![]()

Part 1

Stages in a Life

![]()

1

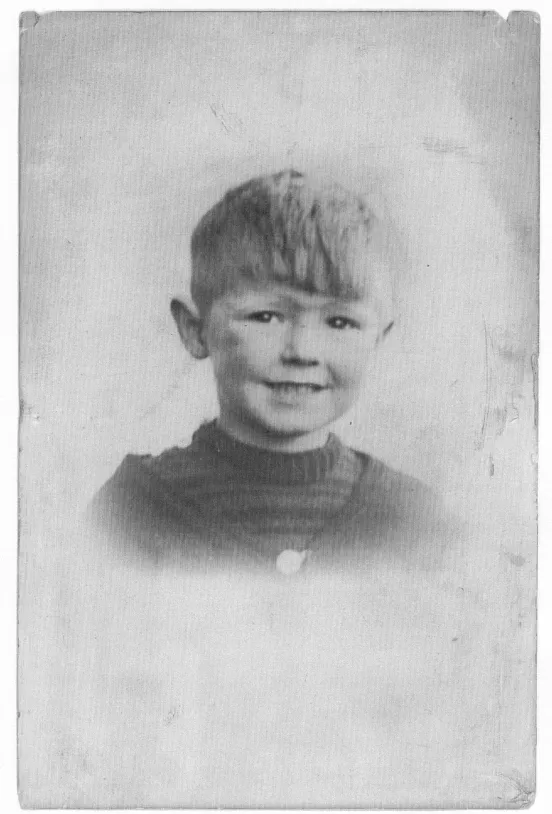

The Child: Dancing for the Woolworth Ladies

He never knew how it started, the dancing business. But then, like so many supposed childhood memories, it only seems half real at a distance. How many were really his own memories and how many were things she had told him so often that he thought he remembered them? But this must be a real one in some way because he could see the dance itself, and she had never told him about that, just that he danced for the ladies. It was a strange little affair: hop skips in a circle, arms outstretched like an ungainly bird trying to take off; then hands above the head, palms together, and twirl and twirl and twirl until dizzy; then a dreamy swinging lurch in a circle in the other direction. A bizarre kind of bird dance to be sure. Perhaps he had been inspired by watching the plovers on the moors, with their pathetic attempts to feign wing injury, to lead him away from their nests. But surely that came later, when he was older? Dancing for the biscuit-counter ladies started when he was about two years old. But he would have already been to the moors by then. Not alone. They would have been with him. Alone came later. But wherever it came from, the dance was a hit. The Woolworth Ladies applauded and cooed, and gave him gingersnaps and biscuits with cream-filled centers: little luxuries that were way beyond the penny bag of broken arrowroots they came to get. He always saved the luxuries and gave them to her after they left Woolworth’s, and then they shared them. At least that’s what she told him. He was such a thoughtful toddler. Again in retrospect he wondered. A normal toddler would surely have scoffed the lot at the first chance. Two-year-olds are not known for delayed gratification on this scale. But then, was he a normal toddler?

For a start he should never have been born. He doesn’t of course remember his birth except through her stories. But there again in dreams he finds himself in a giant water sack suddenly exposed to the light and loud sounds. He kicks to get free and can’t and chokes and wakes up screaming. If this is a real memory, did they hear that fetal scream? Did they see him thrashing like a captured fish in a plastic bag, his gills working overtime, until he was pushed back into the dark and the quiet? Evidently it’s written up in the medical journals of the time. But then there was no television and it didn’t make the headlines. The doctors had told her that if the appendix was to be successfully removed, the baby should really be removed first. They could try to move the womb out, take out the appendix, and then put the womb back, but the chances of normal birth after that were slim, and there would be no more children. The doctors discussed this with her, and with the father; together they decided to try to keep the baby. The doctors were against it, but it looked like a last chance anyway and the fateful decision was taken. He was hauled out thrust back and sown up like the contents of a haggis. During all this time she had barely eaten and couldn’t eat much afterwards. He was probably only saved because when born he was so tiny (less than three pounds) that he came out easily. And after all, he’d had a kind of practice. Talk about the twice born. What do they know?

But he shouldn’t really have been born nor should he have survived the double pneumonia of his first year. Tiny baby with the tiny bones: they bathed him in a salad bowl; he slept in a padded shoebox. Some lady doctor with sound common sense told her not to wean him at the fashionably early time but keep him on the breast. There he huddled, shivered and survived. Early on he beat the odds. The rest was all borrowed time. And he was the precious child, the only child, literally the unique one. The burden was to be all on him. But whatever the fright of the double birth might have done, he was henceforward held tight in a cocoon of love that had him live and dance and roam and never forget that he was a miracle. It’s hard being a miracle; but he seemed to be succeeding with the Woolworth ladies at least. He had the gingersnaps to prove it.

A penny bag of broken arrowroot biscuits. Yes. That’s a memory. Biscuits were sold loose then, and if you went at the end of the day they’d sell off the broken ones for next to nothing. It was part of the survival thing which at the time he never noticed but parts of which were graphic enough in memory. He had one absolutely genuine memory; all his own. He knew which these were because they were things the adults didn’t know about and so they must be his and not just memories created by the praise poems she sang about him to the relatives and neighbors and friends and anyone who would listen. Here is the memory as he told it to them:

He was on a broad pavement with big stone squares. He was watching other small children play marbles or hop scotch. In the background was a large redbrick building with long grimy windows, and lined against the wall were men, lots of men, in cloth caps and waistcoats, smoking and talking. The men were laughing and occasionally pointing at the children. The men seemed so big and the voices so deep, and they seemed far away although they were really only a few steps. And for the first time he had the feeling: they knew something he didn’t know. The grownups knew something and that thing made them different, like things from another world. Once he was a grownup he would know what that was and he would have that confident laugh, that authority with the world he never felt. No longer would he have to please the Woolworth ladies, to please her, because he would know the secret and he would have the power. He didn’t tell them about this feeling. They wouldn’t have understood and he couldn’t have articulated it. But he was sure this was the first time. But where was he?

It was settled. There was only one place he could be said his father. On Saturday mornings when the men went to the labor exchange to collect the dole, they often took the children with them to play together on the wide pavement before they went in. The mothers liked this arrangement because it meant the men would come back home with the children and the dole intact and not take it off to the pub or the dog track or wherever. Not that his father would ever have done that she hastened to interject always, but some would and we knew who they were. It was bad enough only having eighteen shillings a week of which nine went on rent. How could they think to go off drinking and gambling? Man may not live by bread alone, but he’d better start with it or he’d not be around to do any of the other things. He heard and was proud of his father who was not like other men. But it was a genuine memory, and his own, and his earliest, and he must have been almost three—about the time of the Woolworth ballet.

Of course he didn’t dance for the biscuits. They were buying the arrowroots anyway, and the other luxuries were only a tiny treat; they were not needed. He danced to please her because she was proud of anything he did, and she was anxious to have her pride confirmed. The child rescued from death was precocious, she knew that. But she was not well educated, having spent most of her young years in a TB sanitarium where they saw she had the basic three Rs and drawing, and where she became an avid reader. But her knowledge of the world was limited and she needed this outside confirmation. The Woolworth ladies were a small part of this, but their applause and cries of amazement were a contribution richly rewarding to her. He didn’t usually sing for them, but he sang for the uncles. Again the uncles are a dim memory if a memory at all—and the hordes of cousins long forgotten. He never bothered much with the cousins. He was always looking to the adults. Always looking for the secret. The uncles knew hundreds of songs, as his father did, many of them World War I songs. He could do a fair version of Roses of Picardy before he had any idea what the words meant—except that they were sad.

The roses will fade with the summertime

And although we are far far apart

There is one rose that blooms still in Picardy

It’s the rose that I keep in my heart

He knew to throw out his hand at the end and hold the last note because that is what uncle George did and it always got lots of applause. Nothing of course compared with the applause he got: he’d be another John McCormack, they said. But wasn’t that the point. The uncles are a blur of jolly red faces with their perpetual waistcoats and watch chains and the smell of snuff, tobacco, and wet wool that always hung around them. They all worked in the wool mills and the smell clung. His father had no work at the time, hence the dole queue. He smelled of country things: wet grass, wood smoke, cheap cigarette tobacco (Woodbines in packs of five), chickens, and manure. They lived not in the town, but in the nearby country villages, where they tapped into the rural economy and the bounty of nature: rabbits and pigeons and the produce of the hedgerows. Now he did remember the big woven baskets and collecting berries and how the thorns and spines hurt his fingers. There were the wonderful smells afterwards in the kitchen—smells of blueberry and elderberry and raspberry and wild strawberry, and bilberry picked from the heather, all being made into jams and preserves. There was the wild thyme and mint and watercress and acres of free rhubarb which grew like a weed, and even the tender shoots of nettles boiled or made into delicious drinks with dandelion leaves—the smells of sugar and yeast and fermentation. It would always pain him to have to pay for any of these things. God intended them as free: you just reached out and took them. You didn’t need to dance for these. Rabbit and pigeon made delicious pies, the hens gave eggs, and once they were old they gave themselves to be simmered for hours, with vegetables from the allotment, to get them tender.

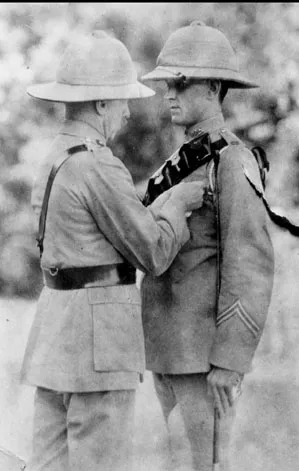

He remembered sitting with Grandpa (an honorary title—both his real grandfathers were dead from the aftereffects of battlefield gas), cutting up old cabbages to throw to the hens. He remembered the disputes this caused: the first time he heard them quarreling. She said grandpa overstuffed the hens, sitting there day in and day out cutting up food and throwing it to them, and they couldn’t lay properly. The father said it was all the old man had to do and they shouldn’t spoil his pleasure. She said he didn’t have to feed the family or he would care more. The father, as usual, went silent, never having many words except when singing, or occasionally telling his old army stories. She didn’t care for these, but the boy was fascinated. It was another world—of desert and dry hills and scorching suns and wild men in turbans charging with swords, and heroic deeds of attack and retreat, and long days of boredom when the main activity was going out on the veranda to kick the punka wallah who had fallen asleep and let the fans slow to a halt. Then those terrible sad days on some burnt hillside at sunset where they stood to attention round a grave and the bugler played the last post, which his father imitated, making the unbearable weeping bugle notes. And days of languid sunny pleasure to see the Taj Mahal and the Vale of Kashmir.

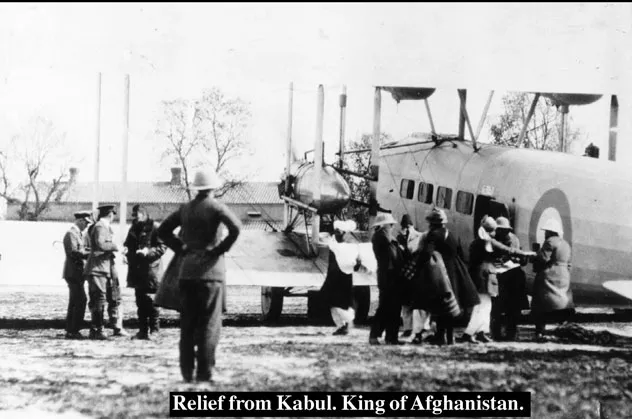

He didn’t realize at the time how desperate the father was for this life which was all the quiet man cared about; how restricted and imprisoned the man felt in this little Pennine village hanging on to the edge of the cliff above the town. How his head swarmed with raging Pathans and laughing pals and foolish officers and funny servants and cricket on the local maharaja’s personal cricket field. But together they poured over the albums of tiny box brownie prints brought back and already fading: the rambling Red Fort at Agra, the unreal beauty of the Taj Mahal, the mythical Vale of Kashmir, the sinister Khyber Pass; groups of soldiers, grinning servants in dhotis, brilliant Sikh horsemen, and gallant little Gurkhas with their heavy knives. Even the King of Afghanistan escaping by plane from his fractious country stirred into rebellion by Russian villainy: Amantullah fleeing Nadir Khan on the first occasion in military history when troops were airlifted. These were vast lives the adults lead. The quiet man had helped to rescue a King.

It was all given up to come back and marry her. They argued about that too. He should have stayed in the army, she said; it was security, a house in the married quarters, status even. But she didn’t realize that the army as such was not the thing: it was the army in India. Away from that he didn’t seem to care what he did, and was as happy doing nothing as working. She had lied to her employer—a professor of Economics at Leeds University, for whose children (Bunty and Tony—both girls) she was the nanny. The professor and his lady, who had her absolute devotion, asked if her young man had a job. They were kind people and concerned for her, so she said he had; but he was to be more than two years without one. They had a shilling less a week than Frank McCourt’s parents, and paid three shillings more in rent. But there was no sense of blinding poverty even though they were unquestionably poor. For a start, the father did not spend the pitiful few shillings on drink. And they were in the country with the vegetables and the chickens. They gathered those free goods of nature that stayed so vividly in the nasal memory. They cheated, as did every one on the dole who could get away with it. If you revealed any casual income the “means test” would make you sell “unnecessary furniture.” The father worked a few hours a week for the farmer where she worked part-time as a cook—and the farmer threw in some meals, butter and vegetables, and all the rabbits and pigeons he could take on the farm lands. Someone ratted on them however. And for the first time he saw her anger—as much with the father for being so stoical about it as with the perpetrator. We were bound to get caught sooner or later, he said. But for her it was the unmitigated evil of the snake who told the authorities. He was frightened at the expression of her hate; he went outside and stayed there a long time with Grandpa and the chickens.

People often didn’t like her. She had airs and pretensions above her station. She, unlike them, had worked in middle-class houses and absorbed middle-class values. (But what does a professor do, mummy? Very clever things. Oh.) She also had plenty of middle-class relatives and they remained her model of correct and decent behavior, not the feckless working class among whom she was unhappily trapped, and who could have been avoided if only the father had stayed in the army instead of just the reserves. But the reserve money—thirteen pounds and thirteen shillings a year, paid quarterly—made all the difference. It was the slight edge that gave them a holiday at Blackpool or Morcambe or Scarborough when the others, with their over-large families—another subject of indignant scorn—couldn’t afford it. But she never compromised. They had high tea and read Winnie the Pooh and listened to suitable programs on Children’s Hour and saw Shirley Temple movies. They went to church on Sunday mornings with all new clothes for Easter Sunday and always said please and thank you (it would never have occurred to him to do otherwise.) He wore the fashionable little Teddy Bear coats and hats, even if they were either home made from patterns or bought at the cut-price store. He didn’t get to play with the grubby children who didn’t do these things—even the cousins who fell below par. So she was not liked, but she didn’t care. She knew what the nice people did and she emulated it as best she could, especially after the father found work—in the wool mill of course. To work at all in those days was status.

She was uneasy about the father’s passion for Rugby League, but sensible enough to know that it was a cheap and harmless pleasure—not like the pub or the dog track, and also could be made a family “outing” with sandwiches and thermos flasks of hot dark tea. Cricket especially was positively encouraged for these reasons. So every Saturday was a sports expedition. How could they have known that it was to lead to the little miracle’s first public triumph—a triumph so great that any subsequent successes were always measured against it. “Why, it’s just like Wembley all over again.” And he would agree, but again without knowing if it was his memory or theirs. Of course, they would say, you must, absolutely must remember it. But he had heard the story and looked at the photographs so many times, that how much of it was really his he did not know. The band part he thought he remembered. That much was his. But he had really no idea what was happening, the little two-year old miracle. A lot of noise, a lot of people, an inordinate amount of attention, more than usual, and him performing at the top of his lungs and marching form, and the applause. Yes, perhaps he remembered.

For a start the team managed its own miracle. The Cinderella of the league, given no chance at all, produced a back called Joey after whom his budgerigar was named. “Joey, Joey, poor Joey!” it repeated in endless imbecility. And Joey on the field repeated feats of derring-do which landed the team—otherwise rank outsiders—in the league cup final. This was always played in London at Wembley Stadium even though the game was confined to the northern counties. The excuse was to publicize the professional game in the south (where the amateur Rugby Union held snobbish sway) but the real reason was to give twenty thousand northerners a chance for a cheap trip to the capital. The processions of coaches started south at ungodly hours of the morning and the barbarian hordes poured in. (They were good-natured and nonviolent hordes though in those days—the midst of a depression. Something frightening has happened since then.) For the occasion she had knitted (she knitted practically everything he wore) a blue and white stocking cap, a blue and white scarf, and blue and white mittens. They had blue and white scarves too, but he was the centerpiece with his long blue and white trumpet. The team, being cheered as it boarded the train for the momentous journey south several days earlier, spotted him in the crowd of supporters, adopted him as the team mascot, had their photo taken with him by the local press. The next day it happened. He was on the front page: “Keighley’s Youngest Supporter Ready For Wembley.” Sitting on his father’s arm tooting the trumpet boldly at the crowd. The photo was mounted on a card and all the team signed it. She still has it.

That would have been enough, God knows, but once on the scene they had seats at the front and he went out on the field and marched up and down on the sideline blowing his trumpet for the crowd. The marching band was passing. Breathless hush. The bandmaster comes over and asks if he can borrow “the little fellow.” The father wants to protest, goes red in the face with embarrassment; this is “making a fuss” it is “calling attention to yourself”—the greatest sin of all. But protesting would call even more attention, so it is dropped. Hand in hand the little trumpeter goes fearlessly (what should he fear, he is the miracle boy) to the head of the band, and marches, trumpet a-tooting all around the huge field to the wild applause of a hundred thousand people. Again, it should have been enough, but back home, at the next Shirley Temple film, on came the Movietone News (or was it Pathé?) and there it was. She leapt to her feet in real astonishment and pointed and all the cinema saw. Movietone had chosen to feature this event as much as the game itself. There he was, marching on the newsreel for all the world to see. The team lost the game, of course. But it was a miracle they were even at it. Miracles seek each other out it seems. The rest of his life could only be an anticlimax. But more for them than him. For it was their event really. If he doesn’t really remember it at all, in what sense is it his? The trumpet he had for years. It disappeared somewhere in the wartime travels. It was taken out like a Plains Indian sacred pipe and the great deeds were recited. He thought about that trumpet a lot and about what you got for blowing away at it and pleasing the adults even if you didn’t know what their secret was and what they really wanted. Keep blowing, keep marching, keep you chin up and smile and do the things for the adults that get you chocolate biscuits and two minutes on Movietone; you will find that secret out.

London had been decorated for the coronation of the new King. The previous one was not mentioned, banished from conversation for reasons that were part of that great adult secret. All the fath...