![]()

1 A multi-disciplinary analysis of the risks and opportunities of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam for wider cooperation in the Nile

Zeray Yihdego, Alistair Rieu-Clarke and Ana Elisa Cascão

Introduction

The Nile River is the longest river in the world, travelling for 6,695 kilometres from its source in the Great Lakes region until its discharge into the Mediterranean Sea in Egypt. The river passes through eleven riparian countries: Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, South Sudan, Sudan and Egypt. The main sources or sub-basins of the Nile are the Blue Nile, the White Nile and Tekezze/Atbara. While the White Nile is the longest sub-basin of the Nile, it only makes an estimated 15 per cent steady water contribution to the Nile; in contrast, the Blue Nile which originates in Ethiopia makes ‘up to 90% of annual Nile flows’ (NBI 2012: 26). However, this annual flow figure masks the significant variability in seasonal flows.

Hundreds of millions of people live in the Nile Basin. With respect to the former, the Nile Basin Initiative Atlas (NBI 2016) highlights that:

The current total population of Nile Basin countries is estimated at 487.3 million. Ethiopia has the highest population (99.4 million) closely followed by Egypt (91.5 million) and DR Congo (72.1 million). Eritrea (5.2 million), Burundi (11.2 million) and Rwanda (11.7 million) have the smallest populations.

(NBI 2016: 53)

The Atlas further provides that:

the combined population living within the Nile Basin (covering an area of 3,176,541 km2) is estimated at 257 million (or 53% of the total population of Nile Basin countries). Egypt has the highest population living within the Nile Basin (85.8 million), followed by Uganda (33.6 million), Ethiopia (37.6 million) and Sudan (31.4 million). Eritrea (2.2 million) and DR Congo (2.9 million) have the smallest populations within the Nile Basin.

(NBI 2016: 15)

The total population of Nile Basin countries will drastically increase in the next three or so decades. It is reported that,

by the year 2050, annual increases (in African population) will exceed 42 million people per year and total population will have doubled to 2.4 billion. This comes to 3.5 million more people per month, or 80 additional people per minute.

(Bish 2016)

Population dynamics are therefore set to have a real impact on the water resources management, development and allocation among Nile riparian countries.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) is a large-scale hydropower dam project, which has been under construction on the Blue Nile since 2011 – although the construction contract between the contractor, Salini Impregilo, and the Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation, was signed by the Ethiopian government in December 2010. The GERD is located in the Ethiopian portion of the Blue Nile Basin, close to the Sudanese border. With a dam height of 155 metres, 1,800 metres long, with a storage capacity of 74 CBM and with an upgraded installed capacity of 6,450 MW in electricity, the GERD will, on completion, be the largest dam on the African continent (Feyissa 2017). Ethiopia has recently announced that more than 57 per cent of the construction of this US$4.7 billion dam project has been completed (Feyissa 2017).

With an expected completion date of 2017, it is relevant and timely to explore the GERD’s regional significance to the Nile Basin generally and more specifically to the Eastern Nile sub-basins. The need for the Eastern Nile riparians (Ethiopia, Egypt, Sudan and South Sudan) to reconcile their current and future interests with respect to Nile water resources in an equitable and sustainable manner is evident, yet challenging, especially given their growing populations.

A further challenge is that the countries of the Nile Basin are both underdeveloped and diverse in terms of their socio-economic conditions (NBI 2012). The 2016 UNDP Human Development Report, for instance, classifies the majority of Nile Basin countries in the category of ‘low human development’, while Egypt and Kenya are classified in the ‘medium human development’ group. The importance of geography to socio-economic conditions is highlighted in the Nile Basin Report (2012), which suggests that,

[Egypt] has the advantage that most of its population live in the narrow tract of land along the Nile and in the Nile Delta areas, and its economy benefits from oil revenues. The headwater countries, in particular Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia, have been constrained in their efforts to provide similar quality of life for upstream riparian communities by the scattered settlement patterns and difficult terrain in the headwater areas.

(Nile Basin Report 2012: 108)

Alleviating poverty within these countries requires improved food and energy security for all. Rural populations in both Ethiopia and Sudan have extremely low levels of access to renewable energy (2 per cent and 7 per cent, respectively). Yet hydropower potential in the basin is high, particularly in the Ethiopian highlands where the hydropower potential is estimated at 45,000 mw (Salman, Chapter 2; GTP II 2015). At the same time, there is also significant potential to increase intra-basin power trade, between Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan and beyond the Eastern Nile sub-basin (Tan et al. 2017). However, any development is heavily contingent upon the equitable and inclusive sustainable development of the waters of the Nile River Basin. Moreover, food and energy security are intricately linked. Any development in irrigation to help address the pervasive undernourishment will have to be reconciled with potentially competing interests such as hydropower. While reconciling these potentially competing interests poses significant challenges within sovereign borders, Nile Basin states must also account for the needs and interests of other riparian states.

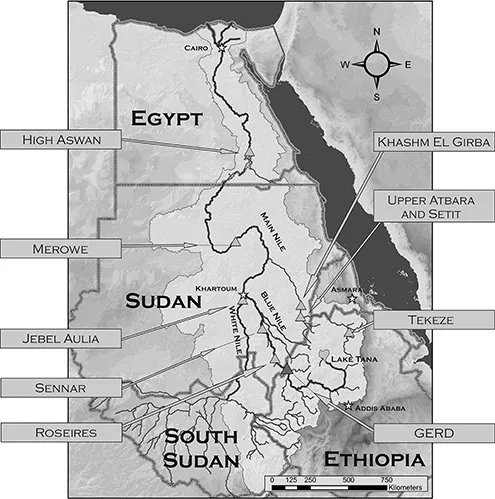

Figure 1.1 Map of Eastern Nile region, with reservoir locations.

Source: Wheeler et al. 2016: 613.

Addressing the multiple socio-economic challenges faced by Nile Basin states demands a regional approach. An intergovernmental platform, the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), was established in 1999 as a transitional arrangement gathering together all the Nile Basin riparians. Since its establishment, the NBI has been working towards promoting and advancing regional approaches to the social, economic and environmental challenges faced by the basin. However, population growth, the urgent need for sustainable development and the slow pace of cooperative efforts are placing more and more pressure on governments to move ahead with projects, even if they are mainly national in nature. As originally conceived, the GERD is one such example – although it is certainly not the first project of its kind in the Nile Basin. An assessment of both the Blue and White Nile Basins demonstrates that, for example, Egypt, Sudan and Uganda have all unilaterally developed large-scale infrastructure projects, particularly over the last two decades (Salman, Chapter 3). The GERD, however, is arguably the most significant given its size, location, its influence on transboundary relations between three key Eastern Nile Basin riparians, and its potential effect on regional hydropolitical relations at the Nile Basin level.

The GERD offers both risks and opportunities. As an opportunity, the GERD has the potential to foster cooperation by offering regional socio-economic benefits through the coordination and management of hydraulic infrastructures within the basin. Such benefits, it is hoped, will eventually contribute to an improved and a more efficient water management regime. An improved and more efficient water management regime may in turn assist in addressing the uncertainties that climate change is expected to bring to the basin – although it is not yet certain if this will mean more or less availability of resources (Siam and Eltahir 2017; Conway 2017). Coordination over the operation of the GERD and the other existing infrastructures may also prove to be a catalyst for additional benefits ‘beyond water’, such as a greater integration of markets and trade (Sadoff and Grey 2002), including in the energy sector. However, one of the most notable challenges in realizing these benefits is to ascertain and gain a broader agreement on the most appropriate legal, political and institutional arrangements that should be put in place among the concerned states.

Reaching that agreement has proven to be a significant challenge. In particular, because downstream and upstream riparians have historically displayed major differences in their perceived entitlements to the Nile waters. While downstream Egypt and Sudan have relied upon what they consider to be their ‘historic rights’, upstream riparian countries reject such claims and considered it to be contrary to the principle of equitable and reasonable utilisation and participation (Salman, Chapter 3).

It is not surprising then that, at least up until March 2015, the GERD was seen, particularly through the eyes of the media, as a source of political tension between Ethiopia and Egypt (Tawfik and Dombrowsky, Chapter 6). Egypt considered it as a violation of the 1902 Anglo-Ethiopian Nile Treaty, the 1993 Framework Cooperation instrument signed between Egypt and Ethiopia, and established principles of international water law – namely, the duty to take all appropriate measures to prevent significant harm and the obligation to protect the ecosystems of an international watercourse, in particular (Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2014). Ethiopia for its part maintained its long-standing position on the invalid nature of old Nile agreements, including the 1929 and 1959 Nile Water Agreements, and based its actions in furtherance of the GERD project on its right to make use of Nile waters. In maintaining its right to use the Nile waters, Ethiopia placed considerable emphasis on the fact that it contributes the largest share to the total Nile flows. Ethiopia further argued that the GERD would bring shared socio-economic and environmental benefits for all the three riparian countries, rather than causing harm to the two downstream countries (Horn Affairs 2014).

The environmental and economic implications of the dam in all its aspects (e.g. hydropower, agriculture, etc.) on Sudan and Egypt is open for debate. Egypt, in particular, has concerns over the short-term and long-term impacts of the dam on Egypt’s power generation capacity, irrigation potential and its economy in general. Ethiopia, for its part, insists that the hydropower project will bring economic, environmental and regional benefits even beyond the three Eastern Nile countries. Understanding the interests and concerns of the three countries with respect to the filling and operation of the GERD entails both challenges and opportunities, as discussed at length by Boehlert, Strzepek and Robinson (Chapter 7), Kahsay, Kuik, Brouwer and Van der Zaag (Chapter 8), Zhang, Erkyihun and Block (Chapter 9) and Wheeler (Chapter 10) in this book.

Despite the inevitable rounds of negotiations, the riparian states, assisted by expert studies, including an International Panel of Experts, have managed to navigate a cooperative path that seeks to reconcile their different interests (IPoE 2013; DoPs 2015; The Khartoum Document, December 2015, as referenced by Salman [Chapter 3]). The willingness of the riparian states to cooperate is reflected in the Declaration of Principles (DoPs) of March 2015, which endorsed established principles of international water law, cooperative mechanisms, and set out an agreement on how and which benefits of the dam will be shared and any negative impacts prevented. Although rather in a slow pace, the three Eastern Nile Basin countries are also undertaking additional environmental and economic impact studies on the GERD, as recommended by the IPoE 2013, through two French consultancy firms, BRLi Group and Artelia. It ought to be stressed that Sudan played a pivotal role in the trilateral negotiations on the GERD from the very beginning, and provided official backing to the project while constantly highlighting the downstream benefits of the GERD (see Cascão and Nicol, Chapter 5; Salman, Chapter 3).

Two observations recap the broader context of the GERD within the Nile Basin. First, although the attention of scholars is often focused on the views of, and relations between, Egypt and Ethiopia, the project is of great importance to the whole Nile Basin region including the multilateral cooperation processes within (Cascão and Nicol, Chapter 5). Second, while notable successes with respect to the multilateral cooperation processes have been achieved (see also technical cooperation under the NBI and political negotiations under the Cooperative Framework Agreement [CFA]) (Salman, Chapter 2), reaching a permanent legal and institutional framework that is accepted by all co-riparians remains a key challenge (Cascão and Nicol, Chapter 5).

Chapter overview of the volume

The contributions in this volume explore – from a range of disciplinary lenses – challenges and opportunities associated with GERD. One such perspective is law, which is considered from different angles in the first three chapters of the volume.

Following the current introductory chapter, Salman’s Chapter 2 considers the ways in which the ‘Gordian Knot’ associated with the CFA can be disentangled. The chapter therefore provides an important link between basin wide cooperative efforts and the specific context of the GERD. After providing a geographical, political and historical background to the broader question of sharing Nile waters, Salman outlines the controversies relating to colonial and post-colonial Nile treaties and agreements. This then leads to an in-depth exploration of the attempts made to foster basin-wide cooperation through, in particular, the CFA. Salman highlights that, although the main objective of the NBI since 1999 was the conclusion of ‘a cooperative framework agreement’, the major disagreement over historic or acquired versus equitable rights continued to be divisive in negotiations up until the adoption of the CFA. The CFA, Salman notes, was, while not without its controversies, an important step change in the evolution of international water law within the Nile Basin. Taking into account new realities and mediation efforts, including the DoP, Salman goes on to maintain that the events related to the GERD have the potential to disentangle the Gordian Knot of the CFA.

In Chapter 3, Salman explores the contents of the DoPs on the GERD and the processes thereof, and asks whether or not this development levels the Nile Basin’s playing field. In so doing, the chapter builds upon Salman’s previous chapter. As a background, Salman begins by looking at the relevant legal instruments and the history of dams in the Nile Basin. He provides a detailed account of the sequence of negotiations that led to the DoPs and the December 2015 Khartoum Document, which endorsed the decision to have French firms BRLi and Artelia conduct an impact study on the GERD. Lamenting the prevalence of unilateral dam development in the Nile Basin and highlighting the absence of water security of the two downstream countries in the Declaration, Salman argues that the DoPs and the December Document have brought ‘a new legal order’ that has replaced the 1902 and 1959 Nile treaties – one that is founded upon contemporary principles of international law. He further argues that through the endorsement of the fundamental principles of international law, ‘the playing field of the Nile Basin have been levelled’. Such levelling of the playing field should, he maintains, be ...