- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This title was first published in 2000: An exploration of the ways in which social welfare in two countries, half a world apart, may have similarities. Through identification of the differences and similarities of social welfare in Britain and Malaysia, the editors hope that we may be able to learn from one another as well as to contribute to debates both in our countries about how to respond to globalization and about global social policy. Accordingly, the contributors arranged themselves into pairs - one Malaysian, one British - to write reviews of one of each of the six areas of social welfare. Along with an opening chapter in which the aim was to identify a number of frameworks and issues that would allow the rest to be put into a context, the 12 chapters, each restricted to around 5000 words, provide a service-by-service account.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Social Welfare East and West by John Doling,Roziah Omar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Britain and Malaysia: the development of welfare policies

ANN DAVIS

JOHN DOLING

ZAINAL KLING

JOHN DOLING

ZAINAL KLING

Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to assist the understanding of developments in the individual elements - service sectors - of welfare policy, discussed in subsequent chapters. This is achieved, in part, by the presentation of brief, historical accounts of the broad characteristics and evolution of welfare policies in the two countries. These accounts are themselves devices that, through specific example, identify the location of Britain and Malaysia in wider frameworks encompassing all industrialised countries - both east and west. The first of these frameworks - the concept of welfare regimes starts from the assumption that industrialised countries can be classified according to the particular type of welfare model they have developed. As an approach, it is one that emphasises difference rather than similarity and emphasises the dynamics of the political, the ideological and the cultural in shaping difference. The second framework, in contrast, emphasises the process of globalisation in establishing conditions that are common across countries and may be thought of, though not necessarily so, as leading to some convergence, or greater similarity, of welfare systems.

Whereas these two frameworks constitute distinct approaches, they are not mutually exclusive in the sense that to pursue an interest in how countries might be similar, to have similar pressures on them and to act in similar ways, does not rule out the concurrent exploration of ways in which they are different and make different decisions. In other words, for the purposes of focusing on social welfare in Britain and Malaysia we can - and should - both compare and contrast, exploring ways in which their economic paths have been accompanied by similar forces and similar responses at the same time as noting and defining aspects that set them apart both from one another and from their regional settings.

Out of this approach a number of themes are identified: the nexus of family values and the role of women that can be seen to underlie different welfare approaches in the two countries; developments in labour markets, particularly associated with high levels of unemployment; and, developments in public expenditure constraints. One dimension of the themes, particularly relevant to our study, is that politicians in both countries are increasingly faced with the same challenge: in short, deciding what sort of welfare state is compatible with the objective of enhancing national economic competitiveness.

Welfare regimes

Methodologically consistent with the Weberian notion of ideal types, welfare regimes are caricatures of approaches to welfare, providing one-or two-sided templates against which actual welfare states can be compared and contrasted. They are not descriptions but abstractions; and they are not right or wrong but merely more or less useful for the purpose in hand. Having a relatively long pedigree, this approach received a considerable fillip with the publication by Gosta Esping-Andersen of his work related to a sample of western nations (Esping-Andersen, 1990). The basis of his typology was the nature of class conflict in western, industrialised countries and the resolutions that determined the extent to which access to welfare goods was separated from labour market position. His concept of de-commodification thus included the extent to which welfare states provided socially acceptable standards of living independently of participation in economic activity, on the eligibility criteria and on levels of benefits or provision. It can, therefore, be seen, as Bonoli (1997) points out, to incorporate elements of both the scale and the nature of state intervention. On this basis Esping-Andersen proposed three, distinct regimes. Liberal regimes, of which the US could be viewed as the archetypal case, take a minimalist position, providing welfare as a last resort, in the event of the failure of markets to provide, generally means-tested and to a minimum level. In conservative-corporatist regimes - West Germany being archetypal - there is no great attempt to modify status differentials, welfare being typically delivered through or in relation to occupations; the family and the Church are key elements in welfare provision. Finally, social democratic regimes - here, Sweden is archetypal - are based on broad consensus across social classes, with universalist principles aimed at achieving high levels of de-commodification and equality; here, the state is the first, not the last, resort.

How does this typology help in the identification of the principal characteristics of welfare policies in the new industrialised countries of south and East Asia? In fact, not only has it been recognised that Esping-Andersen's three worlds are insufficient to encompass the full range of regimes in western countries, with the case being made in particular for a fourth category relevant to Mediterranean Europe, the Latin rim (Leibfried, 1993), but also that the eastern industrialised countries - Japan and the newly industrialised societies of south and east Asia - constitute quite a different case to any of them. (Gould, 1993; Jones, 1993; Kwon, 1997).

Whereas from the perspective of the west these economies have sometimes been thought of as examples of rampant capitalism they do not match Esping-Andersen's liberal type in that they are characterised by high levels of central direction and low levels of individual rights (Jones, 1993). The absence of any developed sense of individual rights or equity also rules out a social democratic model, with the nearest model appearing to be the conservative-corporatist. But, such comparisons miss the fundamental point: the Esping-Andersen typology is based on historical resolutions in Europe that have no direct parallels in the very different historical circumstances of south and east Asia (Kwon, 1997). A specific difference is that, unlike European corporatism - that particularly underlay the Bismarkian social programmes in Germany - social policies in the Asian industrialised economies have generally not been introduced against a background of threats from the working class (Kwon, 1997). Rather they can be viewed as a reflection of the perception of what has been necessary in order to ensure economic growth. The political strategy, in other words, was driven, pragmatically, by considerations of what policies, with respect to welfare, were deemed most appropriate for achieving increased national prosperity. This was carried out against the background, in many Asian countries, of Confucianism in which it is the group - the family, the firm and the nation - which takes precedence over the interests of the individual. Such systems are highly structured such that duty is owed upwards and responsibility down, the family is the basic building block of a grand, national corporation which is characterised by authoritarianism, the incorporation and neutralising of opposition, and subservience to the needs of the whole with the result that welfare policy 'has been more strongly shaped by the developmental priorities of politically insulated states than by extra-bureaucratic political forces' (Deyo, 1992, p.304). In general this has meant that the decommodification of welfare has not been greatly pursued so that social expenditures have been restricted in order that the 'primary goal of national policy' (Ku, 1995, p.360) would not be starved of the necessary resources.

Family, Gender and Welfare Regimes

In his work Esping-Andersen draws attention to the importance of taking 'into account how state activities are interlocked with the market's and the family's role in social provision' (Esping-Andersen, 1990, p.21). Feminist scholars have demonstrated that critical to developing an analysis of the part that the family plays, and is expected by the state to play, in welfare provision is a consideration of the role and needs of women.

In contributing to the development of comparative perspectives, feminists studying welfare regimes (for example, Lewis, 1993; Orloff, 1993; Sainsbury, 1994; Pascali, 1997) have highlighted the limited potential of the Esping-Andersen formulation (including the incorporation of the Asian variant) for analysing the role of the family and of women. They have argued that the class redistribution focus of Esping-Andersen's approach cannot fully accommodate the necessary comparative examination of the contribution of both unpaid and paid labour to welfare states and welfare provision.

From this literature, to date there are two formulations that have attempted to build critically on Esping-Andersen's work. Orloff (1993) has developed a framework that she suggests should be used to compare welfare states in order to accommodate an analysis of the contribution of women and the family. The framework comprises five criteria: the way in which state-market-family relations deliver patterns of social provision; an approach to stratification which embraces the impact of state provision on gender relations, including the treatment of unpaid and paid labour; an examination of social citizenship in order to identify the differential effects of benefits on men and women; differential access to paid work; and, the capacity which exists to form and maintain an autonomous household.

Siaroff's approach (Siaroff, 1994) has taken as its starting point the ways in which OECD welfare states are meeting women's needs. She uses three criteria to measure, on a scale of 1-3, the extent to which each regime meets fully or partly the needs of women: the family orientation of policy; the ease with which women can work on equal terms with men; and, the parent who receives benefits for the children. Her work has generated a cluster of four regimes. Three fit Esping-Andersen's formulation and the fourth 'late female mobilisation welfare states' is used to identify welfare regimes which neither encourage women's work nor support women's caring (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Siaroff's four welfare regimes

| Welfare Regime Type | Typical country | Extent of meeting women's needs |

| Liberalism | USA Australia | 2 |

| Conservatism | Germany France | 2 |

| Social democratic | Sweden Denmark | 3 |

| Late female mobilisation | Japan Spain | 0 |

Source: adapted from Deacon et al. (1997)

The potential contribution of these two approaches to the development of comparative analyses is as frameworks to facilitate the exploration of the ways in which the family, in its various formations, contributes to welfare provision. In focusing on the family in this way the gendered divisions of paid and unpaid labour as well as family responsibilities become key characteristics of welfare regimes.

In considering the current situations of Malaysia and Britain the adoption of such approaches need to be considered with some caution with regard to the context of contrasting historical, social and cultural understandings of family, state and gender. Yet even with this caveat, they may have a potential to provide an initial orientation to the meanings which welfare regimes attach to family life and associated gender relationships. Such an orientation is particularly relevant to societies which in responding to economic and social change are faced with intended and unintended consequences for family formations and values. Of particular relevance here are the ways in which changes in the labour market and in levels of public welfare expenditure impact on women and the family and the relationship between men and women as workers, citizens and family members.

The Foundations of Welfare Policies in the Two Countries

In this section the origins and underlying philosophies of the welfare systems in Britain and Malaysia are presented. Whereas there were common elements, for example deriving from their colonial relationship, it begins by emphasising their different approaches.

It could be argued that in the early post war years Britain's welfare policies developed elements of all three of the Esping-Andersen regimes a mix of minimalist, means-tested benefits and universal benefits, some benefits tied to occupation, and the nuclear family, with particular welfare roles expected of women, underpinning the system. The Malaysian case, in contrast, can be usefully depicted in relation to a regime type in which the development of welfare has been greatly influenced in ways seen by governments to be functional to the needs of an economy growing rapidly to achieve the status of an advanced industrialised country. In short, it broadly conforms to the model characteristic of the newly industrialised countries of south and East Asia.

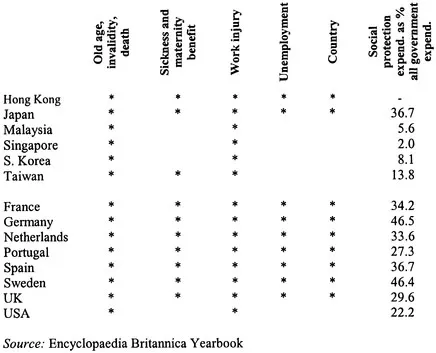

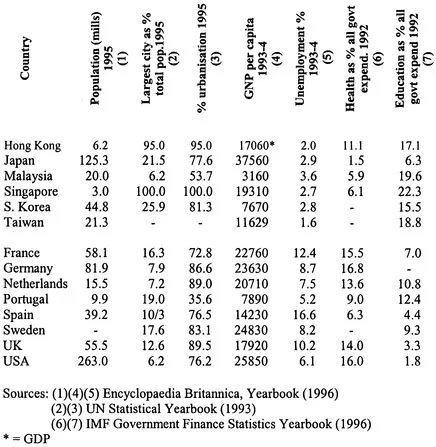

The contrast can be seen, even decades later, in data describing the nature and scale of social policies. Britain is representative of a western tradition in which a wide range of social protection measures consumes a large (between a quarter and a half) of all government spending, with Malaysia typical of a lower spending, eastern tradition (Table 1.2). This contrast is maintained in health care spending, but in education spending the positions are reversed: by western standards the Asian economies have invested heavily in the development of human capital as a fundamental part of their strategy to achieve rapid economic growth (Table 1.3). On this view, then, Britain and Malaysia are not at different stages in social welfare development but are representative of fundamentally different approaches.

Table 1.2 Social protection measures (1995) and expenditure (1992)

Britain The Beveridge report and Keynesian economics - products of Liberal Collectivism - were the foundations on which the welfare state was established in post war Britain (Ginsberg, 1992). Beveridge argued that the State should extend its responsibilities in order to offer protection to citizens against social need in all its forms. It was a model much influenced by the way in which the British war time government had mobilised the nation, relying on direct state provision of benefits and services with little emphasis on contributions from voluntary and private commercial organisations (Dunleavy, 1989). From 1946-1948 a range of state agencies was established. Funded from general taxation, they included: a national health service, free at the point of delivery; a state education system for all 5-15 year olds; a national state funded insurance and assistance scheme for those who were old, unemployed, disabled or sick; public housing; and local authority health and welfare provision for children, families and older and disabled adults in need of support and protection.

Table 1.3 Demographic, economic and welfare indicators

The welfare state created in Britain at this time was celebrated by a leading social policy academic as adding a social dimension to civil and political citizenship (Marshall, 1950). Through its commitment to meet basic social needs it provided a guarantee of social rights. As Alcock summarises it: 'The welfare state of the post war period appeared to be the embodiment of social citizenship and to have created the basic framework for a new role for the state as the provider of social services' (Alcock, 1996, p.8).

The welfare state was embedded in, and seen to be contributing to, a Keyn...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Foreword

- 1 Britain and Malaysia: the development of welfare policies

- 2 Work and social security provision in Britain: seeking a third way

- 3 Social security policies in Malaysia

- 4 For richer and poorer? Pension policy in the United Kingdom

- 5 Formal old age financial security schemes in Malaysia

- 6 Managing a mixed economy of social care: community care in Britain

- 7 Community care in Malaysia

- 8 Britain's evolving health policies

- 9 Getting well in Malaysia

- 10 Housing policy in Britain

- 11 Public housing policy in Malaysia

- 12 Crime and penal policy in Britain

- 13 Imprisonment in Malaysia