![]()

1

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

“In a sense, each of us is an island. In another sense, however, we are all one. For though islands appear separate, and may even be situated at great distance from one another, they are only extrusions of the same planet, Earth.”

—J. Donald Walters

1.1 Water resources on small islands

Over 100,000 islands are homed by planet Earth, which account for approximately 20% of global biodiversity (Richardson 2017). They are particular because of their uniqueness, which is further characterized by their size, shape and degree of isolation. Because of this, they have become ecologically and culturally important. Nevertheless, these characteristics also contribute to their fragility and vulnerability.

Islands around the world vary in size, geology, climate, hydrology, type of water resources, distance to the mainland, etc.; but they do have one issue in common: water stress problems and the consequent challenges that these have brought up. According to Bruce et al. (2008), islands are characterized mainly by the limitation of their water resources, which is a direct result of their insular condition, as well as their geological formation. Furthermore, among all islands, small islands are considered one of the most vulnerable human and natural systems, because of their size, limited natural resources, their remoteness, rapid population growth, and climate variability. These small islands, as well as small island states and small island developing states (SIDS) are located usually in the tropics and subtropics. In general, they consist of regions of the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans, as well as the Caribbean and Mediterranean Seas (Nurse et al. 2001). Even though the different types of islands are not considered as a homogeneous group, they do share their vulnerability.

Most of small islands are rich in biodiversity, resulting in endemic flora and fauna. However, they tend to have relatively few natural resources. The resulting scarcity of water resources could be attributed to the climatic and physical conditions of each specific island. For instance, the amount of freshwater available in island communities depends on a delicate balance between consumption and climatic, hydro-geological, and physiographic factors (White and Falkland 2010). For many islands, the main problem is their semi-arid conditions, resulting in low precipitation levels. For others, such as volcanic islands, the lack of freshwater has been a persistent problem, depending on their availability (only) on their rainy seasons (d’Ozouville et al. 2008a). Nevertheless, even in islands with high precipitation rates, water resources are considered scarce due to the limited capacity of storage in the dry seasons, and their relative limited surface area (Hophmayer-Tockich and Kadiman 2006). Consequently, a serious and restrictive factor relies upon the availability of freshwater resources in the majority of inhabited small islands (Kechagias and Katsifarakis 2004).

Furthermore, many small islands worldwide are completely arid and their water resources are further limited. These islands are also experiencing excessive population growth and densities, which increase water demand and potential pollution of their water resources (Tsiourtis 2002). According to the Asian Development Bank, the size of islands limits their availability of natural resources, including water. Because of this water scarcity, the local economic growth is in many occasions restrained, which is mostly the tourist industry. Tourism is the most important motor of the economy for some islands (e.g. Barbados, Bahamas, Malta, Galápagos, etc.), and for others is the second most important economy (e.g. Maldives, Western Samoa, etc.) (Ghina 2003). Nonetheless, the assurance of their development and success of economic activities depends greatly on the preservation of their scarce natural resources. The main characteristics of small islands include this dependence on tourism for their economic prosperity, as well as their limited infrastructure, low financial means, lack of skilled human resources and high population growth (Ghina 2003).

The freshwater availability is mainly attributed to the geology and formation of the different islands. In case of volcanic islands, the lack of freshwater is significant. Their main source is brackish groundwater, which is the mixture of intruded seawater and rain in the basal aquifers (d’Ozouville et al. 2008a). Furthermore, their water availability may also vary depending on the levels of precipitation, making some regions more water scarce than others. In other type of islands, the main source is groundwater, such as in the Caribbean Islands like the Bahamas, Barbados, Jamaica and St. Kitts. On the other hand, other islands have surface water as their main supply, such as St. Lucia and Trinidad & Tobago (Ekwue 2010). Several Mediterranean islands, such as the Greek Aegean, as well as Malta, use desalinated seawater as their main source (Kondili et al. 2010). In extreme situations, freshwater is imported on tanker ships from the mainland like in the Bahamas, Antigua, Mallorca and some Greek Islands (UNESCO 2009). According to White and Falkland (2010) there are about 1,000 populated small islands in the Pacific Ocean, which have their main source of freshwater from groundwater, but it is limited and compromised also by pollution. In addition, the intrusion of salty water into groundwater resources is a common and major problem (Khaka 1998). This intrusion affects not only the quality of the water but also the quantity, since the transition-gradual mixing zone of fresh and salt water is extensive (Gingerich and Oki 2000). Besides, these scarce water resources could be further threatened by climate change, climate variability and consequent rising sea levels (Bruce et al. 2008).

According to Donta and Lange (2008), small island states are also restricted by the lack of organizational expertise, deficient financial infrastructure, few incentives for water harvesting, old and unreliable water infrastructures leading to high leakage levels, and absence of effective water pricing and cost recovery systems. Due to all these issues, water supply alternatives in small islands need to be explored (Gikas and Tchobanoglous 2009). The literature points to several technical options to increase availability of water, especially addressing desalination (Kondili et al. 2010, Castillo-Martinez et al. 2014). Also, several environmental measures have been suggested by Hof and Schmitt (2011) to create awareness in order to reduce urban water consumption, as in the case of the Balearic Islands, as means to reduce the need of more water supply. However, each island is particular and therefore the set of solutions may vary according to each study area.

1.2 Tourism influence on small islands

Tourism in many tropical islands has increased dramatically over the last decades. It is the most dominant economic sector in several island states and other small islands, such as in the Caribbean (Charara et al. 2010). Even though tourism is a major source of income and employment for many islands (Briguglio 2008), it has been amongst the main causes of environmental degradation which exerts a significant pressure on natural resources, such as water. According to Mangion (2013), tourism is the main cause of extreme demand for diverse natural resources, inflicting environmental threats and high infrastructural costs, which unfortunately are often not taken into account. Even though tourist visitors contribute significantly to their economic growth, they often require services and facilities that produce an unsustainable balance between infrastructure and natural resources. Therefore, a massive construction due to tourism has been identified, as well as an insufficient control of urban planning, such as the case of many of the Mediterranean Islands (Essex et al. 2004).

1.2.1 Water use related to tourism

Despite the fact that islands have limited natural and water resources, the expansion of tourism to these type of destinations over the last 40 years has been overwhelming (Essex et al. 2004). As a result, tourism growth has caused in many island states, deficiencies in the provision of water supply and sewerage systems (Bramwell 2003, Marques et al. 2013). In addition, tourism increases overall per capita water consumption, concentrating it in time (often in the dry and high season). The proportional increase of water demand is also amplified by the growth of local population, which needs to provide facilities and services to satisfy tourist visitors. For instance, in some areas of the Mediterranean Islands, the ratio of local population to tourists may change over the year, reaching in some cases more than one to six. Specifically, in the Balearic Islands, water use during peak months of tourism (e.g. in July 1999) was equal to 20% of the water use of the entire local population for the whole year (Gössling et al. 2015). According to Mangion (2013), a tourist in Malta consumes on average three times more water than a local resident, creating a challenge for water supply utilities to be able to comply with these elevated rates (Briguglio 1995).

Water consumption in the tourism sector is varied. It comprises of several activities such as: bathing and showering, toilet use, golf courts, landscaping, spas, wellness areas, swimming pools, as well as food and fuel production. In addition to these uses, hotel water consumption includes recreational activities such as sailing, diving and fishing (Gössling et al. 2012). In consequence, the proportion of water consumption by the tourist sector can be as high as 40% (e.g. in Mauritius) over the resident average water use. This number tends to be higher in areas where water is scarce and the number of tourists is even higher.

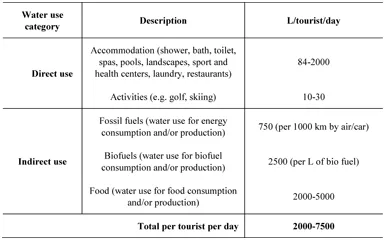

Table 1.1 Water use categories and estimated use per tourist per day

Tourism water use tends to increase with hotel standards, increased water-intense activities, as well as with the growth rates of tourist visitors. Even though the water consumption in hotels has been already recognized as high, it can result in even greater quantities in luxurious hotels. This type of hotels use significant amounts of water for recreational activities such as swimming pools, golf courts, extensive gardens, etc. Gössling (2001) reported that the variation on water consumption is directly related to the hotel category. For instance, in Zanzibar, the average water demand in guesthouses is 248 L/tourist/day, which is significantly lower than that in five- star hotels (931 L/tourist/day). According to Deng and Burnett (2002), the average water use in five-star hotels is approximately 5 m3/m2 of hotel area, while in four-star hotels and three-stars hotels are 4 and 3 m3/m2, respectively. According to this study, the main water consuming activities are: (1) garden irrigation, (2) swimming pools, (3) spas and wellness facilities, (4) golf courses, (5) cooling towers, (6) guest rooms and (7) kitchens. Furthermore, indirect water use related to tourism is often not taken into account, but this accounts for great quantities of water as well. Table 1.1 shows the average per capita consumption related to direct and indirect water use in the tourist sector.

In conclusion, the increase in water demand on islands is mainly attributed to the tourist sector. For example, in the Mediterranean Islands an average tourist consumes between 440-880 litres per capita per day (lpcpd) (Gössling et al. 2012), while in Jamaica, Barbados, St. Lucia and the Philippines the reported specific demands are 992, 756, 662 and 1499 lpcpd, respectively (Charara et al. 2010). The locals, on the other hand, consume on average as follows: in Mediterranean Islands 200 lpcpd, in Jamaica 160 lpcpd, in Barbados 200 lpcpd, etc. Because of the population growth and consequent per capita demand, water scarcity and stress is experienced, meaning that (ground) water resources are being overexploited. Overexploitation of aquifers are of great concern, and have been occurring in Malta, Tenerife, among many other islands (Axiak et al. 2002, Guilabert Antón 2012).

1.2.2 Water-related problems in islands and their relevant solutions

The tourist industry presents a significant problem for water supply utilities on islands, since tourist visitors often arrive during the dry season, when rainfall levels are low and water availability is at the minimum level. On islands where tourists are high water consumers, the scarcity problem may be worsened by climate change. According to (Gössling et al. 2012) water demand is likely to increase in the future due to increase in tourist arrivals, higher average tourist water consumption, as well as more water intense activities.

In addition, groundwater resources have become extremely vulnerable to pollution, as a result of poor sewerage and wastewater treatment infrastructures on islands with highly permeable soils (Hophmayer-Tockich and Kadiman 2006). Many coastal aquifers are also exposed to the increase in salinity levels as a result of sea level rise and the overexploitation of aquifers. Because of this, desalination has been considered as a viable option in order to preserve the water resources. However, with this option, energy consumption might increase, as well as environmental effects. Moreover, many areas may not be connected to the electric grid, and therefore the process becomes highly dependable on fuel importation to run generators. Also, this option means a high investment, which many islands cannot afford. Nonetheless, combined grid-renewable energy desalination plants can produce potable water with lower emissions (Gössling et al. 2012). For many islands, desalination is considered as the last resort solution, and other more economical and less expensive water supply strategies are considered first (Hophmayer-Tockich and Kadiman 2006).

Other strategies include demand side measures which aim to reduce the water demand. These include Non-Revenue Water (NRW) reduction, water metering, adequate water tariff structures based on water usage, the use of water saving devices, and wastewater recycling for non-potable use (Sharma 2014). Most of these measures are economical and can reduce notably the water use. Moreover, investment in sustainable technologies, as well as in water conservation and management, are key strategies that may avoid to resort to desalination and other strategies which are not considered so environment-friendly. However, in order to achieve this, strong policies are required, including the use of appropriate economic incentives and adequate water pricing to create environmental awareness and encourage water conservation (Gössling et al. 2012). Also, public information, as well as education are necessary tools for the successful implemen...