![]()

1 The heartbeat of fandango

Son jarocho practitioners understand the craft of making music beyond the mere production of organised sounds. Their performances are essentially integrated by dancing, singing verses and playing specific musical instruments. As any other form of music making, these performances can be framed as spatio-temporal sets of actions. Son jarocho dance, verse and instrument playing are articulated at the traditional celebration of the region of Sotavento called fandango.1 The term fandango has been widely used in the Americas and the Iberian Peninsula since colonial times to designate various types of dance and music. Throughout this book fandango refers to the popular celebration in which son jarocho is practised. This use of the term has been traced to the eighteenth century in archives of the Inquisition in New Spain that portray a mulato (a man of mixed ancestry) who sang verses, depicting him as ‘very fandanguero’ (Pérez Montfort 2003: 39, my translation; see also Delgado Calderón 2004). The adjective fandanguero was used in the context of an accusation of invoking demons through music and dance. The demonization of fandango gradually faded as it became consolidated as a popular celebration, but this practice has historically carried with it meanings that oscillate between the sacred and the profane (García de León 2009: 18). There is a ritualistic attitude towards this way of making music that takes the form of a collective belief in the practice, a compliance with the process through which this performance unfolds.

Fandango is a celebration in which the manipulation of artefacts produces various forms of embodied and collective engagement. In the following sections I focus on the motion that takes place as performances unfold. My aim is to illustrate how these ways of enacting a musical practice produce specific spatial and temporal dynamics that stem from continuous movement during performances. To give an account of these processes it is necessary to examine how musicians, dancers, instruments, verses, dance steps and other instances are in motion during performances. But first I will discuss the cultural significance of the tarima, an artefact that materialises and articulates collective action at fandangos.

Tarima

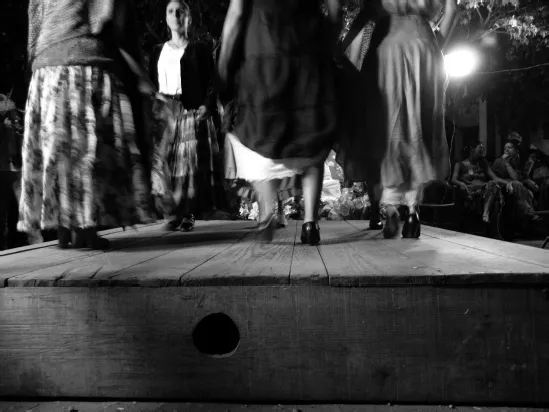

The seamless integration of dance, instrument playing and verses that takes place at fandango acquires its full collective meaning by being enacted in relation to a stomp-box called the tarima. The tarima is a platform made of several wooden planks that together form a large box on which practitioners dance. It rests on its sides, which have holes that enhance the resonance produced when dancers stomp on it with hard-soled shoes. While it may look like a rustic stage, this platform is not used as a surface on which entertainers become visible, and thereby differentiated from an audience. The tarima is a percussive instrument that rhythmically structures the unfolding of performance. Acoustically, the tarima is built with specific material characteristics in mind: its top must be firm and resistant as it will be hit simultaneously with the hard-soled shoes of at least six dancers. At the same time, it must be flexible enough to cushion the strikes and to resonate like a deep stomp-box. Tarimas made of oak tend to be hard and sturdy; mahogany offers a good balance between resonance and solidity (although it can be expensive); and pine and mango tree are also good materials, but are only available in certain places. The physical qualities of the tarima are relevant for the way in which fandango unfolds, and for the embodied/mental schemata of dancers and musicians.

The relevance of the tarima can hardly be exaggerated, as it constitutes the heartbeat of fandango. It is by far the biggest instrument in the performance, and its commanding resonance marks the beat. Llevar el golpe (to carry the beat) is the duty of dancers, which refers to the ability to sustain a steady pulse and to articulate distinct rhythms for each theme. Practitioners appreciate it when dancers highlight the differences of every piece of the repertoire and bring rhythmic variety by dancing each son2 with a distinct cadencia.3 For this reason, skilled dancers pay attention to the volume and timbre of the tarima on which they are dancing in order to regulate their steps as the performance unfolds. Dancers do not only display their skills through the elegance of their movements, but primarily through their competency as rhythm makers, as percussionists. For instance, when the performance is building momentum there are peaks in which dancers aprietan (tighten it up) by stomping more effusively, inducing the musicians gathered around them to play with even more intensity. It is highly emotive when everyone around the tarima moves at the same pulse and is completely focused on the same rhythmic ‘feel’. Practitioners commonly describe this effect as playing amarrado (tight, tied up), which is a way of saying that participants and instruments hang together and resonate around the same tarima. Here Marco,4 a practitioner who has been making son jarocho in Sotavento and different cities in Mexico for decades, explains the significance of tarima in the context of fandango:

This celebration [fandango] is something close to a ritual; it is a space. Look, it is an incredible thing when you go to a ranchería [a small rural settlement] and people take the tarima, either from the place in which the celebration happens, or from a different place. Some carry the tarima and say ‘Hey, Don Fulanito,5 where are we placing the tarima?’ And Don Fulanito says ‘Eh … let’s place it there.’ And that place, that little area, becomes a sacred place, because wherever you place that thing … I’m going to say it in an ‘ugly’ way, because if you look at the tarima without this understanding, it is just a mouldy piece of wood, isn’t it? But wherever we place that piece of wood, right there, that very place becomes a magical thing, because around that simple piece of wood everything happens. Romantic relationships come! From there comes the possibility for me to sing the verse I learnt! The possibility that I meet other people! That I meet with that dear friend I haven’t seen in a long time! The possibility of meeting that great jaranero and playing beside him!6 That thing, all the respect, all the mysticism that happens around that piece of wood, happens only because everyone keeps a ritualistic attitude. Do you see?

Figure 1.1 Tarima and dancers

Regardless of austerity or opulence, it would be unthinkable to have a fandango without a tarima; its presence is a basic condition for the celebration to take place. This collective achievement that Marco refers to as ‘ritualistic attitude’, this ‘practical belief’ (Bourdieu 1990: 68) in the activities that take place, is enacted around this artefact. Its significance in the context of fandango reveals how materials enable and constrain the unfolding of events and, more generally, how their materiality is a constituent of the social (Schatzki 2010a: 123). An example of the relevance of the tarima comes from a fandango that I attended in San Diego, California. We were not celebrating anything in particular, and simply decided to meet up for the mere interest of playing and dancing together. Helena, a friendly jaranera who has been very active at the son jarocho scene of California, picked me up in East Los Angeles and we headed south. A few hours later we arrived in Balboa Park in San Diego and started walking around, looking for the fandango. The Facebook invitation indicated that we were meeting ‘by the fountain’, but we soon realised that it was going to be a bit complicated to find the fandango as there were several fountains in the park.

We spent some time watching people walking their dogs, and kids eating ice cream, until we saw a girl with a jarana hanging from her right shoulder. She was also looking for the fandango and had already spent half an hour looking for familiar faces. We saw a small group of people gathered by one of the fountains, and by sunset we had formed a group of around twenty people switching between English and Spanish, tuning instruments and eating snacks. One hour later, we all had our instruments in tune, avoided switching languages (because of linguistic fatigue) and had already eaten enough snacks. I was holding my instrument with impatience, wondering when we were going to get started. Surprisingly, nobody dared to start playing and there was no need to ask why: the person bringing the tarima had not arrived yet; thus, playing without it would be like attempting to start a football match without a ball. Two young men finally arrived carrying the tarima, apologising for being late and recounting the mechanical problems they had had with their truck. There is no fandango without the tarima because its use is a condition for the event to occur.

The spatial dynamics around the tarima are meaningful because this artefact is the epicentre of the action. It is commonly understood that the hosts of the fandango, locals and the most knowledgeable musicians stand closer to the tarima because they can be heard clearly by the dancers, who in turn develop the groove with their stomping. Traditionally, it is the requintero7 (a person who plays the requinto, also called guitarra de son)8 who stands close to the edge of the tarima and leads the fandango by deciding what sones from the traditional repertoire are going to be played, as well as their sequence, tempo, key, mode and cadencia. Being physically positioned close to the tarima is crucial to influencing dancers’ stomping and, most importantly, to deciding when to begin and finish a son. The spatio-temporal order maintained around the tarima is not explicit because it is presumed by practitioners; and, in the case of new apprentices like me, it suffices to imitate what the most experienced do. The mechanisms of these tacit understandings can be better appreciated by analysing the way in which fandango unfolds.

A festivity unfolding

I attended a fandango in Chacalapa, a rural town in southern Veracruz. The celebrations at this particular location are famous among jaraneros to the extent that conversations about them acquire a mythical character. Prior to that event, I spent a few weeks hanging out with jaraneros of this region, particularly around Cosoleacaque, Chinameca and Chacalapa. These towns have been historically connected by trade, roads and people who go back and forth to shop, visit relatives or catch buses to larger cities. As other son jarocho practitioners, I travelled to workshops, fandangos and other gatherings by bus, taxi and privately owned vans that function as public transport. On these trips I visited groups of young jaraneros who organise son jarocho workshops and occasionally gather in the afternoons to play casually when the sun sets and the heat recedes. My expectation regarding the fandango in Chacalapa was growing as they reiterated how these events were the ‘real thing’, just like ‘those made many years ago, when the old jaraneros were younger’.

One afternoon I was travelling by taxi from Chinameca to Chacalapa with José, a young jaranero with whom I was going to the fandango. José had kindly offered to host me that night and we were making a quick stop at his house before heading to the celebration. Inside the house was a large room divided into three sections; the kitchen was on my right-hand side, where José’s mother and her neighbour were having a lively conversation while washing dishes. After greetings and introductions I went to the opposite side of the room to drop my backpack. The left end of the room was a bit darker, but I noticed a hammock bouncing slowly. A young man said ‘Hi’ and then started playing chords with a small jarana. I introduced myself and sat down on a couch nearby.

‘Nice jarana’, I said.

‘My father made it, I’ve been struggling to get it in tune the whole afternoon’, he replied and then tried a few chords as if testing the tuning, slowly strumming the strings absentmindedly without any regular rhythm.

He continuously stared at a fixed point on the ceiling and never turned his head to the jarana or to me; I then realised that he was blind. He twisted one of the wooden tuning keys because it did not sound quite right yet. He tested it again, but this time he strummed chords in a steady manner, as if playing a son. That sounds like ‘El Pájaro Cú’, I thought.9 How did I recognise that son? Habits grow quickly in the field, and I was attaining the capacity to recognise musical pieces not by their melody, but by their rhythm, phrasing and chord progression. The smell of beans and fried pork filled the entire room.

‘My mum says dinner is ready’, José said, and when I turned to the kitchen I saw his mother walking towards the door.

‘Have a good time, guys’, she said in a rush. Then she turned to me: ‘Please make yourself at home.’

José and I sat and ate silently; it was already dark and we were...