- 104 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sustainable Industrialization

About this book

This report, first published in 1996, argues that radical changes in industrial organization and its relationship to society tend to arise in rapidly industrializing countries, and that new principles of sustainable production are more likely to bear fruit in developing than in developed countries. The rising tide of investment by multinational firms – who bring managerial, organizational and technological expertise – is a major resource for achieving this. Developing countries could steer such investment towards environmental goals through coherent and comprehensive policies for sustainable development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sustainable Industrialization by David Wallace in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

It is almost ten years since the Brundtland Commission injected the term and concept of sustainable development into popular and political debate, reflecting and magnifying a wave of concern about the global environment. Five years later, in 1992, sustainable development was given weight and substance (but not, for most people, meaning) by the Rio Earth Summit. Rio, the largest ever international conference, generated conventions on biodiversity and climate change, and generated a vast menu of activities, known as Agenda 21, which would be necessary, although perhaps not sufficient, to lead the world towards sustainable development. Countries and industries alike have pledged themselves to the concept of sustainable development. Some have produced grand statements and plans and a very few have begun to define what sustainable development might mean in practice for their economies and businesses. In 1997 the Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD), the UN body set up to monitor and promote the follow-up to Rio, will gather heads of government from around the world to review progress.

How much progress will there be to report at the CSD? What has been the experience of those countries in the developed world which have taken sustainable development most seriously? How will the debate on the problems and prospects for developing countries be framed? Will the interminable cycle of blame for past damage and claims for costs of avoiding future damage continue to polarize North-South views of the best route towards global sustainability? Can an alternative view based on a belief that developing countries represent the best hope for creating sustainable modern societies be injected into this debate? This report provides a short, critical appraisal of these questions.

The dominant model of sustainable development, embodied in the final agreements of the Earth Summit, assumes a process of leadership and diffusion of new technologies and techniques from the industrialized North to the South. The developed economies and their industries are expected to extend their existing policies and methods to curb pollution and reduce waste, developing clean technologies along the way. The developing world, in the course of its inevitable industrialization, will learn from this experience and come to adopt cleaner technologies and processes through ‘technology transfer’, accelerated by international financial aid provided on the grounds that this is essential to protect the global environment.

This report argues that although such a model is partly right it fails to reflect critical underlying forces and processes and as a consequence is, in its present form, creating deadlock. The apparent failure of the Rio process to advance the political North-South debate much beyond an argument over responsibilities and costs lends weight to the criticisms of the radical greens who are opposed to economic development following the Western model in the South and who advocate quitting the development race in the North.

This report explores these conventional models and finds them both wanting. A robust model for North-South cooperation on sustainable development needs to build on a better understanding of the scale and nature of the challenge, and in particular:

- the historical processes of industrialization;

- the contemporary driving forces of industrialization;

- the nature of major shifts in industrial organization;

- the relationships between industrial organization and the rest of the economy and society.

From this perspective it becomes clear that a sustainable economy will require a production system which is radically different from current models of production not just in terms of technologies but also in motivating principles, inter- and intra-firm structure, and relationships with the wider community and civil society. A historical analysis suggests that radically different organizational structures and mindsets are established much more readily in fresh environments than in previously ‘colonized’ environments, where they must displace the prevailing system. With sustainable development thus identified as a systemic problem, developing countries which are only now embarking on industrialization are seen to be the most likely location for the sustainable industrial economy of the future to emerge, and the limitations of discrete technological fixes within the existing system become apparent.

To explore these issues and their implications for policy-makers, this report is structured as outlined below.

Chapter 2 examines some of the most significant national and corporate responses to the challenge of sustainability in the North. The Dutch national plan, in particular, gives a sobering indication of the scale of the task faced by developed countries. Although some corporations and a few countries are making genuine efforts, progress is likely to be slow because of the need to avoid excessive economic pain and social upheaval.

Chapter 3 analyses critically how far these efforts have taken us. It looks at long-term trends in consumption and pollution in the industrialized world, exposes flaws in recent efforts to portray the North as being set on a path towards sustainability and provides additional insight into the scale and nature of the challenge not just for the North but for a much more populous South apparently set to follow the pattern of development in the North.

Having established that serious efforts in the North are few and far between and that even these anticipate substantial difficulties over long time periods, Chapter 4 takes us back to a fundamental exploration of the links between industrialization, industrial organization and shifts in the dominant industrial paradigm. A historical perspective is used to draw out the importance of greenfield economies in establishing new production paradigms and the critical role of features which evolve gradually in the shift from one paradigm to another. This paradigmatic perspective is used to interpret specific examples of the limitations and barriers to fundamental change in developed economies.

Building on the idea that sustainability requires a paradigm shift and that developing countries present the best opportunity for this to occur, Chapter 5 critically examines the Rio model of North-South relations on sustainable development and finds it wanting. In conventional thinking the main alternative model to Rio (apart from muddling on in the hope that the planet will withstand our assaults) is to turn the clock back to some preindustrial form of society. This too is discussed and found wanting for practical reasons. Chapter 5 proposes an alternative - sustainable industrialization - which is in keeping with the major forces driving rapid industrialization in the South, in particular foreign direct investment.

Chapter 6 explores the role of foreign investment in more detail, emphasizing the importance of the knowledge, organizational skills and technologies of the North in helping to establish sustainable economies. Multinational corporations are seen to be capable of playing a key role in establishing sustainable patterns of industrialization because of the scale of their investments, the knowledge and expertise they bring to bear and the role they can potentially play in shaping a growing economy. By contrast, prospects for international aid alone to play a significant role are seen to be poor. Some encouraging examples of the kind of engagement with developing countries required of multinationals are presented at the end of the chapter.

Chapter 7 deals with the crucial issue of policies for encouraging sustainable industrialization. Policies aimed at raising the game of all foreign investors so that they behave as the best do already are discussed, as are the conditions required for a developing country to feel comfortable with such policies and to administer them effectively. The possibility of a developing country adopting a comprehensive plan for sustainability, and the reasons why this may be much less of a burden (or even a benefit) for a developing country than for an industrialized country are also discussed. Finally, Chapter 7 looks at some examples of comprehensive and farsighted environmental policies in developing countries.

Chapter 8 presents a short discussion and the main conclusions for policy-makers.

Chapter 2

Sustainable development: the Western model

2.1 National strategies

In recent years, and especially since the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992, several industrialized countries have begun to think seriously about how they might create sustainable economies. In a few cases these efforts have led to policies which are now beginning to be implemented. Others remain at the stage of aspirations or plans on paper. Three of the most significant efforts, all in Europe, are discussed below.

2.1.1 The Netherlands - turning the ship around (slowly)

The Dutch National Environmental Policy Plan (NEPP) is the most comprehensive effort to date to create a sustainable economy.1 The policy is founded on an exhaustive survey of the state of the Dutch environment which concluded that emissions of many industrial pollutants would need to be reduced by 70 to 90 per cent by 2010, if long-term environmental disaster was to be avoided.2 This is a far greater aggregate reduction than has been achieved yet in any industrialized country, although reductions of this magnitude for individual pollutants are not unknown. Instead of going down this route, the government promoted the need to ‘internalize the environmental problem’, i.e. the need for greatly increased environmental sensitivity among all citizens, administrative bodies and especially industry.

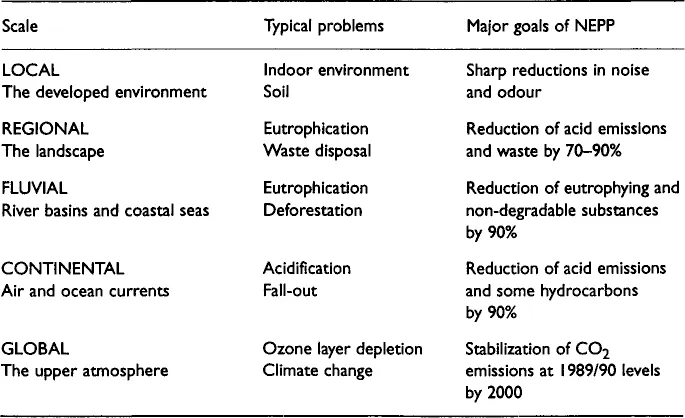

In the NEPP, the environment is regarded as a system of reservoirs, with natural cycles of substances circulating within and between them. There are five geographical scales, ranging from the local to the global level, each with its own environmental problems (see Table 2.1). Problems at one level have effects at higher and lower levels, so that global warming, for example, affects the local environment through the damage caused by extreme weather events. Pollutants diffuse from lower to higher levels, causing environmental problems at each stage. At higher levels, problems take an increasing length of time to become apparent and counter-measures become increasingly difficult and slow to take effect. In the past, environmental policies which have targeted local or regional problems have caused problem-shifting from lower to higher levels.

Table 2.1: The 5-level model in the Dutch NEPP

The goals of the NEPP are to be achieved in three main ways:

- closing substance cycles (the main plank of German policy - discussed below);

- conserving energy and using cleaner energy sources;

- quality enhancement, i.e. promoting the highest quality of production processes and products.

Emissions abatement will be tackled by methods which are:

- emission-oriented - end-of-pipe clean-up techniques;

- volume-oriented - reducing the scale of production; or

- structure-oriented - more efficient and cleaner production and consumption processes.

As the potential for end-of-pipe methods becomes exhausted there will need to be increasing emphasis on volume-oriented methods to meet the targets for 2010. Structure-oriented methods are expected to have an impact only over the longer term.

Widespread application of structure-oriented methods is expected ultimately to transform the Dutch economy. Uptake is constrained by long investment cycles for large-scale developments and the need for structural changes in the economy to take place without excessive social upheaval. Several initiatives aim to explore the changes in design and materials which are necessary for structure-oriented methods to succeed. For example, a government-funded assessment of the environmental impacts of primary manufacturing materials should help manufacturers to include the environmental impact of materials in their design criteria. Worldwide experience to date with cleaner technologies, where many companies have found unexpected cost savings, suggests that if the Dutch can avoid pursuing structure-oriented changes too quickly (and so imposing economic costs), they may in the long run find widespread cost savings across many industries.3 Aggregated at the national level, the transformed economy could be as competitive as before, or even more competitive.

The NEPP identifies ten Target Groups’ which must contribute to meeting the NEPP goals: Agriculture; Traffic and Transport; Industry (including refineries); Energy; Construction; Waste Processing; Water Supply; Environmental Equipment Manufacturers; Research Institutes; Societal Organizations and Consumers.4 So far much effort has been directed towards setting broad targets for the industry target group. Discussions between the government and umbrella industrial organizations produced agreement in principle on a range of targets, such as SO2, NOx and VOC reductions of 80 per cent, 45 per cent and 45-60 per cent respectively, by 2010.

Government and industry agreed that attempting to achieve these reductions through traditional forms of regulation, e.g. imposing uniform emission reductions on all industries, would be costly and inefficient. An ideal mechanism would take account of differences between industrial sectors and firms within the same sector in their ability to make reductions. The solution was a system of agreements between the government...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- About the author

- Acknowledgements

- Executive summary

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Sustainable development: the Western model

- 3 The West’s record on sustainable development

- 4 Production paradigms

- 5 Sustainable development and developing countries: models for change

- 6 The role of foreign investment

- 7 Policy levers for developing countries

- 8 Conclusions