounds that are metabolized in the liver are often excreted in the bile into the intestinal tract (see Fig. 1.1). Here they can be reabsorbed by passive diffusion into the blood (enterohepatic recycling) or excreted in the feces along with unabsorbed material following oral administration. Factors such as molecular weight, chemical structure, polarity...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Use of Radioactivity in Drug Disposition Studies

- 3. The Rat

- 4. The Mouse

- 5. The Dog

- 6. The Rabbit

- 7. The Monkey

- 8. Data Interpretation

- Appendixes I-V

- Index