![]()

1

Past history and deaths foretold: nation, self and other from the 1960s to the 1980s

Is that love you're making?

Arthur Osborne, Is That Love You're Making?

The discursive explosion of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries [meant that] what came under scrutiny was the sexuality of children, mad men and women, and criminals; the sensuality of those who did not like the opposite sex; reveries, obsessions, petty manias, or great transports of rage. It was time for all these figures, scarcely noticed in the past, to step forward and speak, to make the difficult confession of what they were. No doubt they were condemned all the same; but they were listened to; and if regular sexuality happened to be questioned once again, it was through a reflux movement, originating in these peripheral sexualities.

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality

Ideal homes

'The death ... of a beautiful woman is unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world, and equally is it beyond doubt that the lips best suited for such topic are those of a bereaved lover' (Poe, 1951, 982). Poe's eulogy of the dead woman as Muse encapsulates a centuries-long tradition – from Dante, Petrarch and Camões through Dickens, Herculano, and Tolstoy to contemporary veneration of vanished icons (Marilyn Monroe, Diana, Princess of Wales) – of worship of the deceased beloved at least partly because deceased. Commenting on Paula Rego's 1997–98 series based on the nineteenth-century Portuguese novel by Eça de Queirós, The Sin of Father Amaro (plates 11-15, figures 34-35, 37-38, 40-41, 45, 47), Ruth Rosengarten draws a contrast between Rego's empowered rendition of the female protagonist and the version given by her literary precursor, whose 'corpse becomes the visible sign of a Christian morality that silences female desire' (Rosengarten, 1999a, 24). In the analysis that follows in this chapter and chapter 2 of paintings from the ten years that preceded the Father Amaro series, I shall pay particular attention to the ways in which the standardised roles of wife, mother, nurturer and ministering angel, as extensions of that Christian morality, are revised in Paula Rego. I shall also remark upon the resulting effects as regards the gender, class and racial assignation of the roles of victim/corpse and killer/survivor in the work of a painter in whose vision, almost invariably, the results counter expectation.

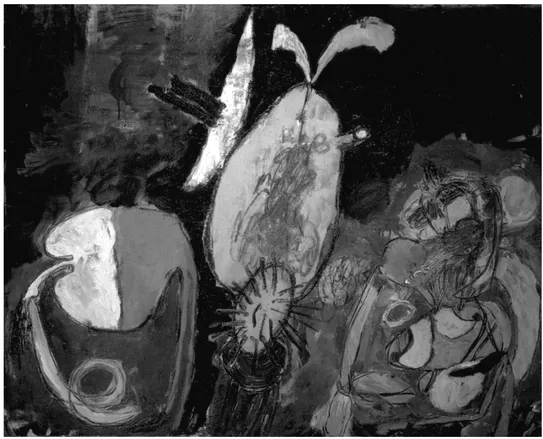

2 Salazar Vomiting the Homeland

I will begin, however, by considering three paintings from the 1960s which, as much by virtue of their titles as by their visual effect (whose semantic accessibility largely depends on those titles), allude to the Salazar political regime which was at its height at the time of their creation. Salazar Vomiting the Homeland (figure 2), When We Used to Have a House in the Country (figure 3) and Iberian Dawn (figure 4) all variously, but with uniform antagonism, address cornerstones of the regime through the person, symbolism and policies of its leader. In Salazar Vomiting the Homeland, the image of the man which Salazar's propaganda machinery cultivated, namely that of the ascetic and monastic hermit wedded to the nation and to his job, is replaced by that of a greedy, vampiric, quasi-cannibalistic spectre disgorging the nation upon which presumably he had previously banqueted.

Paula Rego's painting of i960 begs many questions concerning the regime to which it alludes: why would Salazar wish or need to vomit a motherland with which supposedly he was at one? Which aspects of the motherland are here being ejected? Is the need to do so, whether successful or not, a denunciation of the gap between theory (a motherland and its leader, united in proud isolation) and practice (the dissenting world of realpolitik)? Why does the motherland make its leader sick? Is the relationship, after all, not that of a groom and his willingly submissive bride, but rather that of a virus weakening its host?

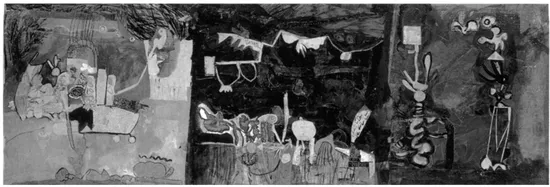

3 When We Used to Have a House in the Country

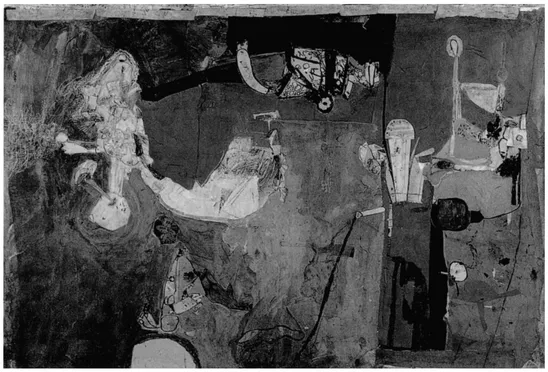

The same ambiguity appears to operate in other works of the same period, including the two mentioned above.

The title of Iberian Dawn, echoing, as it does, quasi-fascist refrains of hyperbolic nationalism ('tomorrow belongs to me'),1 draws out the lampooning figures of various protagonists (the horizontal one on the left, the one in the centre and the large one on the right), each apparently engaged in the same retching behaviour as the Salazar figure in the painting of the preceding year. The balsamic golden tones of half of the picture (signalling the birth of a new day and presumably of a new nation), which take up almost exactly half of the surface area of the picture, contrast with the dismal, sickly grey of the other half. And more crucially, the rising sun of the eponymous Iberian dawn, paradoxically, is located within the grey segment.

The same grey tone is picked up by one critic as being one of the signifying elements in When We Used to Have a House in the Country (Rosengarten, 1997, 44–6) – whose title refers ironically to the colonies as the country cottage of the nation – and operates here as an indictment of the Portuguese colonial undertaking:

[This work] has implicit in it at the level of an absent secondary proposition, an acerbic criticism of Portuguese colonialism. What vision could be more critical of the history of Portuguese colonialism than this figuration, in visceral and depressing colours, giving, in a panoramic sweep of the horizontal scene, the simultaneity of the divergent destinies of coloniser and colonised? (Rosengarten, 1997, 44–6)

In the period spanning the decade from the mid 1980s to the mid 1990s, Paula Rego abandoned the cut-and-paste method of figures drawn, painted, cut out and collaged, moving instead into a more naturalistic, figurative mode. This retained the narrative element of her previous production, even emphasising it because of the greater transparency which the naturalistic method imposed upon meaning. Many of the paintings of this new phase, including the untitled Girl and Dog series (plates 2-8, figures 14-16, 19, 21-22) and most of the paintings on family themes (plates 9-10, figures 23-24, 26-28, 30-32), opted for a foregrounding of the personal over the political, whilst nonetheless retaining, through allusion, a national-political content beyond the family and sexual politics that inform them. On occasion, however, in the course of the 1990s, Rego returned to subjects which gave priority to the political and colonial/race/class concerns of earlier works.

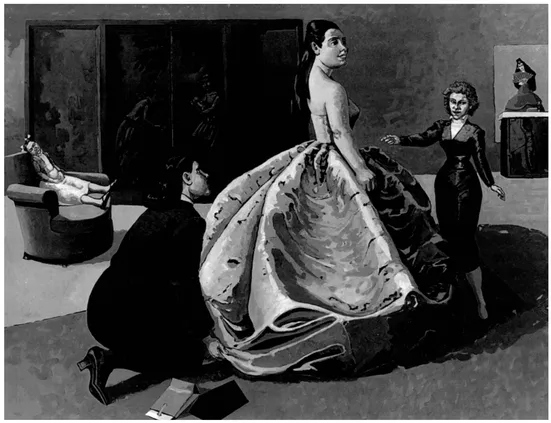

In the first image I shall analyse in detail here, The Fitting (figure 5), a mother witnesses the fitting of her daughter's ball gown by a kneeling seamstress.

The relative scale of the figures, and the strategic play between foreground and background, as so often in Paula Rego, is both perplexing and illuminating. The young daughter looms large in a billowing dress which, it has been suggested, hides many secrets (Rosengarten, 1997, 82). Her mother, although the smallest figure of the three, dominates by her stance of authority, her fiery (demonic) red hair and her quasi-clerical or militaristic attire, similar in some of its associations to that of the godmother in The Bullfighter's Godmother (figure 30), another challenging female figure to be discussed in chapter 2. In the foreground, but disempowered by her subservient posture and class status, is the seamstress.

The interplay of relations is equivocal, and the demarcation of respective positions of power is mutually contradictory: the mother, by virtue of her family and class, here may be the self-evident figure of domestic authority, but her relatively small size cancels this out, up to a point. In a move of further contradictory implications, however, her costume – a female version of either a priest's gown or a soldier's uniform – may signal either the apeing of church and/or state authority, or alternatively the intent to transgress outside the sphere of domestic female rule, and the attempt to occupy a masculine landscape of publicly exercised power. The daughter's status, albeit imposing by virtue of her size, is limited by her youth and presumed filial obedience to the mother, from whom the dress, however, contradictorily and rebelliously hides secrets. She is, additionally, her mother's potential successor in the dynamics of class power that place her over the kneeling seamstress, who, however, confusingly, may be about to pull the (class) rug from under her feet, or to strip the shirt (dress) off her back, in a revolutionary gesture which lays claim to class demanding the rights due to her class. A revolutionary act, therefore, which would also go some way towards explaining the seamstress's disproportionately large stature, in comparison with that of her current mistress.

This atmosphere of potential threat with its blurred demarcations of power is enhanced by the attenuated ghostly figures painted on the wardrobe door, and by the disproportionately small child reclining in a lifeless position in the armchair. And a final puzzle is introduced by the half-visible poster of a Spanish flamenco dancer on the wall behind the wooden counter. The Spanish note introduces ambiguity through the allusion to two possible and mutually contradictory lines of interpretation.

The least challenging is that of the introduction of a schmaltzy, folkloric would-be-exoticism. Spain had been, for ten centuries, the enemy against which Portugal pitted itself in its determination to remain independent. This peninsular neighbour, however, and more to the point, Franco's fascist Spain, was the only destination outside Portugal to which Salazar ever travelled, including the African colonies which he never visited. Spain alone, therefore, and almost for the first time in the history of the two countries which have traditionally existed inimically back to back, enjoyed the privilege of non-foreign status in the eyes of the Portuguese leader, the only territory outside national borders, contact with which was not deemed to defile the 'proudly alone' purity of the Estado Novo. Spanish artifacts, and in particular the gawdy flamenco dolls which were many little Portuguese girls' most treasured possession, were a condoned intrusion of acceptable pluriculturalism within the insularity and homogeneity of censored national life. The flamenco poster, therefore, might on the one hand allude to the regime's acceptance of a controllable foreign intrusion which shored up the unity of Portuguese-Spanish fascist brotherhood.

On the other hand, however, it might signify the operation of a dangerous underground resistance. In the Iberian peninsula, flamenco dancing and culture carry implications which extend beyond the crude tourist diet of tame apolitical exoticism. Flamenco is the music and dance of the Andalusian Gypsies, or Flamencos, and it had its roots in Gypsy, Andalusian, Arabic and Spanish-Jewish folksong. The religious heterodoxy introduced by these origins, some of which have provoked religious persecution since the Middle Ages, are further confirmed by the usual positioning of the practitioners of flamenco (which also included outcast Christians) on the fringes of social acceptability. The themes of flamenco music and dance tend to be those of despair, love, religion and death, the key concept in flamenco being the duende, which is the surrender by the dancer to absolute emotion. Flamenco, therefore, in its untamed version, becomes both the release of the unbridled self and the art form par excellence of the outsider, precisely those elements of society marginalised in Portugal and Spain by a conflation of social, religious and political imperatives. Their interests would have stood in exact antithesis to the emotionally corseted, religiously orthodox and politically oppressive tenets of the Salazar regime.

It is fitting, therefore, that the flamenco poster in this painting, potentially a sign of the dangerous slide away from convention at many levels, should figure marginally, placed at the side, in the background, half-hidden and guillotined along both its horizontal and vertical axes, by the wooden sideboard and the edge of the painting respectively. Its attenuated presence, however, through a typical Rego sleight of hand, is countered by two factors: the eye-catching red of the dress and veil of the dancer; an...