Four-beat verse and children’s poetry

The opening stanzas of “Careless Matilda” by the early nineteenth-century writer for children Adelaide O’Keeffe, strike a characteristic moralising note:

“Again, Matilda, is your work undone?

Your scissors where are they? your thimble gone?

Your needles, pins and thread and tapes all lost;

Your housewife here, and there your work-bag tossed.

Fie, fie, my child! indeed this will not do,

Your hair uncombed, your frock in tatters too;

I’m now resolv’d no more delays to grant,

To learn of her I’ll send you to your aunt.”

(99)1

The sermonising tone may not be altogether unusual for children’s verse at this period (the reprobate Matilda of course learns in due course to appreciate the delights of orderliness), but what is unusual about “Careless Matilda” is its metre. Although iambic pentameter was the dominant metre in English poetry written with serious intent from the eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries, it has always remained a rare visitor to the land of children’s poetry. Its association with Shakespearean drama and Miltonic epic has no doubt counted against its use for lighter verse, as has its closeness to speech rather than to song, and its consequent resistance to memorisation. (The sheer length of the line might be thought to have been a disadvantage too, though longer lines have been highly successful in children’s poetry when in an appropriate rhythm – the 16- to 18-syllable lines of Bret Harte’s “Miss Edith’s Modest Request,” for instance, have a rollicking triple movement that is far removed from the earnestness implied by the pentameter.)

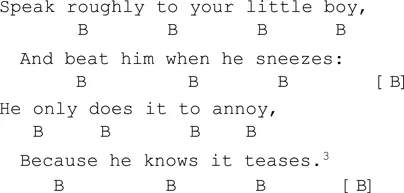

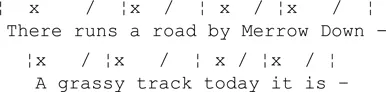

If the five-beat line is infrequent in children’s poetry, the four-beat line is everywhere.2 Or, to be more accurate, the four-beat rhythm in its various manifestations is everywhere, since one of the major differences between the two rhythms (which between them account for virtually all regular metres in English) is that while the five-beat sequence – almost always taking the form of the iambic pentameter, rhymed or unrhymed – doesn’t lend itself to easy division or multiplication, the four-beat sequence slides easily into smaller or larger units. So strong is our yen for groups of four beats that we easily supply a missing one when a line has only three. And these clusters of three and four beats are the constituents of many different arrangements of line-lengths. The classic ballad metre of 4.3.4.3 beats, much used in hymnody, where it is known as “common measure,” appears frequently in children’s verse as well. Here is the first stanza of Lewis Carroll’s “Lullaby,” with a simple form of scansion showing the beats below the line, with [B] indicating a beat that is felt, not spoken:

Characteristic of this stanza form are the feminine endings of the shorter lines, going some way towards fulfilling the need of a fourth beat, and the a b a b rhyme scheme. In contrast to O’Keeffe’s staid pentameters, where the weaker rhythmic form allows the severe tones of the grim speaking voice to emerge, the strength of this four-square metre encourages something much closer to a lively chant that turns the repellent subject-matter into comic irony.

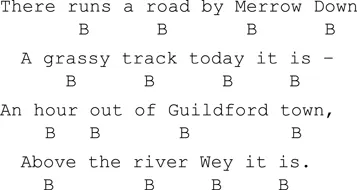

The full version of the 4.4.4.4 stanza (“long measure” in hymnody) is also common in children’s verse:

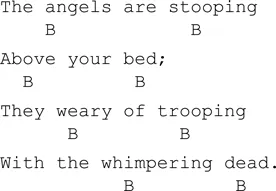

Sometimes the four-beat lines are divided in two, but the group of four can still be felt:

Less common is the combination into a single line of two four-beat groups; somewhat more frequent is the line of four and three (Blake’s “Holy Thursday” from Songs of Innocence is a well-known example of the latter).

In all these cases it will be evident that the line of four beats is part of a larger rhythmic structure experienced as a hierarchy of two, four, eight, and sixteen beats. In fact, it is somewhat misleading to speak in terms of lines, since the rhythmic divisions are determined not by the layout on the page but by the inherent structuring of the four-beat metre. It is largely rhyme that determines how the verse is laid out visually, and Yeats’s poem, for instance, would not sound very different if set as four-beat lines with internal rhyme.

The most common name for what I have been calling four-beat verse is “tetrameter,” a name derived from the habit of using Latin and Greek names for English metre, and, as in Latin and Greek, dividing the line into repeated feet. A tetrameter line, therefore, is a line of four feet. Carroll’s and Kipling’s stanzas quoted above are clear examples of a metrical form that can be analysed as four iambic feet:

and so on. But this is rather unusual in children’s verse, as it is in nursery rhymes and ballads. More common is a verse form that resists this kind of analysis. How would Yeats’s “Cradle Song” be divided into repeated feet? And what would be the point? Its clear, regular rhythm is not dependent on recurring blocks of stressed and unstressed syllables, but on the strong beats that arise naturally from a reading or recitation, and the groups into which they fall. Lines in this poem may begin with either one or two unstressed syllables and end on either a stressed or an unstressed syllable; and there may be either one or two unstressed syllables between the beats. This type of verse has gone by various names, the most convenient perhaps being the one borrowed from the Russian name for a similar metrical form, the dolnik. In what follows, I hope to show by means of a few examples both the ubiquity and the effectiveness of the dolnik, as the most immediately recognised and most memorable metrical form in English, across two hundred years of children’s poetry.

The uses of dolnik verse in children’s poetry

Partly because it does not conform to the rigid patterns of the most “literary” type of English versification – accentual-syllabic metre – and has therefore proved a challenge to critics, and partly because of its association with popular verse, the dolnik has seldom been appreciated as a major form capable of being exploited by skilful poets for many different types of poetry.4 And one of the reasons why the formal achievements of poetry written for children have not been widely acknowledged has been dolnik verse’s resistance to traditional modes of metrical analysis. (There also appears to be a degree of prejudice in pedagogic circles against any metrical, rhymed verse; Richard Flynn notes that many teachers prefer to use free verse and haiku, even though studies have shown that children themselves prefer verse with rhyme and metre [77].) A short essay can demonstrate only a few of the ways in which dolnik rhythms can contribute to the energy, vividness, and tonal complexity of children’s verse.

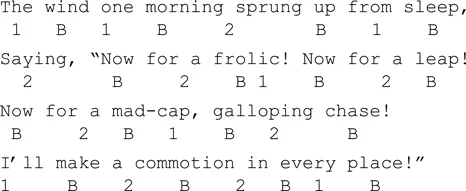

“The Wind in a Frolic” by William Howitt (1792–1879) is too long to quote in its entirety, but a consideration of some lines should be sufficient to show how valuable the dolnik is for certain descriptive purposes. I will indicate beats as before, and add a numeral to indicate the number of syllables between beats. The poem, written in four-beat couplets with all beats realised, begins as follows:

It will be immediately evident that this verse cannot be categorised as iambic or trochaic, anapaestic or dactylic, duple or triple. It begins with what seems to be an iambic line, with only one departure: the extra syllable in “morning sprung up,” at least as I read the line. (It would be possible to read “SPRUNG up” instead of “sprung UP,” in which case the extra syllable would come between “sprung” and “sleep”) We may call this two-syllable interval a double offbeat; the others are single offbeats. The higher the proportion of double offbeats, the more the verse slips into a ONE-two-three, triple movement.5 The relatively sedate rhythm of the opening immediately gives way to something jauntier in the second line, where now it is the triple rhythm that dominates from the very first word. In another type of verse, we might be tempted to give the first syllable of “Saying” a stress, but the insistence of the four-beat rhythm is such that we can instinctively demote it to a pair of quickly spoken unstressed syllables. The third line sustains the sprightly rhythm, this time beginning on a beat, and again contains only one single offbeat. Notice, however, that this offbeat – the second syllable of “madcap” – can be given a certain degree of stress and still sustain the vigorous rhythm. The fourth line then inverts the pattern of the third, with single offbeats at the ends and double offbeats in the middle (unless we choose to pronounce “every” as three syllables, which would keep up the triple rhythm to the end).

The description of the wind’s antics that occupies the major part of the poem (it is sixty-one lines long, thanks to one couplet being extended by an additional rhyming line) is largely in triple rhythm; that is to say, double offbeats predominate. The following are typical lines:

The turkeys they gobbled, the geese screamed aloud,

And the hens crept to roost in a terrified crowd;

There was rearing of ladders, and logs laying on

Where the thatch from the roof threatened soon to be gone.

Once this rhythm is fairly under way, we have little difficulty in suppressing the occasional syllable that would normally be stressed, as with “screamed” and “crept”: “the GEESE screamed aLOUD”; “the HENS crept to ROOST”. Dolnik verse, unlike its stricter cousins, thinks nothing of overriding natural speech patterns in favour of a strong, regular rhythm; skilful users of it ensure that the syntactic and lexical properties of the words in question are such that the suppression can happen without a sense of disruption or tension (except where this contributes to the effectiveness of the verse).

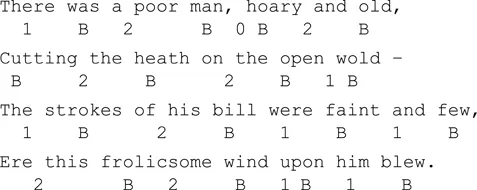

The wind upends a schoolboy, but the rhythm lets us know that we need not take this event too seriously. But then there is a change of mood, and metre:

These lines have more single offbeats than most of their predecessors, and one zero offbeat, the only one in the poem. This shift puts something of a brake on the helter-skelter rhythm, and encourages us to think of the old man not just as a figure of fun, as the schoolboy had been; the slower movement of the lines invites the reader to pause on the real predicament of an impoverished, elderly man subject to the force of the wind.

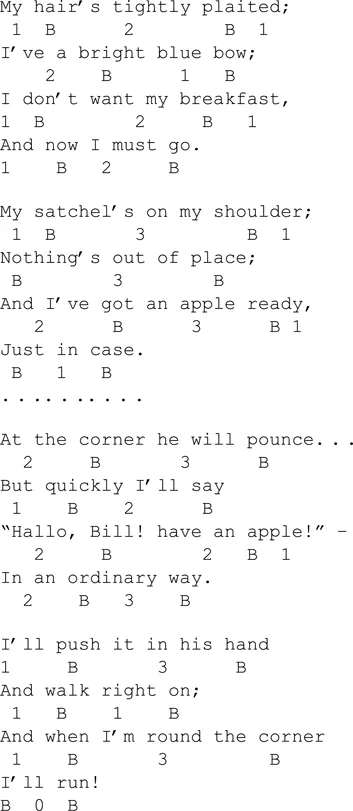

Although dolnik verse most naturally lends itself to lighter modes, this is not its only capability. For an illustration of a poem that explores the less light-hearted potential of the dolnik, and pushes at its formal boundaries, we may turn to a work by the twentieth-century poet John Walsh (1911–72), “I’ve Got an Apple Ready.” The poem’s ten stanzas, spoken by a young girl, relate her plan to defuse a potential clash with the frightening “Bill Craddock” who always waits for her on the way to school. The opening and closing pairs of stanzas are as follows:

This poem has none of the breezy bounce of most dolnik verse for children; this is a case where the chopped-up lines leach out some of the four-beat form’s jauntiness, although the metrical scheme remains intact. We can rewrite the opening stanzas with four-beat lines to gauge the difference made by the layout: now the rhythmic movement seems easier and more relaxed, since we can read on across the mid-line punctuation to sustain the four-beat movement, pausing only at the rhymes:

My hair’s tightly plaited; I’ve a bright blue bow;

I don’t want my breakfast, and now I must go.

My satchel’s on my shoulder; nothing’s out of place;

And I’ve got an apple ready, just in case.

There are other rhythmic features that inhibit a carefree mood and suit the anxiety of the situation, the most important being an alternative rhythmic form that haunts the lines. Several of the offbeats in the scanned stanzas have, unusually, three syllables, and three successive unstressed syllables in English verse often imply a beat on the middle one. Let us rewrite these lines further to increase the number of triple offbeats – which can now be heard as offbeat–secondary beat–offbeat:

My hair is tightly plaited;

I’ve a bright blue bow;

I don’t want any breakfast,

And I’ve really got to go.