- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Examining international law through the lens of the Middle East, this insightful study demonstrates the qualitatively different manner in which international law is applied in this region of the world. Law is intended to produce a just society, but as it is ultimately a social construct that has travelled through a political process, it cannot be divorced from its relationship to power. The study demonstrates that this understanding shapes the notion, strongly held in the Middle East, that law is little more than a tool of the powerful, used for coercion and oppression. The author considers a number of formative events to demonstrate how the Middle East has become an underclass of the international system wherein law is applied and interpreted selectively, used coercively and, in noticeable situations, simply disregarded. International Law in the Middle East brings various narratives of history to the fore to create a wider arena in which international law can be considered and critiqued.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access International Law in the Middle East by Jean Allain in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & International Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Beyond Positivism: Denial of Kurdish Self-Determination

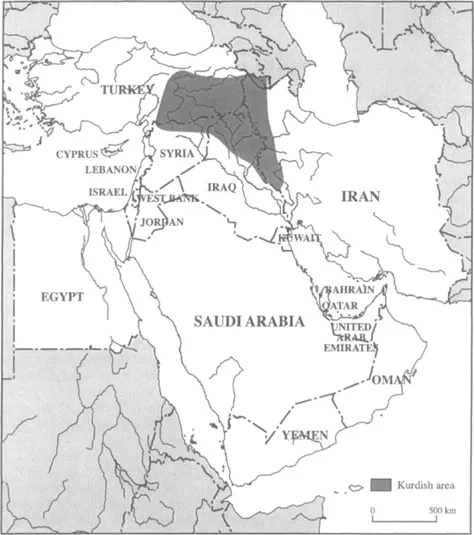

The century-long plight of the Kurdish people, denied not only the ability to establish an independent State, but to gain even a measure of autonomy over their language and culture, is a clear manifestation of the denial of self-determination justly conceived. ‘Kurdistan’, those areas of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, where Kurdish people find themselves in the minority, have had their rights, both individually and collectively, suppressed in an attempt to ensure the consolidation of those existing States. It was estimated in 1996 that there were between twenty-four and twenty-seven million Kurds living in the Middle East. This is more than the individual populations of the following States: Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, or Yemen. After Arabs and Persians, Kurds constitute the largest ethnic group in the region. Nearly half of all Kurds, thirteen million, live in Turkey, where they constitute an estimated one-fifth to one-quarter of that State’s population. The same percentage of Kurds are found living in Iraq, though they amount to over four million people, while in Iran there are approximately six million Kurds, making up about ten percent of that population. Nearly a million more Kurds find themselves in Syria, with smaller populations living in both Armenia and Azerbaijan1.

What makes the claim of the Kurdish self-determination such a strong one, is twofold: first, the pulling of the carpet from beneath the move to establish a Kurdish State in the aftermath of the First World War. Second, the repression of Kurdish identity by the newly created Middle Eastern States which, over the years, has taken various forms: from the denial of cultural rights to genocidal levels of repression. It is this mixture of past failings and present repression that demonstrates the extent to which international law, as applied in the Middle East, is qualitatively different than elsewhere. Despite the fact that the International Court of Justice noted in 1995 that self-determination is ‘one of the essential principles of contemporary international law’2, its scope—as law—is so limited as to render its applicability near to naught. In other words, when examining the content of the legal norm of self-determination it becomes evident, by its limited nature, that it reflects the will of States at the expense of the aspirations of nations, be they defined by a common culture, language, or religion. If self-determination were to be conceptualised in a just manner, it would surely find room to accommodate a people, which today find themselves in the neighbourhood of thirty million strong, to determine for themselves their political association. However, States have established positive international law in such a manner as to ensure that the Statist systems prevails; that self-determination takes place within the Westphalian State system which has, as of yet, been unable to accommodate aspirations of the Kurdish people.

The Kurdish Area

I. Failure of a Kurdish State to Materialise

With the defeat of the Central Powers, the victors of the First World War were in agreement that the ‘Sick Man of Europe’ should be left to die. While it was agreed that the Middle Eastern possessions of the Ottoman Empire should be reconstituted, the Allied Powers struggled to establish a map of the region that took into consideration their varied interests and their ability to impose their conception on the people of the Middle East. The main casualty of the post-First World War settlement and, hence, the modern Middle East, was the failure of a Kurdish State to materialise. This, despite the fact that ‘Kurdistan’ was considered at the Paris Peace Conference as a nominally independent State that should fall under the Mandate system envisioned by the Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations. That no Kurdish State would emerge was a clear indication that the notion of ‘self-determination’, as conceived at the end of the First World War, was little more than political rhetoric which would come a lowly second to the interests of the European Powers3. Yet, this was at variance with the firmly held belief of the then President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, that the concept of self-determination should be the basis upon which a post-War order should be established. In his Fourteen Points speech, outlining the war aims of the United States, Wilson not only spoke of ‘free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims’, but he also outlined his thoughts regarding the region of the world which encapsulated Kurdistan:

Point XII: The Turkish portion of the present Ottoman Empire should be assured a secure sovereignty, but the other nationalities which are now under Turkish rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development, […]4.

It appears that the nascent Kurdish independence movement placed its trust in the Wilsonian conception of self-determination, as was made evident in the pages of the Jin, the official organ of the League of Progress of Kurdistan published in Constantinople from 1918 to 19205. Kamuran Bedir Khan, a leader of the Kurdish movement at the time, wrote in 1918, ‘Whatever the current political changes and no matter the decisions taken, there remains the good humanitarian principles of the famous President of the United States, Mister Wilson. … The truth and justice of these principles, of which the basis has been accepted by the European States, should be paramount over all unjust tendencies and ideas’6. Yet, while Germany accepted the principles expressed in the Fourteen Points speech as a basis of an armistice, as did the Allied Powers, it would come to pass that from this moment onward, the notion of self-determination as it related to Kurdistan would slowly be purged of its content. Various events—foremost amongst which was the retreat of the United States from the international system conceived by its president; the British and French in-fighting over the spoils of war, and finally, the rise of the Kemalists in Turkey—would converge to dissipate the move toward the creation of Kurdistan. Not to be left out of the equation was the lack of a nationalist movement within Kurdistan that could effectively demonstrate a unity of purpose, both in governing the Kurdish region and in articulating its claims internationally to the European Powers.

In January 1918, in the lead-up to the Paris Peace Conference, Great Britain made its war aims known, yet Prime Minister David Lloyd George failed to mention Kurdistan as one of the States that should fall under the mandate system, along with Arabia, Armenia, Mesopotamia, Palestine, and Syria. This oversight, according to Salah Jmor’s doctoral study of the issue was due, in part, to the perception in Europe that Turkish Anatolia was separated on religious lines with Muslim Turks and Kurds having been associated with the genocide of the Christian Armenians. When in Paris, in 1919, the minutes of the meeting of the ‘Council of Ten’ of the Peace Conference, regarding the drafting of the Covenant of the League of Nations, reflect the fact that Prime Minister Lloyd George sought to amend the aims of Great Britain. The minutes read:

He said that he was sorry that he had left out one country in Turkey which ought to have been inserted. He did not realise that it was separate. He thought Mesopotamia or Armenia would cover it, but he was informed that it did not. He referred to Kurdestan [sic], which was between Mesopotamia and Armenia. Therefore, if there was no objection, he proposed to insert the words ‘and Kurdestan’7.

While no objections were heard, when the Covenant of the League of Nations was considered as a whole, the amendment regarding Kurdistan was absent from Article 22 of the French language draft. This, it has been said, was due to the unwillingness of France to allow for the introduction of Kurdistan as a mandate State which it believed would fall under the tutelage of Great Britain, and thus to French geopolitical disadvantage8. When Article 22 of the Covenant was finally accepted, reference to any State, that was to be placed under the League’s mandate system, was omitted.

Although clearly a setback to Great Britain (not to mention the Kurds), Lloyd George persisted in seeking the establishment of a Kurdish State, not for reasons of affinity toward any Kurdish nationalist movement but for reasons of geopolitics. Great Britain saw in the creation of Kurdistan a buffer State between Turkey and Russia on the one hand and Mesopotamia on the other9. While the British were not willing to acknowledge that the Sykes-Picot Agreement was of relevance to the Palestinian mandate, this secret 1916 pact, setting out the spheres of influence of a dismantled Ottoman Empire between France and Great Britain, was very much the basis upon which the Kurdish region of the Middle East was partitioned. As the United States of America slowly withdrew from the post-War peace with the United States Congress unwilling to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, or accept the mandates for either Armenian or Kurdistan, Great Britain was left to fill the void. In its negotiations with France, which transpired throughout 1919–20, Great Britain, unwilling to take on the financial or military burden of acting as the mandatory power of a ‘Greater’ Kurdistan, slowly dismembered it with the aim of retaining its core: the oil rich vilayet (i.e. province) of Mosul. The outcome of these negotiations, which transpired both in London and San Remo, is revealed in the provisions of the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres.

The Treaty of Sèvres, meant to set the peace between the Allied Powers and Turkey, allowed for the possibility of the emergence of a Kurdish State. However, this State was to be a shadow of an ethnically based Kurdistan, as it was to encompass only twenty percent of the territory on which Kurds resided, and was less than a quarter of what had been sought by Kurdish representatives at the Paris Peace Conference10. As neither France nor Great Britain was willing to allow Kurdistan to be attached to the other European State’s mandated territory, it was decided by the Treaty of Sèvres that the territory would be attached to Turkey, despite the supposed war aims of the Allied Forces to free such nationalities from the Ottoman Empire. By virtue of the Peace Agreement, a commission was to draft a scheme for local autonomy for these Kurdish areas; however, if within in a year of the coming into force of the Treaty of Sèvres, the Kurdish people could demonstrate to the League of Nations their wish for independence, Turkey was to oblige. The relevant provisions of the Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Turkey, signed on 10 August 1920, in Sèvres, Fran...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Table of Cases

- List of Maps

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- The Mellan Dialogue

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Beyond Positivism: Denial of Kurdish Self-Determination

- Chapter 2 Imperial Attitude toward the Suez Canal

- Chapter 3 Disregard for International Law in the Evolution toward the Formation of the State of Israel

- Chapter 4 Lack of Enforcement of International Law and the Abandonment of Palestinian Refugees

- Chapter 5 Selective Enforcement of International Law: The Security Council and its Varied Responses to a Decade of Aggression (1980–90)

- Chapter 6 Punitive in extremis: United Nations’ Iraqi Sanctions

- Chapter 7 Internalising the Requirements of International Law: Perpetual States of Emergency in Egypt and Syria

- Chapter 8 A Stream Apart: Peaceful Settlements in the Middle East

- Epilogue

- Appendix 1: 1888 Constantinople Convention

- Appendix 2: l’Entente Cordiale: The 1904 Franco-British Declaration

- Appendix 3: 1956 Sèvres Protocol

- Appendix 4: UN General Assembly Resolution 302 (1948)

- Appendix 5: UN General Assembly Resolution 3314 (1974)

- Appendix 6: UN Security Council Resolution 425 (1978)

- Appendix 7: UN Security Council Resolution 479 (1980)

- Appendix 8: UN Security Council Resolution 508 (1982)

- Appendix 9: UN Security Council Resolution 598 (1987)

- Appendix 10: UN Security Council Resolution 660 (1990)

- Appendix 11: UN Security Council Resolution 661 (1990)

- Appendix 12: UN Security Council Resolution 678 (1990)

- Appendix 13: UN Security Council Resolution 687 (1991)

- Appendix 14: UN Security Council Resolution 688 (1991)

- Appendix 15: UN Security Council Resolution 1483 (2003)

- Bibliographic Note

- Index