![]()

1 Introduction

During recent years, the front pages of the newspapers have recurrently denounced the lack of independence of the judiciaries by revealing corruption cases as well as political manipulation of the justices. In November 2004, President Lucio Gutierrez from Ecuador with support from the congress removed 27 justices (out of 31) from the Supreme Court and seven judges (out of nine) from the Constitutional Tribunal as the result of explicit accusations that the justices and judges were politically loyal to the former president. In April 2005, the judiciary was, once again, the target of political manipulation when Gutierrez purged both the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Tribunal as a way to mitigate the critics and the opposition to his government. The country remained for seven months without a Supreme Court and for ten months without a Constitutional Tribunal. In July 2007 the Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa carried out a controversial restructuring of the judiciary, in which the Supreme Court changed not only its name (to the National Court of Justice) but also the total number of justices (reduced from 31 to 21). That same year, the Constitutional Tribunal was once again purged, in this case as a result of political confrontations with the executive. In Argentina in 1990, President Carlos Menem increased the number of sitting justices of the Supreme Court from five to nine and appointed six new justices to the bench, since two of the sitting justices had stepped off because of excessive political manipulation. In 2003, the Argentine President Néstor Kirchner induced the departure of six justices: two of them were impeached, and the other four were forced to leave via threats of impeachment and moral coercion.

The Latin American courts are not an exception; other judiciaries around the world also suffer political manipulation by the executive. For example in Pakistan, in 2007, President Pervez Musharraf requested the resignation of Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry due to their political confrontation. The Chief Justice was physically restrained for several hours from leaving the president’s office until he presented his resignation. In Zimbabwe, in February 2001, President Robert Mugabe threatened to remove the justices of the Supreme Court by force unless they resigned from the bench or reversed their rulings on recent land cases. A couple of days later, Mugabe forced Chief Justice Anthony Gubbay to resign from the bench, arguing that his government could not guarantee Gubbay’s safety if he remained in office. Soon after Gubbay left the office, two other high court justices (Ahmed Ebrahim and Nicholas McNally) were also asked to resign.1 As a way to ensure that the Supreme Court’s decisions would be favorable to Mugabe’s regime, in July 2001 the president packed the court by increasing from five to eight the number of sitting justices. Not surprisingly, the new court overturned the ruling of the old court on the land cases, as the government had expected.

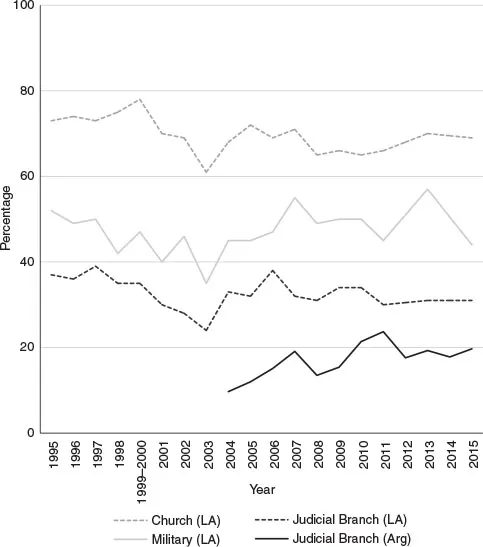

Political manipulation of the judiciary is a deep-rooted problem for underdeveloped countries. The increased number of scandals and corruption cases within the judiciary has contributed to a great deterioration in the citizens’ confidence in the institution. According to the Latinobarómetro surveys (2015), from 1996 to 2015, on average, only 33 percent of Latin American citizens had confidence in the judiciary, less than half of the level of confidence that citizens had in the church (70 percent) and on the military (48 percent). Survey data from Argentina reveals a more dramatic situation regarding the level of trust in the national judiciary, on average, between 2004 and 2015, 17 percent of national citizens had confidence in the judiciary (Observatorio de la deuda social Argentina 2017). Figure 1.1 shows that since 2015 Argentinians had increased their level of trust in the judiciary but the overall performance is still low.

Evidently, the scandals related to the administration of justice, and the excessive political manipulation of judges has undermined the citizens’ level of confidence. Montesquieu (1752) and Alexander Hamilton (Madison, Hamilton, & Jay 1787–1788) would argue that the numerous attacks on the judiciary happened because the judiciary is the weakest of the three branches of government. Even though in most countries justices are appointed for life (or long-term tenures), the fact that the congress and the president are often in charge of both the appointing and removal processes makes justices, in underdeveloped countries, often vulnerable to those authorities. Studying the dynamic of vacancy creation in the Supreme Court can reveal valuable information about inter-branch relations, since judicial nominations offer a key political means for executives to enhance their control over the judiciary. Under normal circumstances, vacancies should be isolated events resulting from retirement, death or the end of the term (in those cases where justices do not have life tenure). However, if vacancies appear frequently, then this pattern may be indicating that there are other factors affecting the stability of a justice in office. In industrialized democracies like the US, vacancies in the Supreme Court are isolated events, since justices serve an average of 12.5 years (Zorn & Van Winkle 2000); in contrast, in underdeveloped countries such as Bolivia (with a ten-year tenure), vacancies are much more common, because the average tenure is less than four years (Castagnola & Liñán 2011). In Argentina, between 1900 and 2014, justices have stayed in office on average less than seven years; furthermore, every 1.2 years there has been a vacancy in the court. At the subnational level in Argentina there is also great variation in the stability of the justices: between 1983 and 2009, justices from Corrientes with life tenure remained in office an average of 2.5 years, while justices from Buenos Aires, also with life tenure, have served, on average, 8.41 years. These significant variations in the level of judicial turnover reveal that in some cases justices do not voluntarily leave the bench; rather, there must be other factors influencing their departure. Why do justices remain in office for such a short time despite having life tenure or long-term tenure? What factors account for variations in judicial turnover across cases? The objective of this research is to provide an answer to these questions by systematically examining what factors have influenced justices’ stability in office over time in both the Argentine National and the Provincial Supreme Courts. By studying the timing of judicial turnover it is possible to identify whether justices voluntarily step off the bench or leave as the result of political manipulation by the incoming executive. This close examination of the instability of Argentine justices aims to shed light on debates about judicial independence in developing democracies.

Figure 1.1 Public Trust (%).

Sources: Observatorio de la deuda social Argentina (2017) and Latinobarómetro (2015).

More generally, the puzzle of justices’ instability in office challenges several assumptions about executive-court relations and judicial behavior. First, the American political literature offers a model of judicial turnover based on the assumption that the justice’s own decision to step off the bench is influenced by whether or not the justice shares the same political preferences as the president and the Senate (Hagle 1993; Spriggs & Wahlbeck 1995; Zorn & Van Winkle 2000). The rationale of the strategic retirement strategy is based on the idea that justices are willing to give their seats to another like-minded justice but not to a justice with opposite political preferences. The underlying assumption of this argument is that the longevity of justices in office is mainly determined by the justices’ own decision. Even though this assumption holds perfectly for the American case, for underdeveloped countries it is problematic, because there the longevity of justices in office appears to be determined by the executive rather than by the justices themselves. As the earlier examples illustrated, in those countries vacancies in the high court are basically triggered by presidents either inducing the departure of justices through undemocratic decisions, or threatening them with impeachment or moral coercion. Historical data on justices of the US and Argentine Supreme Courts reveals that in Argentina justices have not voluntarily stepped off the bench. Between 1900 and 2007 in the US Supreme Court, 54 justices departed from the bench mainly due to death (46 percent) and voluntary retirement (44 percent), whereas a small number (10 percent) resigned for other reasons (Ward 2003). In Argentina, in comparison, during that same period 832 justices departed from the bench for these reasons: 37 percent were removed as a consequence of a change in the political regime from military to democratic or vice versa; 31 percent resigned from office as a consequence of a change of government within the same political regime; 20 percent died while in office; 6 percent were impeached; and the remaining 6 percent retired voluntarily (Kunz 1989; Pellet Lastra 2001; Bercholc 2004; Tanzi 2005).3 Consequently, in Argentina voluntary departure (as the result of natural legal – that is, retirement – and biological – that is, death – conditions) was not the most common explanation for the high judicial turnover.

Second, there has been a large increase in the study of judicial independence in Latin America. Even though Argentina has the most studied Supreme Court in Latin America (Kapiszewski & Taylor 2008), the existing literature does not explicitly address the factors that influence a justice’s decision to leave office. Studies to date affirm that life tenure for Argentine justices is not respected, given that the way justices vote (regarding, say, the constitutionality of a proposed law) can account for their instability in office (Iaryczower, Spiller, & Tommasi 2002; Scribner 2004; Helmke 2005). More precisely, these studies focus on how political incentives and the political environment shape the justices’ decisions and assume that those decisions ultimately determine the justices’ stability in office; however, no systematic research empirically tests this assumption. Thus, if justices can regulate their stability on the bench by whether or not they rule against the ruler, then why don’t they simply do that? Why is there, in fact, a high judicial turnover in the country? In other words, the importance of the justices’ voting behavior as a mechanism of survival strategy on the bench is called into question.

The puzzle of justices’ instability in office also raises concern about executive-court relations. Along with the previous hypothesis, another relevant untested assumption in the literature is that only those presidents with strong political power (i.e., unified governments with supermajorities in the legislature) can craft a supportive court and affect justices’ stability in office (Iaryczower et al. 2002; Bill Chávez 2004). This assumption is related to the previous one, since it implies that only those presidents who have the political power to formally remove a justice from office (i.e., by impeachment) will obtain a supportive court. These studies are severely limited because they examine only whether or not the president has the political power to remove a justice from office, but not if it is only those strong presidents who actually do so. Even though this assumption seems convincing, governments rarely have had supermajorities in the legislature sufficient to impeach a justice. If that is the case, how can the high instability of justices be explained? Were those justices removed from office only by those presidents who had the political power formally to do so?

As a way to fill the gap between the American and the Latin American theories, this study begins with the alternative hypothesis that in developing democracies, the greater the political proximity between the ruling executive and the justice, the lower the probability that the justice will leave office. In contrast, in industrialized democracies, judicial turnover is independent of ideological changes in the executive. This is because executives, while in power, want to have a supportive court as a way to maximize their political influence on the decisions of the judiciary. The executive can craft a supportive court not only by appointing friendly justices, as the American literature has long recognized, but more interestingly by influencing when a vacancy will occur either by removing unfriendly justices or by packing the court with loyal justices.

Design and Methodology

Argentina, in terms of both the National Supreme Court and the Provincial Supreme Courts, represents a textbook case for the study of factors affecting the instability of justices in office. Argentina is a federal country with separate judicial entities at the provincial level; moreover, each province is autonomous vis-à-vis the national government in the design of its own institutions, producing a high degree of internal heterogeneity in the constitutional design. Precisely because of the persistent institutional instability, where from 1930 to 1983 democratic and military governments ruled interchangeably followed by a period when the administration changed as the result of party competition, Argentina can be considered a developing democracy. In the early ’80s, the country, as well as other countries in the world, entered what is known as the third wave of democratization and thus the democratic institutional consolidation process (Huntington 1991).

Previous studies have also shown that Argentina is the theory-generating case for studying executive-court relations in developing democracies. Argentina was used in studies as the classical example of a third wave democracy born with a weak judiciary (Bill Chávez 2004). The constant political manipulation by the executive, and the incapacity of the judiciary to limit attacks on itself, illustrate the difficult situation also present in other developing democracies. Another group of scholars (Iaryczower et al. 2002; Scribner 2004; Helmke 2005) chose Argentina as a case study to demonstrate that, even with the presence of a weak judiciary, Argentine justices have challenged executives by strategically ruling against them; what they reveal, however, is simply that executives do not have total control over the justices’ decisions.4 However, these studies have clearly overlooked the high degree of internal heterogeneity in the country, since most of the research was carried out at the national level (i.e., on the National Supreme Court). Even though Bill Chavez (2004) incorporates into her research two Argentine provinces (Mendoza and San Luis), the research illustrates only that there is an internal heterogeneity at the subnational level; it does not examine the causal connections in the other provinces that have undergone other experiences. As a way to overcome this deficit, this research employs the subnational comparative method (including all 23 Provincial Supreme Courts)5 to analyze within-country variations (Snyder 2001). It is precisely these variations at the subnational level that would not only shed light on the factors that account for those differences but also would allow development of a mid-range theory about the stability of justices in office that should be applicable to other developing democracies.

More generally, studying the provincial judiciaries in Argentina is of substantive relevance. First, the provincial judiciaries play a central role in local politics, since governors envision this institution as another key political resource to enhance their power. Studying the judiciary over time and across provinces can contribute to understanding how the configuration of local power, as well as diverse institutional design, affects the stability of the justices in office. By doing so, this research redirects attention to the neglected role of the separation of powers at the subnational level, the most overlooked aspect of the literature on fed...