![]()

Section 1

Women’s Authorship and Hollywood Genres

![]()

1 Performance and Gender Politics in Mary Harron’s Female Celebrity Anti-Biopics

Linda Badley

Best known for her 2000 adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ notorious (and reputedly impossible-to-film) serial killer novel American Psycho (United States, 1991) and described in The Guardian in 2009 as one of the film industry’s ‘few high profile female directors’ (Bussman 2009), Canadian-American independent filmmaker Mary Harron is a risk-taker. Although rarely identified as feminist, her body of work, which spans the Lifetime original movie as well as the Sundance/Indiewood circuit, reveals her real centre of interest: reclaiming the histories of ‘problematic’ women. In this endeavour, which is implicitly feminist and queer if not ideological in stance, she favours ‘low’, ostensibly ‘male’ exploitation genres such as true crime, horror and pornography, as well as the celebrity biopic.1 One reason may be that these genres are consistently marketable, which is crucial for a female filmmaker who tells stories about women. Another is that Harron is ‘attracted to things that have stigmas’ and ‘the forms that people look down on’, as she said in an interview in 2013. She continued, ‘People look down on biopics – my first film [I Shot Andy Warhol (United Kingdom/United States, 1995)] was a biopic. […] American Psycho is a kind of slasher movie, one of the most despised forms. And people [look down on] melodrama,’ adding that genres like female melodrama, specifically, have ‘energy’ (in Sunderland 2013).

This chapter highlights Harron’s uses of exploitation or ‘sensational’ genre references in interventionist biopics about ‘problematic’, misunderstood or renegade women who became notoriously larger than life within specific period and media settings: pinup queen/porn star Bettie Page in the 1950s; dyke feminist activist, SCUM Manifesto author and (attempted) Andy Warhol assassin Valerie Solanas in the 1960s; and model/actress/reality star Anna Nicole Smith in the 1990s–2000s. Through such stigmatised topics and forms, paradoxically, Harron’s feminist authorship is articulated, although it is by no means simple and remains aloof from ideology or solidarity with organised feminism. ‘Without feminism I would not be making movies,’ she told Dina Gachman in 2013, meaning that feminism made her career as a female feature filmmaker possible, that she views herself as a product of a culture in which feminism figured centrally, and that her films consequently participate in feminist discourse. While generationally a product of second-wave feminism, whose concerns with the male gaze and female objectification have dominated psychoanalytic feminist film theory, Harron’s perspective is socio-cultural. Her practice, supported by her comments in interviews, rejects the popular psychology associated with therapy culture; it instead sustains a postmodern understanding of the self as a social construct and a Foucauldian view of mores and sexuality as culturally scripted, while emphasising performativity. In short, her practice moves beyond the early feminist theoretical concern with spectatorship to explore how these women made themselves seen and heard within specific cultural contexts.

Stigma, Genre, Gender and Authorship

In the words of Dennis Bingham in his definitive study of the genre, the biopic is ‘A Respectable Genre of Very Low Repute’ (2010: 3) – ‘low’ as in ‘middlebrow’, ‘tedious, pedestrian, and fraudulent’ (2010: 11), and denigrated in much the same way as the ‘woman’s picture’. As biopics about women whose behaviour has been deemed inappropriate, I Shot Andy Warhol, The Notorious Bettie Page (United States, 2005) and Anna Nicole (United States, 2013) belong to an even more suspect subgroup, the ‘biography of someone undeserving’ (a.k.a. ‘BOSUD’) (Bingham 2010: 18). Imbued with postmodern meta-awareness, the BOSUD becomes the ‘anti-biopic’, a subversion of the ‘Great Man’ genre norm, which ‘mocks the very notions of heroes and fame in a culture based on consumerism and celebrity rather than high culture values’ – and of which Man on the Moon (Miloš Forman, United States, 1999) and Ed Wood (Tim Burton, United States, 1994) are prime examples (Bingham 2010: 18). Harron’s biographies of disreputable women both fit and fail to fit into this subgenre. Commingling tonalities and flirting with exploitation genres such as crime, pornography and reality television, their satire is edgy and pro-woman.

Harron also figures in what Bingham describes as a contemporary transition from ‘a producer’s genre to an auteurist director’s genre’ (2010: 18) associated with Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, Oliver Stone and Sofia Coppola, whose biopics are personal or political projects inviting discussion and controversy. Essential to Harron’s authorship is her transnational perspective: although she lives and works in New York City, she was born in Canada and educated at Oxford, and she worked as a music journalist during the Warhol and punk eras in London and New York, where she wrote for PUNK Magazine and directed television music documentaries. ‘Mostly I’m just not American,’ she explained to Anisse Gross of The Believer (2014). Her approach – that of a keenly interested and observant outsider with an insider’s perspective – stems from her journalistic experience: ‘Maybe because I started out researching documentaries, I’ve always been interested in a person in history, in their time. I can’t separate those, particularly with women. Women in the twentieth century are astonishing, how much their lives changed’ (in Durbin 2006). Her films have consequently been dismissed by some as ‘flat’ or lacking in psychological or emotional depth, for downplaying victimisation and causality, or for sending mixed or ambiguous messages, all of which she intends.

Harron’s practice is consistent with Foucault’s understanding of discursive technologies of the self (as a creation and recreation of ‘the individual as an acting subject within history’ [Staiger 2003: 50]) and Judith Butler’s concept of performative agency in Bodies that Matter (1993), which is

directly counter to any notion of a voluntarist subject who exists quite apart from the regulatory norms she or he opposes. The paradox of subjectivization […] is precisely that the subject who would resist such norms is itself enabled, if not produced, by such norms. Although this constitutive constraint does not foreclose the possibility of agency, it does locate agency as a reiterative or rearticulatory practice, immanent to power, and not a relation of external opposition to power.

(Butler 1993: 15)

As Janet Staiger clarifies, ‘rebellious or resistant authorship’ should be understood as ‘a kind of citation with the performative outcome of asserting agency within the normative’ (2003: 51). This approach makes sense of Harron’s representations of her subjects as self-authorising performances. Rather than seeking out the ‘inner’ or ‘real’ Valerie Solanas, Bettie Page or Vickie Lynn Hogan/Anna Nicole Smith, her biopics explore their protagonists’ historical construction and performative agency as located within that context. In the performative sense, then, there is a clear correspondence between their ‘rebellions’ and Harron’s renegade authorship.

Much as Harron seeks recognition through disreputable genres, these three women, who were products of escalating mass media dissemination, sought fame in unconventional, disreputable ways. Strongly self-reflexive, these biopics explore how their subjects’ lives were shaped by the media cultures of their respective eras even as their performances helped shape the latter: Solanas and the Warhol era; Page and the pin-up/pornography industry; Anna Nicole and the rise of celebrity culture and reality television (that has led to today’s era of self-promoting social media). As Harron portrays these women, their creativity is channelled into sometimes grotesque, always powerful performances that, constructed within particular social norms and cultural contexts, altered those same norms and contexts, contributing to change.

Authorship and I Shot Andy Warhol: Performing SCUM

An evocation of the Warhol era from the perspective of his would-be assassin, the radical lesbian feminist author of the SCUM Manifesto (Society for Cutting Up Men), I Shot Andy Warhol lived up to the bravado of its title. The publicity poster featured Valerie Solanas’ (Lili Taylor’s) head superimposed onto a variation on Warhol’s famous silk screen triple image of a wide-legged, gun-toting Elvis Presley. It was arguably the film rather than the 1968 shooting of Warhol, a minor ripple in a year of assassinations, that gave Solanas ‘a lasting place in the cultural imaginary’ (Harding 2010: 144). The project began with her journalistic investigation of great avant-garde artists, ‘Warhol, Pollock: all serious, revered people in the canon’ (in Gross 2014), before Harron discovered the SCUM Manifesto in what she describes as a ‘cataclysmic experience’ that ‘completely changed [her] perspective’ (Gross 2014). Selling a ‘straight’, BBC-style biopic on Solanas would have necessitated featuring Warhol, so she switched to an independent ‘reverse-engineering documentary’ focusing on ‘the least important person’ in the story (Gross 2014), deconstructing the ‘Great Man’ film about a visionary overcoming obstacles to the realisation of his world-shaking idea (Bingham 2010: 7). As the postmodern artist in an age of mechanical reproduction – whose Factory replicated pop art celebrity portraits that dispersed their subjects’ aura – Warhol’s legendary passivity (perfectly embodied by Jared Harris: thin, pale, androgynous, laconic and soporific, with his platinum wig askew) already subverted the notion of the Artist as Great Man. By contrast, Taylor’s Solanas is twitchy, explosive and political.

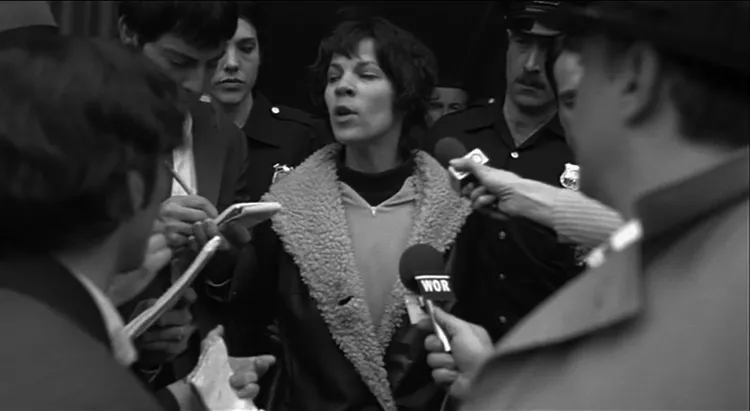

Harron frames the film with Valerie’s shooting of Andy Warhol followed by her calm surrender to the police, leaving open the obvious question: Why did she shoot Warhol? Like Citizen Kane’s rosebud, this question supplies the classic biopic’s pretext: for looking back, by way of a court psychologist’s testimony, to her childhood and circling back chronologically to the shooting. Like the real Valerie, however, Harron subverts this convention by leaving the central question – why did she shoot Warhol? – unanswered. Interrogated by reporters (Figure 1.1), Taylor declines to ‘go into that’, adding, ‘Read the SCUM Manifesto. Then you’ll know what I am.’ Refusing to reduce her either to a case study or an ideology, Harron diverts attention from psychological causation to what first drew her to the project: the context of the 1960s avant-garde and the (mad, ‘inappropriately’ feminist) brilliance of Solanas’ writings.

Moving from interrogation scenes to a review of Valerie’s past, a series of flashbacks whimsically complexify or deflect the ‘official’ record. When the police ask where she is from, Valerie says, ‘The river,’ and the film cuts to faded colour Super-8 ‘home movie’ images of a child playing on the New Jersey shore. Then a psychologist reviews the 28-year-old ‘patient’s’ history, signalling the biopic formula in which causation leads to a diagnosis. In a professional tone, she describes the patient’s childhood as ‘pitiful’, with ‘parental conflict, sexual molestation by her father and separation from her home’; meanwhile the beach footage continues with Valerie looking intently into the camera. ‘By the age of thirteen,’ the psychologist goes on, ‘she [had] had many sexual experiences,’ and at boarding school had her first ‘homosexual’ experience (omitting Solanas’ teenage pregnancy) (Fahs 2014). The psychologist’s case study is perfunctory and at odds with what comes next: a dramatised sequence in which Valerie, described in a recommendation letter from her high school principal as ‘an exceptionally bright girl with lots of courage and determination’, is shown working on an experiment with rats and chromosomes. Next, employed on the school newspaper and asked to respond to a letter from a fraternity representative about the etiquette of wearing corsages for ‘casual affairs’ as well as formal ones, she comments deadpan, ‘An earth-shattering dilemma,’ and writes ‘FUCK YOU’ across it. In another sequence, she flippantly answers a word-association test administered by an attractive female student while caressing the student’s leg with her foot. Valerie ‘completely supported herself’, the psychiatrist’s voiceover continues, through her four years at the University of Maryland, ‘through prostitution’, graduating with As in her (psychology) major. The dramatisations complicate any simple conclusion that Solanas’ ‘pitiful’ childhood and adolescence inevitably led to the shooting or a diagnosis of mental incompetence. Throughout, Valerie’s wit, intelligence and refusal to suffer fools (or psychological tools) trump attempts to categorise her.

While historicising Solanas’ life, actions and rhetoric, the film conveys her paradoxical disconnection from any group, movement or ideology. The contradictions in her stance – which biographer Breanne Fahs sums up in terms of ‘prostitute, activist, self-published writer, mental institution patient, performance artist, lesbian, anti-establishment figure’ (2008: 596) – placed her both inside and beyond the pale of Warhol’s Factory ‘freaks’ who deem Up Your Ass, the play she wants Warhol to produce, too ‘dirty’. She presents as a self-described ‘butch dyke’, but her sexuality defies labels: she despises men officially but engages in prostitution and has casual sex with left-wing colleagues, male and female alike (usually in exchange for something). As in the Manifesto, she arrives at a defiant asexuality as the ideal radical feminist stance. In this respect, she is more like Warhol than otherwise. At one of the Factory’s orgiastic parties, Valerie and Andy are slumped uneasily on either end of a couch. ‘Sex is really nothing, isn’t it,’ Andy comments laconically; Valerie recites from the Manifesto, ‘Sex is […] a solitary experience, non-creative, a gross waste of time,’ a drive that females can easily ‘condition away’.Refusing to identify as a feminist, although Ti-Grace Atkinson called her ‘the first outstanding champion of women’s rights’ and Florence Kennedy one of the movement’s ‘most important spokeswomen’ (in Fahs 2008: 396), she has only contempt for middle-class female academics or civil disobedience. ‘Bitch. Slave,’ she mutters while pacing and watching the Miss America Pageant on television. When the screen is taken over by protesting feminists, an incredulous Valerie raves, ‘These women got everything from me. […] I should be there.’ Earlier in the film, she dedicates Up Your Ass to herself, singling out her own ‘exquisite’ typing for special mention. In an era of radical collectives and movements that also birthed the auteur theory, Solanas regarded authorship as a singular, suffering, heroic act, and the film depicts her typing in cramped, isolated quarters.

Warhol’s Factory epitomised the rise of image-based media culture, commodity fetishism and the obsolescence of print into which Solanas and her manifesto vanished (Heller 2008). Noting this, James Harding claims that Harron undercuts the political significance of Valerie’s violence for avant-garde practice by representing it as a bid for a Warholesque ‘fifteen minutes of fame’ (2010: 155). But he overlooks the film’s foregrounding of Solanas’ performance of textual authorship, which Harron politicises, appropriating Brechtian and Godardian disruptions to the narrative – through shifts in film stock, talking heads and images of banging typewriters that stage the (archaic) black-and-white print medium as performance art. Partly a period piece dominated by the eye-popping colours of the Warhol aesthetic, the film is interrupted by seven black-and-white sequences of Taylor against a white background – the blank setting taken from Warhol’s screen tests – reading from her text (Figure 1.2). The script specifies that the tone of these readings is ‘ironic, controlled, logical, articulate’ (Harron and Minahan 1995: 26); it compels simultaneously bemused and deadly serious attention, as per the opening lines:

‘Life’ in this ‘society’ being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of ‘society’ being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and eliminate the male sex.

Elsewhere, the words appear on ...