- 252 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Urbanization in Post-Apartheid South Africa

About this book

Originally published in 1990, Urbanization in Post-Apartheid South Africa examines the democratic future of South Africa in the context of policy options and constraints. The book looks at the issue of South Africa's future including access to land and housing, marked regional differences in well-being, large peri-urban settlements arising around all major towns, and racial inequalities in access to farming land. The book will be of interest to students of urbanization, geography, economics and planning and African studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Urbanization in Post-Apartheid South Africa by Richard Tomlinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

My primary aim in writing this book is to promote debate about the urbanization policies appropriate to a democratic South Africa. In attempting this, I address three prominent urbanization issues:

● the housing shortage, accentuated by rapid urban growth;

● the desirability and feasibility of diverting economic and population growth from the Pretoria-Witwatersrand-Vereeniging (PWV) region; and

● the fostering of development in the rural areas in order to reduce pressures towards rural-urban migration.

The last issue includes an examination of the effects of redistributing white farms and an assessment of how to respond to the growth of towns in the ‘homelands’.

This enterprise was conceived in 1985 when the intensity of the liberation struggle caused many to begin to question more deeply the nature of the post-apartheid future.1 However, the imminence of majority rule, so strongly felt then, has since receded – there is now widespread acceptance that unless the apartheid government decides that it is advantageous to negotiate, it cannot be dislodged soon. Yet, in a contradictory fashion, the restrictions imposed early in 1988 on the United Democratic Front (UDF) and sixteen other progressive organizations have further accentuated the prominence of the African National Congress (ANC) as the leader of the struggle. It is ever more likely that a democratic South Africa would usher the ANC into power.

The strength of the National Party (NP) and the more certain position of the ANC as the heir-apparent lead the book in different directions. On the one hand, it would be useful to be able to begin to identify policies that, prior to majority rule, might form the substance of what Adam and Moodley (1986) term ‘real reform’. On the other hand, there is still considerable value in debating the urbanization policies that an ANC-led government might consider. Some resolution of this divergence is found in the fact that the issues surrounding urbanization will largely remain the same, regardless of whether South Africa is governed by the NP or led by the ANC. For example, there is already an intractable problem regarding the ability of the urban poor to afford housing and this will not simply disappear when the ANC comes to power.

Differences between the NP and the ANC are more predictable in the area of policy responses but, even here, one can argue that, when the NP considers ’genuine reform’ (Yudelman 1987), the differences between it and the ANC will narrow. I am alert to the fact that this position might appear surprising to many people and perhaps even insulting to supporters of the ANC. I hope the following will clarify what is being asserted.

The reason for being interested in establishing a measure of genuine reform is found in the likelihood that the NP will continue in power for some years to come, and also in the state’s ever increasing allocation of resources to the urban sector. Hitherto, progressive forces in South Africa scorned the government’s ‘authoritarian reform’ because the ‘reforms’ were not a product of negotiation. More recently, the evident strength of the state, in contrast to the apparent weakness of the opposition, has led many to re-evaluate this position and to conclude that, if the end to apartheid is still some way off, then genuine reform warrants less disdain. If this book helps one to distinguish between such reform and other policy shifts, then decisions regarding which policies to support and which to oppose should become all the more apparent.

An illustration of the value of having a measure of reform is found in housing policy: at the moment the government is urging the private sector to take primary responsibility for solving the housing crisis, whereas the Freedom Charter raises images of public housing. Neither response will address the needs of the poor. On the one hand, the housing needs of the poor do not constitute effective demand and the (formal) private sector will not help them. On the other hand, public housing is also of limited value since its cost has prevented countries, both capitalist and socialist, from building enough dwelling units. Public housing has a particularly dreary record internationally in that it has invariably been used to house bureaucrats and people having, say, incomes falling between the 30th and 50th percentiles.2 So the NP and the ANC may differ regarding the form of a desirable housing policy, but both should be disciplined by what has proven effective elsewhere. The consideration, not only of what is desirable, but also of what has ‘worked’ considerably narrows down the options – one finds that seemingly opposed positions are selecting policies from much the same menu.

While there is a tendency to reject government policy simply because of its apartheid origins, the above conclusion causes one to dissect that policy more closely. One should accept that, although most aspects to the government’s reform agenda deserve rejection, some may be worth supporting. The important point is that one should be able to make these distinctions and that one should make them with a view to a democratic future.

To sum up, this book is intended to be used both as a target and as a weather-vane. If it prompts discussion regarding the post-apartheid future, the reason for writing it will in large part have been realized. If, in addition, the policies can be taken as a measure of the distributional decency of the government’s urbanization policy, then the reader will be able to distinguish more clearly between the rhetoric and the substance of reform.

A focus on poverty

Most people think of reform in South Africa in terms of a movement towards democracy, but this is not entirely true for urbanization policy. The reason for this is that if ‘you abolished apartheid most South Africans would remain poor and lead lives of material deprivation’ (Freund 1986a: 124). The desirability of alternative policies is therefore primarily reflected in the extent to which they serve the material needs of the poor, and it is in this regard that I have asked, ’Which policy best contributes to the alleviation of poverty?’ The assumption underlying this focus is that policies that relieve poverty arise only as a result of pressure from the poor. I am attempting to draw forth effective options with the hope that this will enrich the political process when policies are debated.

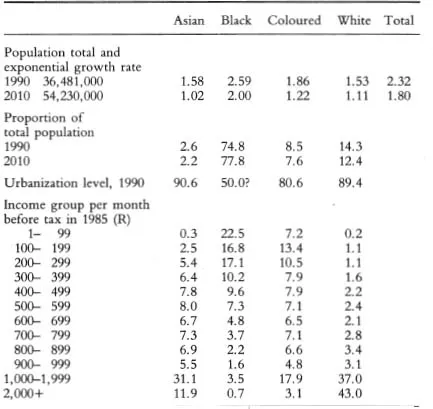

It is a bit disconcerting that a focus on poverty leads to an examination of the urbanization issues that affect blacks. Ordinarily, I would want to go along with the use, among progressive organizations, of the term ‘black’ to include ‘coloureds’3 and Asians, but it will become apparent that the material circumstances of the different groups differ so markedly that the narrower use of the term is more accurate when discussing urbanization policy. This contradicts the aracial future that one hopes for in a post-apartheid society and consequently requires further explanation. It is clear from Table 1.1 that future urban growth will preponderantly comprise the urbanization of a low-income black population – they are the poorest group in the country, constitute about 75 per cent of the population, have the highest population growth rate and an urbanization level that is well below that of the other groups. A number of specific problems follow: perhaps more than half the black population cannot afford cheap houses, which are priced around R20,000 (including land); areas zoned for whites, coloureds and Asians have a housing shortage of about 55,000 units, whereas in ‘black’ areas in the PWV alone there is thought to be a housing shortage of 350,000 units; it is blacks who suffer most from the inequitable access to land; and so on. Accordingly, it is not out of choice or any desire to speak in racial terms, but because blacks are the most poverty-stricken group, constitute such a large majority and are little urbanized that this book has mainly to do with the urbanization of the black population.

Table 1.1 South Africa: population size, growth rate, urbanization level, racial proportions and income distribution

Sources: Calculated from Johnson and Campbell (1982), Simkins (1983) and De Vos (1987).

Yet, while the above simplifies the problems that arise when aggregating South Africa’s racially differentiated data, it does not allow easy generalizations regarding the nature of poverty. Poverty is an elusive concept and I would be foolish should I claim a prior understanding of the problems of the poor. There is even considerable debate as to what poverty means! I therefore conclude this chapter with a review of the concept and a description of both the current and likely extent of poverty in South Africa.

Current urbanization policy is largely motivated by the security needs of the state and a short description of the policy and the negative consequences for black welfare is contained in Chapter 2. In the words of one commentator on this text, the chapter looks ‘at the apartheid system as the troubled soil into which the new government must sink its foundations’,4 as it shows that the legacy of apartheid will long burden future governments and the economy. This burden is particularly apparent in the structure of the ‘apartheid city’,5 and an extended example demonstrates the relationship between urbanization policy and poverty, and points to the nature of the problems a democratic government would encounter.

A bastardized city structure has arisen under apartheid. Pretoria is an extreme case, but Johannesburg also has a discontinuous urban structure, with pockets of isolated black residential development located at great distances from urban centres. This city structure is in direct contrast to the needs both of the poor and of an efficiently functioning city. Deprived communities in a city are dependent on ‘access to the economic opportunities and the social and commercial services which can be generated through the agglomeration of large numbers of people’ (Dewar 1986: 1). Access to employment and markets for the informal sector would be enhanced if urban activities were spatially integrated and occurred at high densities.

Such conditions would also make an effective public transport system possible. In contrast, the black townships, including those currently being created, reflect quite the opposite characteristics and they represent the isolation of the poor from the relatively wealthy. The consequence is a paucity of social and commercial services and an expensive transportation system.

This urban structure has been a deliberate artefact of apartheid policy, whose primary purpose has been the attempt to keep blacks at a ‘safe’ distance from the centres of production and the white residential suburbs, except, of course, for labour purposes. South Africa’s riot-torn cities are remarkable for the fact that most whites live and work ‘inside the laager’ which means that they seldom feel endangered, let alone materially affected, by the struggle – the riots occur largely in the townships. In effect, the access of the poor to employment and services, as well as the quality of their environment, are deliberately sacrificed in the interests of an illegitimate government’s attempt to maintain social control. A democratic South Africa would obviously attempt to redress this situation of urban isolation.

Policy options?

It is not too much of a caricature to claim that much progressive analysis of the post-apartheid future criticizes the current system at length, briefly considers the Freedom Charter, and concludes that ‘the people will decide’. As Gumede, co-president of the UDF, suggests below, it is surely possible to render a greater service:

Paul Bell: It seems that in any discussion of a new society by the progressive movements, more time is devoted to a critique of the present system than to the presentation of alternatives…

Archie Gumede: I agree. This is a situation which I cannot say is avoidable in our particular circumstances. We are on the run, and trying to be creative at the same time. I honestly become very worried, though, that sooner or later we are going to find ourselves in a real jam, because people do not have sufficient time to think, to discuss the various issues and possibilities.

(Leadership, 1987, 6: 54)

All this is not to argue that policy can be satisfactorily considered independently of its context, and a hypothesized political – economic context is discussed at length in the third chapter. On the assumption that the topic holds intrinsic interest for the reader, more attention is accorded to the competing images of the post-apartheid state than one would normally expect in a book on urbanization policy.

To start with, there are those who support a federal state and capitalism. This position is represented, in one form or another, by the ‘left’ wing of the NP, the opposition Democratic Party (DP), whose views largely represent an extension of the former Progressive Federal Party (PFP), and major business interests. Various homeland leaders, most respectably the late Phatudi and Buthelezi, also support federalism, but their opinions are likely to prove of little account.6 Next, there are those who support a unitary7 state and economic arrangements that range from a mixed economy to socialism. It is the formidable alliance represented by the ANC, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu), the UDF and the more recently formed Mass Democratic Movement (MDM) which is examined here. (The MDM comprises a loose alliance between Cosatu and the UDF, and other organizations, has no constitution and office bearers, and is a broad-based movement whose structure is intended to enable it to evade repression.) While there appears to be unanimity on the goal of a unitary state, it is in the nature of the ANC as an opposition alliance that there is considerable debate within the organization and its allies regarding the desired economic arrangements. This debate is examined through reference to the Freedom Charter,8 the ANC’s recent constitutional ‘update’ of the Charter, views within Cosatu, and the ANC’s relationship with the South African Communist party (SACP).

The discussion of the federal and capitalist image and the unitary and mixed economy image sets up two poles from within which a negotiated post-apartheid state is likely to issue. An important premise underlying this book is that the post-apartheid state will in fact be a product of negotiations. From the point of view of predicting the nature of the future South Africa, much would appear to depend on the manner in which the next government comes to power: if it occurs as a result of negotiation among relative equals, some compromise among the above options...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of tables

- List of maps

- List of figures

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Urban ‘reform’ under apartheid

- 3 Government and economy in a democratic South Africa

- 4 Land for housing the poor on the PWV

- 5 Regional economic policy

- 6 Urban and rural development in the periphery

- 7 Conclusion

- Appendix: The freedom charter and the ANC’s Constitutional Guidelines

- Bibliography

- Index