![]()

Chapter 1

Understanding the ‘Small’ Society

Research problem: norms as ‘frameworks’ for action

Studying the penal world through the notion of norm appears natural in terms of sociological research. But sociologists and economists have long debated the nature of social action: is it rational or normative? In this way, the contradiction between the action that is guided by norms and the rational action could be described as follows:

'Rational action is concerned with outcomes... Action guided by social norms is not outcome-oriented... Even complex norms are simple to obey and follow, unlike the canons of rationality which often require us to make complex and uncertain calculations'

(Elster, 1988, p. 357).

Consequently, let us discuss the role of the norm in social organization.

Institutional approach

Our first landmark on the road toward a better understanding of the norm is marked by the institutional approach, which currently lies at the border between economics, sociology, history and law. Although it is not yet a new theory based on its own methodology, the institutional approach is of interest to us when it comes to researching a composite vision of norm.1 The strength and the weakness of this approach lie in its interdisciplinary character: it is the notion of institution that unites such very different disciplines.

'The institution [is] the set of norms and behaviors generally followed and spontaneously respected by the members of a group that acquire in this manner a character of stability independently of any explicitly stated legal obligation'

(Lochak, 1993, p. 305).

Viewed in this manner, the institution distances itself from the behavioral model imposed on individuals to become, rather, a device for coordination. Although institutions are not imposed by a discretionary power, individuals respect them.

The focus on voluntary submission serves to develop an image of a compromise between the various social sciences: individuals respect the prescriptions of the institutions since this enables them to fulfill their own interests better. In situations of interdependence, the ability to complete an individual project involves taking the project of others into consideration and, as a result, considering actions.

'Even though other people's goals may not be incorporated in one's own goals, the recognition of interdependence may suggest following certain rules of behavior, which are not necessarily of intrinsic value, but which are of great instrumental importance in the enhancement of the respective goals of the members of that group'

(Sen, 1987, p. 85).

In other words, the primary task of institutions involves facilitating the coordination of free agents whose actions are not subjected to an absolute determinant. Moreover, individuals have an interest in producing institutions in situations in which they are not provided a priori. Several experiments have demonstrated that individuals who are isolated from the influence of the usual institutions very quickly start building their own institutional space.

'This basic human need, which I choose to call law is related to what in other contexts is referred to as the product of socialization... People have a natural inclination to build laws governing their relationships'

(Weyrauch, 1971. p. 58).

Penal subculture

The understanding of the dual nature of norm will guide our study of a particular institutional space-the norms that structure common life in detention. Two types of norms organize life in detention. The first includes the official norms and regulations, imposed by the Law and implemented by the penal administration and the corps of guards. These norms provide a perfect reflection of the understanding of norms developed by classical sociology. Although we will devote a portion of our study to these norms, we will not focus on them. The second type includes the norms that are spontaneously developed and applied by the inmates so as to make their life in detention more bearable, socially. Just as each closed group makes its own laws for social life, the prisoners draft their own 'constitution'. 'The law of a tribe or extended family... is really a program for living together supported by the basic logic of the system as a whole' (Weyrauch, 1971, p. 51). The 'law' of the inmates is distinct in that it cannot be based on the logic of the system as a whole.

'Prison subculture comprises norms, customs, rituals, language and mannerisms which depart from those required by penal law and prison rules

(Platek. 1990. p. 459).

The following analysis will focus primarily on the second type of norms essentially since these norms are constructed as devices for mutual coordination and interpretation, which classic sociology does not take into consideration. 'Here, people are entitled to do everything they want, within certain limits. No one imposes their will, no one violates the right to private space, no one forces another to do something that other person does not want to do. What is important is not stepping outside the borders, respecting the rules... rules which have been developed over dozens of years.'3 From this perspective, the penal subculture may be viewed as the expression of the individuality of the inmates, the desire to create their own society, even under very harsh external constraints. As a result, the study of the penal subculture is part of the search for a response to a global challenge which sociology has been facing since its creation. The job of sociology is to 'give the right to speak to those who do not have it' (Touraine, 1993, p. 38).

After providing a functional definition of the subculture, we will proceed to sketch out its structure. The production of the subculture as a set of institutional frameworks for the everyday life of a small group is determined socially. The make-up of the group, its organization and its position with respect to the 'large' society characterize the subculture. 'Instead of using beliefs to explain the cohesion of the society, we have used the society to explain the beliefs' (Douglas, 1986, p. 40). In pursuing this line of research, we will attempt to trace the explanatory links between the special characteristics of the social organization of the penal world and the parameters of the penal subculture. For example, the social organization of the world of the guards does not allow them to develop a specific guard culture. As certain studies show, the guards develop cognitive markers individually and these markers vary from one guard to another (Chauvenet et al., 1994, pp. 192-193).4

When speaking of the penal subculture and its basic parameters, we will use a grid developed by Anthony Giddens. In particular, he makes a distinction between consciousness that is theoretical and practical (everything that individuals know tacitly, without knowing how to speak about it directly), extensive and intensive (frequently invoked during the course of everyday life), tacit and verbalized, formal and informal, weakly and strongly sanctioned (Giddens, 1984, p. 22). In this way, the penal subculture could be described as primarily practical, intensive, tacit and verbalized, informal and strongly sanctioned. As for its practical character, we encountered several problems when we asked our interviewees to theorize a little about their experience of life in detention. Although the rules of the penal subculture are carefully and clearly formulated, they still belong to the oral culture. The idea of drawing up a written 'code' of penal life has never been implemented,5 despite the existence of a sophisticated, virtually democratic procedure (voting for 'representatives' by an assembly) for implementing a new norm. These characteristics must be taken into account by means of the methodology chosen to research the penal subculture. We will detail this in greater depth later.

The search for a new societal model

The usual view of the penal world grants it a place 'outside' society. The alternative perspective proposed by Michel Foucault, in which the prison is merely a link in the chain of norm-setting authority, does not stand up to the criticism that stresses the complex character of the norm. We observe voluntary submission to the norm even in prison-the penal subculture is the invention of people who are deliberately subjected to a norm-setting authority that is virtually absolute. Simply mentioning the norm is not sufficient to account for the phenomenon of discipline in the prison and in the society that surrounds it. We need to question its social content, its sources and its social structure. If it is no longer the norm that makes the link between the 'small' penal society and the 'large' society, must we go back to the opposition between 'here' and 'there', which is so well-known as a result of anthropological research?6

Without claiming to be able to find a solution that can apply generally to other societies, we propose to make the following hypothesis in the post-Soviet context: the study of the 'small' penal society gives us an understanding of the way in which post-Soviet society is organized since it can be broken down into several 'small' societies (not necessarily penal in nature) and does not exist in a normative, unified and homogenous space, namely a 'large' society. In other words, post-Soviet society in general functions in a manner that is comparable to that specific to the 'small' penal society. The expression 'small' society, which we will refer to on several occasions during the course of our research, has several connotations that could hinder an accurate understanding of the opposition between the 'small' and 'large' societies. In fact, we use 'small' society to refer to a social organization that is not institutionalized, with no mediation between the State and the everyday lives of ordinary people, without any political representation of the interests of ordinary people. In short, it refers to an undemocratic society in which modernization has not been completed, which leads to the application of the modern analogue of the Latin term pittittus (young, not as old as the others).' In this way, when we speak of the 'small' society, we focus on the incomplete modernization, and the local, non-institutional and informal character of the social organization.8

Research hypotheses

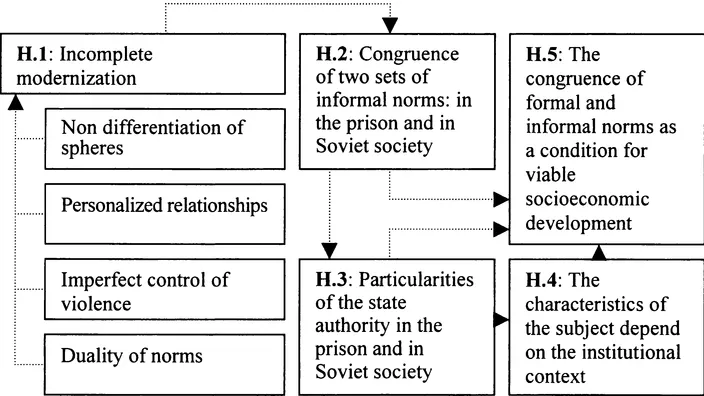

When opting to research daily institutional frameworks,9 we developed a series of hypotheses. While making no claim to produce a 'large schema', we can sketch them out as follows (Figure 1.1):

Figure 1.1 Research hypothesis

Incomplete modernization: the ideal type of ‘small’ society

Constructing an ideal type10 of society that is characterized by the lack of differentiation of spheres, the personalization of relations, the imperfect mastery of violence and the duality of norms, serves to qualify the situation in which Russian society is found as a result of incomplete modernization (H.l). In other words, the transformation of the 'small' society, which is both localized and personalized, into a 'large' society, has not been completed. This observation bears no value judgement; it merely reflects a particular structural and functional organization of society. As a result, we need to avoid using adjectives such as primitive or less civilized to describe it. As Alain Touraine correctly remarked with respect to Latin American societies, 'By what right can we consider the mixing of private and public life as more "primitive" than their separation?' (Touraine, 1988, p. 159). The other common differentiation, namely that between a non-industrialized society, an industrialized society and a post-industrialized society, does not seem pertinent to us within the context of our study since it focuses on the technical organization of the society. For example, it is possible to imagine an industrialized society that is not modern at the same time. In this way, we can define Poland's Solidarity, the first social movement in the Soviet-type societies, as 'the fight for modernization and economic growth in a society in the process of industrializing' (Touraine, 1992, p. 273). We prefer, as a result, to avoid shortcuts that have a value, judgment or technical connotation. For this reason, incomplete modernization seems justifiable. Non differentiation of spheres The structural definition of modernization implies the transformation of the simple society, without means for separating the various spheres of daily activity, in...