![]()

Part I

How Alexander Pope Became a Poet

![]()

Chapter One

On Being a Papist

Alexander Pope was born on Monday 21 May 1688 at 6.45 pm when England was on the brink of a revolution. Much of his character and life were to be determined by that revolution and by the decision his father had taken to become a Roman Catholic. From birth he was destined to be an outsider.

Mr Pope, whose first name was also Alexander, probably converted to Catholicism when he was a young man, during the early, easy years of the Restoration. Later, during the agitated reign of James II, he bought and read all that was being written on both the Protestant and Papist sides but, when he had finished reading, he found no way he could change his mind.1 After the revolution Mr Pope's decision to remain a Catholic made him a religious and political outcast, ever careful to avoid attracting the attention of the authorities, or of hostile neighbours. He had virtually no civil rights. In modem terminology he was a non-person. His son would live all his life as a potential enemy alien in the land of his birth.

Mr Pope was an unlikely martyr. He was not reckless, impractical, or an obvious rebel, but he thought for himself and his education in a puritan setting failed to indoctrinate him against the Church of Rome. He was born post-humously in 1646, the year in which Charles I lost at Edgehill and surrendered to Parliament. His father had been the energetic and zealous Rector of Thruxton in Hampshire, who once rejoiced in bringing the daughter of a local Catholic landowner 'unto our Church of England.'2 After the Rector's death his widow returned with her newborn child, and his brothers and sisters, to Micheldever where her father, the Rev. William Pyne, had his parish. The theological views of Mr Pope's grandfather can be guessed at from the fact he kept his living throughout the Cromwellian era.

Mr Pope rejected his family's Protestant faith, but not the Protestant work ethic. He grew up to be industrious, thrifty and ambitious. At the beginning of 1688 he was a successful linen merchant. Twenty years earlier he and his brother William had used the few hundred pounds they had inherited from their father to start a business, dealing in 'Hollands wholesale.'3 After a while William had disappeared and Mr Pope carried on alone, selling cloth in England, then expanding his operations so as to export goods to the American colonies, steadily increasing his initial capital of £500 until he was worth several thousand.4 In this respect he was a typical member of the rising, mercantile, middle class.5 He was also a typical and worthy descendant of men who were hard working and knew how to make and look after money, in whatever field they laboured – and, as we shall see, his son would carry on this family tradition.

Since the sixteenth century the Popes had moved a few steps up the social ladder with each generation. The first one we know anything about was a blacksmith in Andover. He did well enough to enable his son Richard to buy The Angel Inn, the leading hostelry in the town. Richard prospered, played an active part in Andover's public affairs and sent his son Alexander to Oxford. This was the Alexander who became the Rector of Thruxton who, dedicated to his calling as he was, still looked after his worldly interests.6 Before his sudden death he was on the brink of securing an income of more than £400 a year, which was six to eight times as much as the average parson received.7 It was in order to obtain the standard of living the Rector would have enjoyed, had he lived, that Mr Pope had gone into trade. When he did so he did not expect to find that his religious convictions would get in the way of his commercial success.

He married twice, choosing Catholic women on both occasions. His first wife died in 1679, leaving a daughter Magdalen who survived, and a son (another Alexander) who died three years later. While Mr Pope looked for a second wife he had sent his children to be cared for by his sister, not minding that her husband was the Anglican Rector of Pangbourne. When he remarried Mr Pope chose Edith Turner, a plain, affable woman, three years older than himself. She came from a highly respected, middle class family in Yorkshire, but was unlikely to inherit much money because she was one of seventeen children who lived to maturity. There were fourteen girls, half of them Protestants. Like her husband, Edith never let religious differences prevent her getting on with her relatives.8 One of her Catholic ancestors was Margaret Clitherow who was canonized, after embracing an excruciating martyrdom in 1586.9 Mrs Pope, however, was simply a devout woman who later won the respect of Jonathan Swift because she was that rare being, 'a good Christian.'10

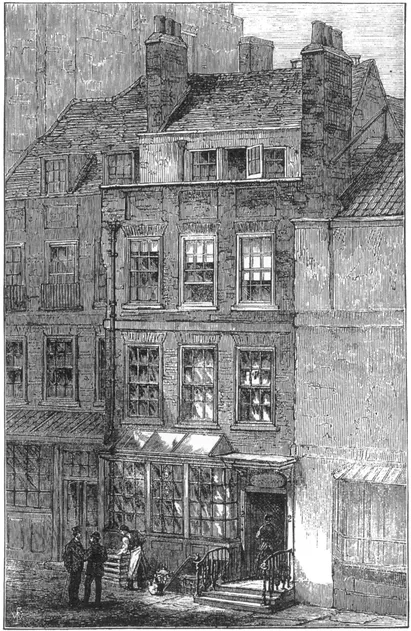

Mr Pope took Edith and Magdalen to live in the house he had rented in Plough Court, off Lombard Street in the City. His landlord John Osgood was another linen merchant.11 He was also a Quaker but this did not stand in the way of his having a cordial relationship with his tenant. The Popes and the Turners were perhaps unusual in numbering both Catholics and Protestants in their families, but they were not unusual in being able to get on with people from other denominations. During the reign of Charles II Protestants often lived and worked alongside Catholics without friction, turning a blind eye when they knew their neighbours celebrated Mass, even though this was against the law. Catholics were in the minority, amounting to less than two per cent of the population. As individuals practising their faith, they were not feared. Trouble arose, when it did, because Roman Catholicism was not just a matter of private belief. It was also a political system which English Protestants were determined should never be re-imposed on them.

1.1 Pope's birthplace, 2 Plough Court, London. From The Illustrated London News, 7 December 1872

Charles II was a Catholic but was so discreet that most of his subjects never realized he was one, still less that he was financed by the Catholic king of France. No one was in any doubt, however, about his brother James II.12 He paraded his faith. He came to the throne in 1685, the year in which Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, causing thousands of Huguenots to flee the country, many of them crossing the Channel. Even as Londoners read in the Flying Post of the persecution of French Protestants, they watched with dismay as James celebrated Mass openly in the royal chapel and received the Papal Nuncio with all due ceremony at court. James set out to restore full civil and religious liberty to Catholics and bring them back into public life, but only succeeded in arousing that terror of the Church of Rome as a political force which never lay very far below the national consciousness. Nonconformists joined with Anglicans to defend the cause of Protestantism. By the time the King began appointing Catholics to military and civil offices under the Crown, he had appalled the entire secular and clerical establishment. Within weeks of Alexander Pope's birth England's ruling class had decided that if James was prepared to undo the Reformation, they were ready to undo the Restoration.

Outside the house in the City where the infant lay in his cradle, London was in a state of continual uproar in the second half of 1688, On 7 June crowds lined the banks of the Thames, weeping and praying, as they watched William Sancroft Archbishop of Canterbury being taken to the Tower on James's orders. On 30 June Sancroft and his six fellow bishops were tried in Westminster Hall, on a charge of sedition. The momentous trial went on all day and no one could predict the verdict when the jury retired. After debating the case until dawn, without light, food or water, the jurors emerged and declared the prisoners 'Not Guilty'. Whereupon those same crowds got drunk, surged through the streets and, that night, lit bonfires on which to burn elaborate effigies of the Pope. Meanwhile, Admiral Herbert, disguised as an ordinary seaman, had sailed to Holland with a letter signed by seven representative gentleman, inviting William of Orange to come to England. On 5 November William landed at Torbay.

During 1688 wild rumours swept through the capital. The first of these was that James's son and heir, born prematurely on 10 June, was a changeling, carried into the Palace by Jesuits determined to ensure a Catholic succession. On another occasion, candles glimmered in every window throughout the hours of darkness, while hastily summoned trained bands lined the streets with pikes and muskets because hundreds of pamphlets had appeared during the day, warning everyone that Irish troops were about to descend on London, intent on murdering every Protestant they could find. No one came.

Yet the truth was just as strange as these fictions. On the morning of 11 December the King's attendants at Whitehall had gone into his apartments as usual, only to find he had disappeared. James had fled by a secret passage in the middle of the night, intending to seek refuge with Louis XIV. By that time he was already breakfasting at the Angel Inn at Andover before continuing on his way to the coast.

The news of James's abrupt departure was the signal for widespread rioting in the capital. Mobs chanting 'No Popery' went in search of Jesuit priests, stopping and interrogating all known Catholics. Zealots burned down the King's Printing House, which had published the Papist propaganda studied by Mr Pope and, joined by opportunistic riff-raff, sacked the Spanish Embassy and destroyed all the Catholic places of worship. As the fires burned that night, Mr and Mrs Pope could see from their windows in Plough Court how the sky glowed red, and could hear the sound of falling timber and masonry as the mob tore down the nearby chapels in Lime Street and Bucklersbury.

There was no bloodshed however. Actually the crisis was over. Even as James II left London, William of Orange was approaching it. He was warmly welcomed when he arrived. It was decided that James had abdicated and in February 1689 William and his wife Mary (James's daughter) were declared joint rulers of England.

Mr Pope 'left off business when King William came in.'13 With the departure of James his whole life changed. Perhaps his personality changed as well. We can only guess at the vigorous, confident entrepreneur who was on his way to making a fortune in 1688. All the anecdotes about him date from a later period and show us a muted figure, anxious not to give offence, even in trifling matters. Magdalen, for instance, describes how he intervened when her stepmother was about to pay a lace-maker. Mr Pope insisted that his wife give the woman the going rate of twelve shillings for a piece of work she was doing, even though the two ladies had agreed that, as an old customer, Edith should continue to pay ten shillings, as she had done before a price increase.14

When Alexander Pope wrote about his childhood he was specific about his father:

For Right Hereditary tax'd and fin'd,

He stuck to Poverty with Peace of Mind;

And me, the Muses help'd to undergo it;

Convict a Papist He, and I a Poet (Ep. II. ii. 59-62)

Pope used words precisely so we should pay attention to th...