![]()

1 East meets West

Re-presenting the Arab-Islamic world at the nineteenth-century world’s fairs

Debra Hanson

The world’s fairs held in the second half of the nineteenth century were a distinctly modern phenomenon. International in scope, they were the largest and most comprehensive intercultural events staged to that date. As such, they initiated a new awareness within the Western worldview of the transnational connections between nations, peoples, and cultures. This awareness included the Arab-Islamic world, most often constructed in accord with Western interests and the emerging global order they championed. In this regard, the fairs reflected and re-enacted the power dynamic that determined the course of East-West political, military, economic, and cultural interactions of this period, but also provided—within tightly controlled parameters—a forum for displaying the emerging nationalisms of countries outside the Western sphere.

The initial section of this chapter examines the manifestations of these dynamics at the first world’s fair, the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, and its pivotal role in establishing a visual, material, and experiential model of “the East” that served to negate physical distance while confirming cultural difference.1 Through a variety of representational and display strategies that blurred the boundaries of fact and fiction and past and present, the objects, peoples, and cultures of these regions were shaped into an exotic product available for Western consumption. Later expositions, such as those held in Paris (1855, 1867, 1878, 1889, and 1900) and Chicago (1893), adhered to many precedents set in London as they continued to advertise the themes of progress, peace, and prosperity introduced there. With regard to representations of the Arab-Islamic world, however, later fairs considerably modified the 1851 model in accord with the expositions’ physical expansion, wider popular appeal, and concern for financial profits. The concluding portion of the chapter examines these modifications, their cultural impacts, and long-term legacies.

While the late-nineteenth-century expositions were pivotal in the production, display, and marketing of “the East” as a consumable commodity, the attitudes they advanced were not unique to this era. As Edward Said has shown, European attitudes toward the region had long been rooted in “a style of thought based upon… [a] distinction made between ‘the Orient’ and…‘the Occident.’”2 He defines this knowledge-producing discourse, Orientalism, as underpinning the “systematic discipline by which European culture was able to manage…the Orient politically, sociologically, militarily, ideologically, scientifically, and imaginatively during the post-Enlightenment period.”3 As a discourse grounded in assumptions of Western superiority, Orientalism paralleled and supported nineteenth-century colonial expansion in the cultural realm. Timothy Mitchell has demonstrated how the world’s fairs were a part—indeed, the most publically visible part—of this Orientalist network.4 As such, one of their functions was to transform the abstract rhetoric of nationalism, and its promotion of Euro-American superiority, into a visceral reality that could be directly experienced by fairgoers. The spectacles of otherness and exoticism that the fairs provided—at first, simply the novel proximity of foreign artifacts and peoples and later, their incorporation into “villages,” theatrical performances, and other interactive, immersive scenarios—were effective tools for creating this reality. When positioned in relation to foreign peoples and cultures—such as those of Tunisia, to be examined in this chapter—Western nationalisms and the vision of collective progress they created were brought into sharper focus. Dominant populations could thus be defined, and imperialist policies justified, in relation to the “colonized object-worlds” on view.5 The material culture of the fairs—the design of their buildings and grounds, the objects and peoples they displayed, the texts they generated, and the viewing experiences they structured for visitors—thus reflected the political strategies of the host nations who stood at the center of an expanding global order shaped by the prerogatives of imperialism, capitalism, industrialization, and free trade.

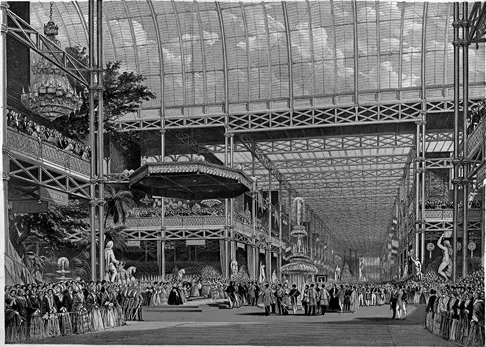

At the expositions, expanding nationalisms were communicated through the wide range of objects on display; fairgoers’ understanding of those objects needed to be shaped and molded accordingly. Prescriptive guidebook commentary played a part in this process, as did the spatial relations constructed within the expositions. At the Great Exhibition of 1851—officially titled “The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations”—all foreign and domestic displays were housed in a single monumental building of glass and iron dubbed the Crystal Palace by Punch, the popular London periodical, due to its reflective glass surfaces (Figure 1.1).6 Neatly dividing the cruciform structure into two sections, its central transept has been described as functioning “like the equator,” an observation typified in a contemporary description of the building’s cartography as “a geographical arrangement which places the showy productions of tropical regions nearest to the transept, and removes to the extremities the less gaudy but more useful industry of colder climates.”7 This symbolic mapping signified a foreign exhibitor’s position relative to the host nation, encouraging visitors to compare the relative merits of each through the products they displayed. While Britain occupied the western half of the Palace with her colonies and dependencies, those entities—such as Malta, Ceylon, and most prominently, India—were assigned spaces closest to the central transept, in proximity to the other “Oriental” countries—Turkey, Tunisia, China, Egypt, and Persia—located just to the east of the transept. Should any viewer misinterpret this arrangement, the text accompanying a lithograph of the transept (Figure 1.1) clarified its meanings:

…a thoughtful observer, standing in the Transept of the Crystal Palace… could embrace the industrial position of the East… In the gorgeous luxury of oriental habits he could trace the germs of the Mahommedan creed so grateful to the senses… he could see the gradually fading image of the Past, whilst in the dazzling display of the contributions of our own land … he could read all the glorious promises which [this nation is] holding out to the world, of a resplendent Future.8

While positioning Britain as modern and progressive, “the East” is cast as its regressive and oppositional “other.” In rationalizing its material culture as a “fading image of the Past,” the writer implies that the resources of these countries—raw materials and manufactures alike—could be better utilized by Western interests, and so offers cultural as well as economic justification for Britain’s imperial ambitions. Within the Crystal Palace, the physical location of national displays enabled the narration as well as the mapping of power dynamics.

Inside the Crystal Palace: Owen Jones and the Arabian Nights

The Crystal Palace that housed the 1851 Exhibition was, first and foremost, a practical solution to the problem of inexpensively constructing a large-scale temporary structure in a short amount of time. Designed by Joseph Paxton, it was built of prefabricated iron and glass components assembled on site in London’s Hyde Park in less than six months.9 While the building’s “form follows function” ethos and foregrounding of industrial materials might at first appear antithetical to any re-presentation of the Arab-Islamic world, this proved not to be the case, as shown by the interior scheme devised by Owen Jones, Superintendent of Works for the 1851 Exhibition. Jones, a key figure in the British design reform movement, devised an interior showcasing the universal design principles that he championed: fitness, proportion, and harmony, to be realized through the use of polychromy, flat pattern, and geometric form, best represented by Islamic structures such as the Alhambra, on which he was an acknowledged expert.10

Seeking to elevate public taste and “bring the building and its contents into perfect harmony,” Jones appropriated visual motifs from a variety of Oriental sources.11 Color was a key element in achieving the harmony he sought, with primary shades of red, blue, and yellow accenting slender iron colonettes, balcony railings, and other structural details (Figure 1.1). A flat, repeating geometric pattern (as seen in the balcony railing above the iron girders) also helped to unify a monumental space filled with a diverse array of objects and people, as did the textile banners, wall coverings, and curtaining devices Jones utilized.12 These also served a practical function by dividing the vast spaces of the Crystal Palace into smaller, more comprehensible increments reminiscent of Eastern bazaars and souqs.13 Initially criticized in some circles, the building’s interior received wide praise once the Exhibition opened and its functionality and appeal were proven; in the six-month duration of the Exhibition in Hyde Park, many came to regard the Crystal Palace as the greatest attraction of the event it housed.

Although the “objects of every form and colour imaginable…far as the eye could reach…and…sixty thousand sons and daughters of Adam, passing and repassing, ceaselessly”14 noted by one visitor surely mediated the legibility of Jones’s design, its innovative use of color and pattern, coupled with the sweeping vistas, intensity of light, and other sensory stimuli, no doubt created an exotic atmosphere that contrasted sharply with the everyday lives of most attendees. Charlotte Brontë’s description of Exhibition as “such a bazaar or fair as Eastern genii might have created…with such a blaze and contrast of colours and marvellous powers of effect” alludes to the connection many visitors made between the Crystal Palace and The Arabian Nights.15 Like the building’s interior, this literary work was a composite drawn from a variety of Oriental sources, locations, and periods that were adapted to suit the tastes of Western audiences.16 In conjunction with popular travel narratives, Orientalist painting, and other period sources, The Arabian Nights’ stories of romance, adventure, and magic reiterated prevailing views of the East as an “imaginative geography” of the ahistorical and the anti-modern, and were widely understood as “depicting a true picture of Arab life and culture, past and present…”17 A satirical letter from one “Mrs. Fitzpuss of Baker Street” published in Punch underscores the extent to which this work of fiction served as a touchstone for viewing the Crystal Palace and its contents:

Since the 1st of May [when the Great Exhibition opened] I’ve driven directly…to the Palace of that great Jin [genie], PAXTON, in Hyde Park, where for hours I’ve done nothing but think myself a great Princess of the Arabian Nights…18

As did Jones’s interior plan, the Punch writer intertwines references to modern industrial design (Paxton) with Eastern tropes and motifs (genii). In later world’s fairs and other cultural production of the period, these fictional tales would persist as a framework for viewing, constructing, and disseminating re-presentations of the Arab-Islamic world in the West, and for articulating the transformative benefits of industrialization, mass production and other forms of capitalist innovation in a period of rapid social and technological change.19

Tunisia at Mid-Century

In 1850, the Middle East, Arabian Peninsula, and parts of North Africa and the Balkan area were ...