- 426 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Supervenience

About this book

The International Research library of Philosophy collects in book form a wide range of important and influential essays in philosophy, drawn predominantly from English language journals. Each volume in the library deals with a field of enquiry which has received significant attention in philosophy in the last 25 years and is edited by a philosopher noted in that field.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

[1]

PHYSICALISM: ONTOLOGY, DETERMINATION, AND REDUCTION*

MATHEMATICAL physics, as the most basic and comprehensive of the sciences, occupies a special position with respect to the over-all scientific framework. In its loosest sense, physicalism is a recognition of this special position. Traditionally, physicalism has taken the form of reductionism—roughly, that all scientific terms can be given explicit definitions in physical terms.1 Of late there has been a growing awareness, however, that reductionism is an unreasonably strong claim.2 Along with this has come recognition that reductionism is to be distinguished from a purely ontological thesis concerning the sorts of entities of which the world is constituted. This separation is important : even if physical reductionism is unwarranted, what may be called “emergence” of higher-order phenomena is allowed for without departing from the physical ontology. (In particular, anti-reductionist arguments are seen as lending no support whatever to Cartesian dualism as an ontological claim.) Moreover, there has been a tendency to suppose that reduction of terminology entails reduction of ontology, but this is mistaken. It is thus necessary to consider just how to state a reasonably precise physicalist ontological position. This is the burden of part I.

Although a purely ontological thesis is a necessary component of physicalism, it is insufficient in that it makes no appeal to the power of physical law. In part ii, we seek to develop principles of physical determination that spell out rather precisely the underlying physicalist intuition that the physical facts determine all the facts. The goal is then to show that these principles do not imply physical reductionism. The main task here is to avoid the effects of the well-known definability theorem of Beth, to which end a natural solution is proposed.

Physicalism, so construed, consists in two sorts of principles, one ontological, the other the principles of physical determination, together compatible with the falsity of reductionism. Yet physicalism without reductionism does not rule out endless lawful connections between higher-level and basic physical sciences.3 Both ontological and determinationist principles have the character of higher-order empirical hypotheses and are not immune from revision. Nor are they intended as final claims, for it is recognized that physical science is a changing and growing body of theory. Nevertheless, these sorts of principles can be adopted at various stages of development to assert the tentative adequacy of a physical basis for ontology and determination.

I

1. Ontology and Reduction. Presystematically, the physicalist ontological position is simply put: “Everything is physical.” However, unless ‘physical’ is spelled out, the claim is hopelessly vague. Yet, as soon as the attempt is made to identify ‘is physical’ with satisfaction of any predicate on some list of clearly physical predicates (drawn, say, from standard physics texts) it is discovered that the simple formula, (∀x) (x satisfies some predicate on the list), fails of its purpose. Unless closure of the list under some fairly complex operations were specified, predicates of ordinary macroscopic objects would not appear, and the claim would be trivially false. Indeed, one seems already forced into the reductionist position of defining—at least in the sense of finding extensional equivalents for—all predicates in terms of the basic list. What started as a bald ontological assertion seems to involve dubious claims as to the defining power of a language. When it is contemplated, moreover, that, no matter how sophisticated the list and the “defining machinery”, there are bound to be entities composed of “randomly selected” parts of other entities which elude description in the physical language, then it is evident that something is wrong with this whole approach.

There is another approach. As a preliminary, it should be stated here that no sharp distinction between physics and mathematics is being presupposed. Since we are interested in physicalism vis-à-vis the mind-body problem and the relations among the sciences, we do not wish any physicalist theses that we formulate to turn on views concerning abstract entities. For the purposes of this discussion we will assume an object language L containing a stock of mathematical-physical predicates, including those which might be drawn from texts concerning elementary particles, field theory, space-time physics, etc.4 as well as identity, the part-whole relation, ‘<’, of the calculus of individuals, and a full stock of mathematical predicates (which, for convenience we may suppose are built up within set theory from ‘ɛ’). The metalanguage in which we work includes L [and enough to express the (referential) semantics of L]. Henceforth, we shall use ‘physics’ to mean “physics plus mathematics” and shall speak indifferently of “physical” or “mathematical-physical” predicates.

Now a thesis that qualifies as ontological physicalism not involving any appeal to the defining power of L (or any language) asserts, roughly, that everything is exhausted—in a sense to be explained—bymathematical-physical entities, where these are specified as anything satisfying any predicate in a list of basic positive physical predicates of L. Such a list might include, e.g., ‘____ is a neutrino’, ‘ ___ is an electromagnetic field’, ‘____ is a four-dimensional manifold’, ‘____ and ____ are related by a force obeying the equations [Einstein’s, say] listed’, etc. There are no doubt many ways of developing such a list, depending on how physical theory is formulated. The fundamental requirement for a basic positive physical predicate at a place is that satisfaction of it at that place constitutes a sufficient condition for being a physical entity, clearly enough to be granted by physicalists and nonphysicalists alike.5 Clearly, negations of primitive predicates of physics do not qualify; hence we say “positive” physical predicates. However, it is clear that certain predicates, even primitives, do not meet the fundamental requirement just stated at any place. For example, to include ‘=’ in the list would beg the question: any nonphysicalist will agree that everything is exhausted by all the entities in the extension of this predicate! The same goes for the part-whole relation ‘<’, and for set membership ‘ɛ’, since what are regarded as among the relata of these predicates depends quite directly on one’s ontological position. Finally, we must exclude predicates of location of the form ‘is at space-time point p’, since it would be question-begging to say that merely having location is sufficient for being a physical object.

Assume, then, that requisite exclusions of this kind have been made and we have a list, Γ, of basic positive physical predicates with the concrete places specified. In terms of Γ we now sketch a physicalist ontology. Since ‘ɛ’ is not in Γ, special provision must be made for mathematical entities. The alternative we favor consists in an iterative set-theoretic hierarchy built on a ground level of concrete physical entities (plus the null set). Since the mathematical objects required by physical science can be developed within set theory, we may concentrate on the members of Γ at their concrete places (where they apply only to objects in space-time). Thus stipulating that

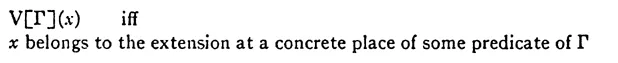

we may apply notions of the calculus of individuals6 to objects x such that V[Γ](x). In particular, where Δ is any set of predicates, it is assumed there is a unique individual that exhausts all objects satisfying V[Δ], that is,

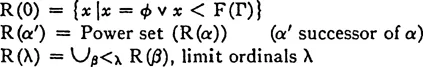

where ‘<’ is the part-whole relation of the calculus of individuals, here understood as “spatiotemporal part.” We designate this individual F(Δ). The hierarchy is defined thus:

These are just like the ranks, def...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Geoffrey Paul Heilman and Frank Wilson Thompson (1975), Thysicalism: Ontology, Determination, and Reduction’, Journal of Philosophy, 72, pp. 551–64

- 2 Simon Blackburn (1985), ‘Supervenience Revisited’, in Ian Hacking (ed.), Exercises in Analysis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 47–67

- 3 Jaegwon Kim (1984), ‘Concepts of Supervenience’, in Jaegwon Kim, Supervenience and Mind, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 53–78

- 4 Jaegwon Kim (1993), ‘Supervenience for Multiple Domains’, in Jaegwon Kim, Supervenience and Mind, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 109–30

- 5 Jaegwon Kim (1993), ‘Postscripts on Supervenience’, in Jaegwon Kim, Supervenience and Mind, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 161–71

- 6 Terence Horgan (1982), ‘Supervenience and Microphysics’, Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 63, pp. 29–443

- 7 Terence Horgan (1993), ‘From Supervenience to Superdupervenience: Meeting the Demands of a Material World’, Mind, 102, pp. 555–86

- 8 Brian P. McLaughlin (1995), ‘Varieties of Supervenience’, in Elias E. Savellos and Ümit D. Yalçin (eds), Supervenience: New Essays, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 16–59

- 9 Robert Stalnaker (1996), ‘Varieties of Supervenience’, Philosophical Perspectives, 10, pp. 221–41

- 10 James C. Klagge (1988), ‘Supervenience: Ontological and Ascriptive’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 66, pp. 441–70

- 11 John F. Post (1995), ‘“Global” Supervenient Determination: Too Permissive?’, in Elias E. Savellos and Ümit D. Yalçin (eds), Supervenience: New Essays, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 73–100

- 12 R. Cranston Pauli and Theodore R. Sider (1992), ‘In Defense of Global Supervenience’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 52, pp. 833–54

- 13 John Bacon (1986), ‘Supervenience, Necessary Coextension, and Reducibility’, Philosophical Studies, 49, pp. 163–76

- 14 James Van Cleve (1990), ‘Supervenience and Closure’, Philosophical Studies, 58, pp. 225–38

- 15 Thomas R. Grimes (1988), ‘The Myth of Supervenience’, Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 69, pp. 152–60

- 16 David Lewis (1986), ‘Humean Supervenience’, Introduction to: Philosophical Papers II, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. ix, para. 3 – xvi line 8

- 17 Barry Loewer (1995), ‘An Argument for Strong Supervenience’, in Elias E. Savellos and Ümit D. Yalçin (eds), Supervenience: New Essays, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 218–25

- 18 David Papineau (1995), ‘Arguments for Supervenience and Physical Realization’, in Elias E. Savellos and Ümit D. Yalçin (eds), Supervenience: New Essays, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 226–43

- 19 Trenton Merricks (1998), ‘Against the Doctrine of Microphysical Supervenience’, Mind, 107, pp. 59–71

- 20 Nick Zangwill (1995), ‘Moral Supervenience’, Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 20, pp. 240–622

- 21 Gregory Currie (1990), ‘Supervenience, Essentialism and Aesthetic Properties’, Philosophical Studies, 58, pp. 243–57

- Name Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Supervenience by Jaegwon Kim in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.