![]()

1 Introduction and pre-censuses

Introduction

Mwanza is a regional capital and the second largest city in Tanzania. It is located close to the sources of the White Nile, by Lake Victoria.1 In 2005, we were there to interview a representative sample of households, using census-like methods. Dr Teocratias Rugaimukamu of Dar es Salaam University – Rugai among friends – directed the work, which students and colleagues from the University of Dar es Salaam carried out. Close to the lake, we enjoyed the pleasant climate at an altitude of 1,140 meters above sea level. Further inland it got hotter as we left the main road and drove on steadily rougher dirt roads to reach the most remote villages and farms that lacked electricity and piped water, accessible only by walking. It felt like a trip back through history. People were friendly; both men and women willingly answered the numerous questions asked by our students based on a complicated questionnaire. Curious children surrounded us everywhere.

Interviewing ordinary people in the city itself was not very different. Both the linen hanging to dry on clotheslines and the hens and other small animals in the courtyards were all too familiar from the countryside. However, Tanzania’s second largest city has a middle class of traders, some of them of Indian ancestry, shipping goods in transit to Uganda and other central African countries via the lake. In these homes, our questions were not welcome: “If we answer this, we have no idea where we shall end up”. The students presented their questionnaires in vain and support from university doctors or foreign professors had no effect whatsoever. Why their diaspora had made the Indian traders, fear that the Tanzanian authorities could misuse the information never became clear. Frustrating as it was, the episode clearly demonstrated to students and teachers alike how difficult it may be to carry out formal interviews that are intended to be representative of the whole population. Our respect for the statisticians who have managed to monitor the development of an ever-increasing part of the world’s population grew tremendously.

The English word “census” can denote many types of statistical investigations: industrial censuses, traffic censuses, animal censuses and other types of official counts. This book is about population censuses, which are different from our interviews in Tanzania in important respects. According to a strict definition, there should be national legal authority behind a population census so that filling in the questionnaires is not optional but mandatory for everyone. This secures complete coverage of the national territory, which was far beyond our Tanzania project’s resources. Census enumeration should be performed at regular intervals, but we shall see that a population census must be recognized as such even if it was an isolated event. Other usual elements in the definition of a census are a defined enumeration area, simultaneous enumeration, individual enumeration and publication of the results (Goyer and Domschke, 1983). We met the latter demands in our Tanzanian survey, but our sample was far too small to make it into a population census. Now that data processing of census manuscripts has become popular, the concept publication has changed its meaning – it is the contents of the original manuscript forms rather than quantitative results that are the most important to make available to researchers – often as anonymized data files. The analytical value of such data sets is enhanced if people in the same household were enumerated and their data processed group wise.

The word census stresses the qualitative listing of persons rather than the resulting quantitative aggregates. It is rooted in the Latin word “cencere” which means to assess; the classical Roman censuses were lists made for taxation and conscription. When not qualified, census in this book and in the social sciences more generally means population census. Such qualification is unnecessary in German or Scandinavian where the vernacular for population is part of the words Volkszählung, folketelling (Danish, Norwegian) and folkräkning (Swedish), words stressing the quantitative aspect of census taking. French has the concepts recensement and denombrement, highlighting respectively qualitative and quantitative aspects. In Russian, the word perepis’ [перерис] means “write again” and points to the repetitive nature of census taking. They often qualify the concept with the Russian word for population – naseleniia [перепись населения]. In Old Russian the word was chislo, which simply means numbers and the enumerators were called chislenitsi [counters] and words with the same meaning were used in Tibetan, Persian and likely in Mongolian for those parts of the Mongol Empire (Allsen, 1981: 47). Population censuses have sometimes been combined with agricultural censuses, but more often with a housing census. This is both to ensure that all domiciles are included for enumeration and to provide information about people’s residences.

Onlookers and experts have over time and in different locations alternatively praised the work of census takers and derided it as an unrealistic construction. The Canadian sociologist Bruce Curtis (2001) asserted that the results of 19th century Canadian census takers’ efforts deserved to be called the product of “census makers” – bureaucratic constructions rather than representations of population realities. The opposite end of the scale may be represented by the head of Brazil’s General Directorate of Statistics who in 1875 praised the “glorious mission” of the population census as “so noble that census agents should be considered apostles of civilization, of justice and of the happiness of peoples” (Loveman, 2009: 436). More objectively, it is obvious that population censuses can only report about a limited number of aspects in people’s lives. On the other hand, it will provide information about virtually all enumerated persons living in the country. Many historians are mostly interested in extraordinary events and persons. They will not use census materials because the main aim of censuses is to portray what is typical about a population. This is paradoxical, because how are we to know what is extraordinary without the help the census provides by identifying what is typical? (Marker, 2015: 5).

This book is dedicated to all those census takers who took the trouble to travel to all kinds of places in order to enumerate – in principle – the whole population. Varying social conditions and population groups who resented enumeration for political, cultural or religious reasons or who were simply afraid of increased taxation did not make their work easy. The authorities did not make their task easy either; for instance Nordic censuses were systematically taken in the middle of the winter in order to catch the citizens at home at a time when travel was difficult – also for census takers. Russian census takers reported how they had to fend off packs of wolves with guns or poison in areas which were inaccessible unless the ground was frozen. It has been quite common to ask volunteers to take the census in order to avoid paying for the enumeration work. While today’s census questionnaires exist in many languages, the forms used in previous centuries were only printed in the national vernacular and had to be filled with information given by ethnic minorities in a language which was not always familiar to the notaries. It has become common to distribute the census forms by mail, sometimes also over the Internet. Some countries have replaced the questionnaire-based census partly or entirely by having computer programs instead extract and combine information from population registers.

The pivotal person in the history of the population census is the Belgian multi-disciplinary scientist Adolphe Quetelet with his taking of censuses in Brussels and the Low Countries from 1829 onwards, cf. page 65. Born in Ghent in the new French republic in 1796 he managed to contribute to meteorology, astronomy, mathematics, statistics, demography, sociology, criminology and history of science before he died in 1874. He certainly did not invent the census – several full-fledged censuses were taken earlier, for instance in Denmark. However, Quetelet made the census into a comprehensive international undertaking through his work to spread a more standardized enumeration methodology at statistical conferences, which he presided over from the 1850s onwards. Many enumerations taken before Quetelet cannot meet the strict demands of the definition above and we call them pre-censuses or census-like materials. Most censuses taken with his Belgian 1829 census as the source of reference meet the requirements of the definition. Thus, we can use his census recommendations as a measuring stick for census quality in different periods and places.

The modern Quetelet-style census is rooted in several historical developments, pinpointing different rationales behind census taking. First there was the putting together of all kinds of lists for the dual purposes of taxation and soldier conscription, often rosters of some partial population segments with not much more information than people’s names and addresses, in a tradition several thousand years old as can be seen from, for instance, the Bible. Another root is the mercantilist policy of the 18th century, which argued that the size of a nation’s population was the basis for its wealth and thus crucial to overview. This especially led to early enumerations in the colonies such as in North America, where the colonizers sometimes feared that the local settlements might die out. A further rationale was the census ordered in the US Constitution from 1790 for political reasons, in order to base democratic representation on population size in different districts.

On a more theoretical level, we can relate the modern population census to two victorious developments in the history of ideas, ideological changes with wide-reaching practical consequences for many aspects of human civilization. One is the predominance of science as a general model, including for the social sciences from the 18th century, by some denoted as scientism (Olson, 1993). Society should, analogous to the study of an organism, be taken apart, each part studied carefully and then an overview of how the parts work together should be presented. In the case of the census, each individual’s data should be noted on the census form, and based on this an overall statistical presentation of society be constructed. During the 19th century, the complementary ideological strengthening of nationalism helped the development of the census, pointing to nations as the ultimate units to be overviewed by population censuses. In the previous century it was rather mercantilism motivating census taking in order to monitor population growth as part of the effort to strengthen the country. Proto-nationalism played into this – with royalty and religion as pre-national factors which people could identify with (Hobsbawm, 1992).

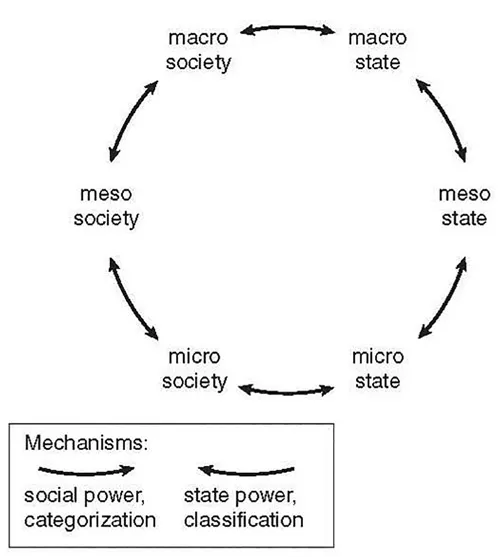

The historiography of the census has been written from the viewpoint of different agents who contributed to the contents of census forms, census instructions, categorization, encoding and the aggregating of census statistics. One tradition has highlighted the influence of the state, stressing how the authorities can use censuses and categories as instruments for pigeonholing the population according to the state’s preconceived ideas and notions (Desrosières, 1998; Curtis, 2001). An alternative interpretation is more attentive to the influence of social actors, both as representatives of diverse organizations interacting with the state in the process of deciding the contents of future censuses, and because it was necessary to base census taking on categories understood and accepted by common people when asking them to fill in the forms (Emigh et al., 2015a; Emigh et al., 2015b). As we shall see, the potential for different ways of describing relatively simple categories in the census is enormous. With self-enumeration in the nominative 1881 census for Britain there are two million different text strings in the occupation fields! The model by Emigh et al. presented in Figure 1.1 attempts to explain this variation by stressing the influence of the people over census categories by organizations on the national level (macro), political leaders on the regional level (meso) and the respondents on the local level (micro). The state’s census takers on different levels must negotiate the contents of the enumerations with the social power of the people and their representatives in a dialectical process. The present book will in addition highlight the influence of the statisticians meeting regularly in congresses and other international venues and organizations from the 1850s onwards, seeking to standardize census contents and methodology across nations, although often failing to reach concrete agreements.

Figure 1.1 Interactive model of information gathering (Emigh, Riley et al., 2015a: 39)

No single book can provide an overview of all the censuses taken around the world, with all the multitude of details with respect to methodology and contents. No single scholar can utilize more than a fraction of the national and international literature with results from the thousands of censuses taken during the last couple of centuries. Much of it is contained in bibliographies and more is kept by the libraries of national statistical bureaus worldwide (University of Texas, 1965–68; Goyer, 1980; Goyer and Domschke, 1983). Much of this variation has fortunately been captured systematically in the three Handbooks of National Population Censuses compiled in 1983, 1986 and 1992 by Doreen S. Goyer, Eliane Domschke and Gera E. Draaijer. They have organized these volumes by continent and country and mainly list details about the more recent censuses, while dealing more cursorily with material originating before the 20th century. Further information about specific censuses, especially the most recent ones, can be found on many Internet sites (Wilson, 2015). The aim of the present book is rather to illuminate the long-term development of the population censuses as an international phenomenon where national differences remain in spite of international efforts to standardize them. Readers who seek information about a specific census in a specific country should browse one of the three handbooks. While these build on and primarily describe the aggregate census results, however, the present book will focus more on the primary census manuscripts.

While the census handbooks described above are organized country wise, the overall organization of this book is chronological rather than by country. This is precisely because the overarching aim here is not to describe each census in all detail, but rather to analyze the national and international development of census taking as processes of informal and formal cooperation between bureaucracies responsible for national enumerations. Because there were differences in the development of the censuses between nations, however, within each chapter the main organization is by country. A central question deals with the virtual standard for census taking launched by Adolphe Quetelet in Belgium in the 1840s. We shall ask to what degree earlier censuses met his requirements and to what extent the international statistical conferences made the participating countries standardize their censuses rather than follow traditional national rules for census taking or specific needs that had to be met by regional adaptation?

In addition, other themes recur throughout the book. One is the need of the census-taking authorities to balance the need for information against the cost of the enumerations. Both the scope of the census with respect to what part of the population to include, what questions to ask, choice of methodology, what competence level of personnel to employ and whether to procure technology that is more efficient, influence the quality of the census and also the expenses. The balance of power between the central authorities and the regional and local nexus of influence decided whether the state could manage to take a census. We see this most easily when contrasting some countries’ lack of enumerations at home and the active census taking in their colonies. Periods of war and unrest also disrupted this balance of power: under such circumstances, it is seldom feasible to carry out censuses. After wars and revolutions, however, new regimes intensified their efforts to take stock of the country’s population, most notably in the US, France and the Soviet Union.

Contents of the chapters

After this introduction, the book starts out with the pre-censuses source materials, which – to the extent that we know their scope and methodology – did not contain the whole population, but rather grown men expected to pay taxes or be conscripted as soldiers. This period of partial enumerations stretches from Babylon and the biblical censuses thousands of years BC to the end of the 18th century. From 1801, however, censuses were taken which were modern enough that we must discuss whether they met so many of Quetelet’s recommendations that we have to include them among population censuses proper. Thus, the 18th and first half of the 19th century was a transitional phase in census taking. The first pre-censuses administered by France, Britain and Denmark were taken in their colonies rather than in their homelands. An important question is whether the marginal existence of the dominions due to wars and natural disasters necessitated this, or whether the reason rather was that the colonial populations could not muster the resistance established by regional leaders in the homelands to stop census taking.

The second chapter investigates how the number of censuses multiplied from the late 1700s, and why this change happened during the revolutionary period in the late 18th century. Was it due to the removal of influence from the regional gentry who had opposed previous census taking, was it because the population could no longer resist “taxati...