The systems and equipment used in nuclear power plants are sophisticated, complex, difficult to maintain and costly. They must operate for long periods of time without a serious failure and must have a very long total life. Furthermore, the physical environment in nuclear plants is very severe and can have a serious detrimental effect on the equipment, especially on complex mechanical and electronic components. High temperatures, vibration, high humidity, corrosive fluids and gases all take a toll on electromechanical devices and electronic components. Also, a large portion of the equipment must operate remotely after startup and depend on human operators for operation and control. These and other application factors make it essential that special attention be applied during acquisition to ensure the actual operational reliability of the equipment used in nuclear power plants.

There is great incentive for achieving high reliability. First, and most importantly, the safety requirements of nuclear power plants are of paramount concern. Also, the very large cost of designing and constructing a nuclear power plant and the large cost associated with plant downtime (as much as $800000 per day in power replacement cost alone) provide a strong economic incentive toward designing-in, or improving equipment reliability. Furthermore, failures are highly visible and, if they are serious enough or occur frequently, they could affect the whole industry. For these reasons, the nuclear industry is making a heavy commitment to safety with special emphasis on the acquisition and operation of ‘high reliability’ systems and equipment. This involves implementing well-conceived reliability programs and the application of disciplined analysis methods and controls. In addition to the design of highly reliable equipment, the industry is applying a great amount of system redundancy and functional diversity within each facility to help ensure the safety of the overall operating plant.

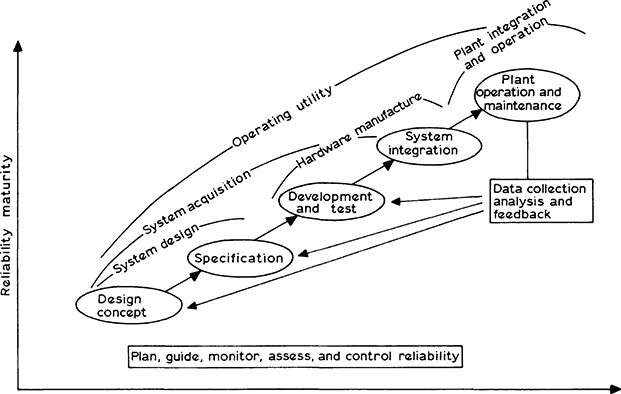

The achievement of reliable systems requires careful planning followed by a well-executed program with engineering tasks that start when the design concept emerges and continue through development, plant construction and operation. Reliability must be treated as a basic design parameter on a par with performance and cost. It requires establishing adequate requirements, providing necessary resources (i.e. skills, tasks, etc.) for its realization and exercising authority to assure that the consequences in reliability are made part of each decision during the acquisition process. Reliability maturity for a new system is only reached through the application of systematic, well-planned and controlled, life cycle tasks performed by the system designer, the hardware manufacturer and the procuring operating utility (see Fig. 1.1). A brief summary of the specific tasks for each life cycle phase is given below:

These tasks must be an integral part of the overall acquisition-operational process during which the required level of reliability is first planned by the utility, specified by the system designer and then implemented into the equipment by the manufacturer. In structuring a reliability program, prime consideration must be given bo ensuring safety by selecting and specifying the necessary program tasks to be applied individually or in sequence with other tasks. These tasks, as they are planned and applied during an equipment life cycle, will help in meeting requirements (both quantitative and qualitative) for design integrity and maintaining component availability. They also support the prevention of manufacturing and installation errors, contribute to the development of proper operating and maintenance procedures, and aid in controlling system configuration, in providing feedback from operating experience and in conducting personnel training. It should be noted that, although an effective reliability program includes tasks applicable to each phase of a system life cycle, current emphasis, because of the present state of the nuclear industry, is placed on the adequacy of the operational and maintenance procedures, on identifying and mitigating the aging mechanisms of safety related components, on recording data and analyzing failures, on implementing configuration management controls and on performing other tasks during plant operation.

1.1 Overview of the Nuclear Industry

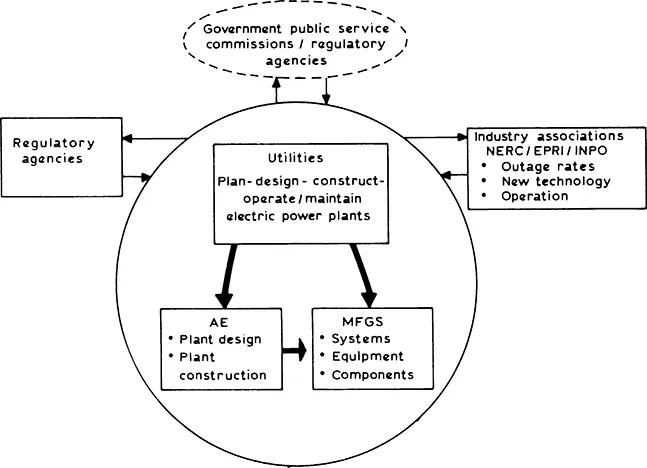

The role and relationships of the major organizational elements involved in the acquisition, operation and regulation of systems used in US nuclear power plants is shown in Fig. 1.2. The figure shows that the US nuclear power industry consists of the utilities, architect-engineering (A-E) firms, manufacturers and suppliers (including nuclear steam supply system (NSSS) vendors), and the Department of Energy/Department of Defense (DOE/DoD) and trade associations (National Electric Research Council (NERC), Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), Institute of Nuclear Power Operations (INPO) and Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE)). Each in various ways supports the overall objective of the industry to supply safe and reliable electric power to the public at the lowest cost while complying with regulatory agencies, including the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC).

Fig. 1.2 Nuclear power generating industry (conceptual).

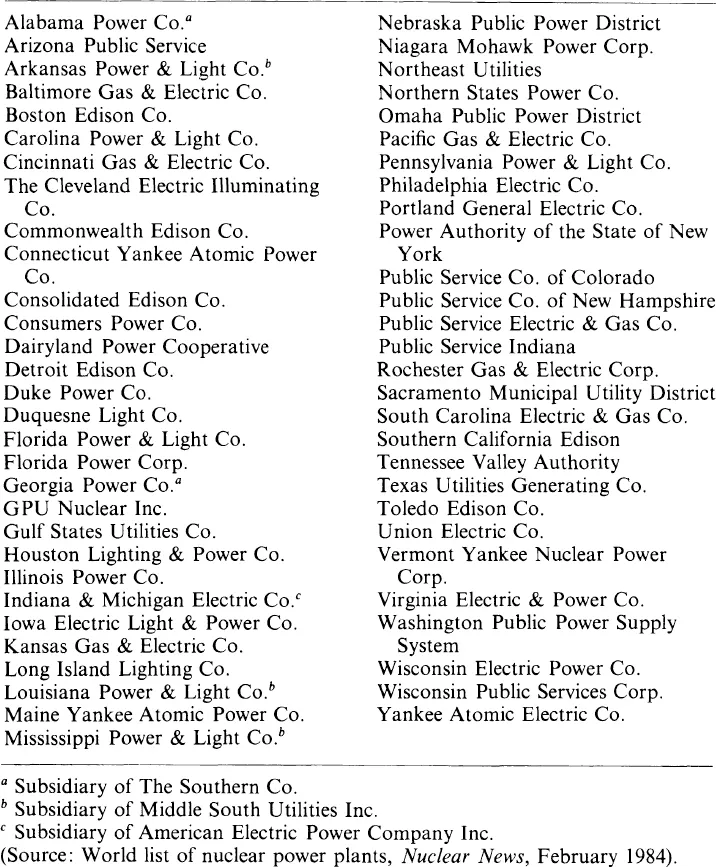

As of December 31, 1981, there were 76 operating nuclear power plants in the United States with an additional 90 under construction or on order. These nuclear power plants were, are, or will be, planned, designed, constructed, operated and maintained by electric utilities under license from the NRC. The 58 electric utilities with one or more nuclear power plants operable, under construction, or on order, as of December 31, 1983, are listed in Table 1.1.

The nuclear reactors for the power plants are supplied by NSSS vendors. There are currently five active NSSS vendors in the US—Westinghouse Electric Corp., Combustion Engineering, Babcock & Wilcox Co., General Electric Co. and General Atomic Co. The first three of these vendors supply pressurized water reactors (PWRs); General Electric supplies boiling water reactors (BWRs); General Atomic supplies high temperature gas-cooled reactors (HTGRs).

Table 1.1 US Electric Utilities with Nuclear Power Plants Operable, Under Construction, or on Order, as of December 31, 1983

In most cases, the utilities are assisted in the design and construction of the plants by architect-engineer (A-E) firms. For the plants operable, under construction, or on order as of December 31, 1981, there were 10 different A–E firms involved: Bechtel Power Corp., Black & Veatch Consulting Engineers, Burns & Roe Inc., Ebasco Services Inc., Fluor Power Services Inc., Gibbs & Hill Inc., Gilbert Associates Inc., Sargent & Lundy Engineers, Stone & Webster Engineering Corp. and United Engineers and Constructors Inc.

The system, equipment, and components for the plants come from any of many thousands of manufacturers, assemblers and suppliers. These suppliers may interact in their work with the utilities, the NSSS vendors, the A–E firms, or any combination of them.

The US nuclear industry is supported technically by several organizations. The DOE sponsors research and development, including the construction and operation of demonstration plants, in the nuclear power area. The electric power industry itself has formed the EPRI to carry out research and development in all areas of the industry; a portion in the nuclear power field. Following the accident at the Three Mile Island, Unit 2, Nuclear Power Plant, the US nuclear industry formed two additional supporting technical organizations: the Nuclear Safety Analysis Center (NSAC) at EPRI to improve nuclear plant safety and INPO to improve nuclear plant operations.

The Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) began operation in 1973 under the voluntary sponsorship of the US electric utility industry—private, public, and cooperative—for the purpose of expanding electric energy research and development. Its objective is to advance capability in electric power generation, delivery, and use in the public interest, with special regard for efficiency, reliability, economy, and environmental considerations. NSAC, which is part of EPRI, was established in April 1979 after the TMI incident; its efforts are focused on (1) the analysis of current safety concerns, (2) evaluation of the work being done to address these concerns, and (3) identification and implementation of any additional work that is needed to help improve nuclear plant safety. NSAC also develops position papers on those issues that can be used by utilities in regulatory matters. NSAC concentrates on events of potentially serious consequences but relatively low probability which have a hardware and procedural orientation.

A specific area of NSAC interest is that of developing accelerated equipment aging techniques. A major goal in the evaluation of safety-related equipment is the prevention of failures due to common causes in redundant safety systems. Since equipment aging is a potential common-mode failure mechanism, it is essential to demonstrate, during the design and manufacture of safety-related electrical equipment, that the equipment can function under design-basis condition—not only in an ‘as new’ condition but also after the degrading effects of in-service aging have occurred. NSAC efforts include reviewing equipment aging theory and assessing qualitatively the vulnerability of equipment with respect to aging, particularly with respect to common-mode failures. This organization has also looked at the possibility of artificially aging equipment based on the Arrhenius relationship in order to demonstrate that aged equipment can function after an accident. NSAC activities are driven by IEEE STD-323-1974 (Qualifying Class IE Equipment of Nuclear Power Generating Stations). This standard calls for accelerated aging in a time-correlated fashion such that a ‘qualified life’ may be demonstrated.

While EPRI is the R&D arm of the utilities, the Institute of Nuclear Power Operations (INPO) is their operational arm geared to establish industry-approved standards for the operation of nuclear power plants and to ensure that the utilities meet those standards. It is, in effect, a self-imposed policeman of the nuclear power industry; all of the utilities operating nuclear power plants in the US belong and provide financial support, to INPO. INPO became operational in December 1979. It was created by the utilities in rapid response to the TMI accident in affirmation of the nuclear industry’s commitment to safety.

INPO’s primary duties are evaluating the management and operation of US nuclear plants and recommending improvements. The goal is to evaluate all US nuclear plants at least once a year. After each evaluation, INPO drafts a preliminary report which it sends to the utility for its review and response. INPO staff members then meet with utility management to agree on actions to be taken in response to INPO’s recommendations, and target dates are set for each item. These are included in the final report sent to the utility. The utility is asked to inform INPO when the targets are met. INPO continually informs the industry of ‘best practices’ that it has found as a result of its activities.

Other work performed by INPO includes studying human factors improvements and developing human reliability data for probabilistic risk assessment. They also operate a computer communications network called NOTEPAD. Utilities that join the network can talk back and forth, querying one another about equipment and practices and receiving information from INPO. Licensee event reports (LERs) and other unusual occurrences reported by utilities are reviewed by INPO as a first step in their ‘Significant Event Evaluation and Information Network’ (SEE-IN) program. The SEE-IN program was directed primarily at screening and analysis of LERs. As the SEE-IN program developed and matured, it became increasingly apparent that a comprehensive, effective experience feedback program must be based on screening and analysis of significant plant events and equipment, and component failures, and on the identification and reliability assessment of key equipment in critical accident sequences. Ready access to an effective component-reliability database is a vital part of such a program.

In light of the need for a component reliability database to support INPO activities. INPO, in January 1982, assumed the management, technical direction, and funding of the ‘Nuclear Plant Reliability Data System’ (NPRDS). NPRDS collects and disseminates operating reliability statistics for safety-related components and systems in commercially operated US nuclear power plants. Information is collected on 29 major categories of components of mechanical and electromechanical designs. The information may be used for reliability and maintainability prediction and assessment, and for design improvement programs. Participants in NPRDS are provided with access to (1) complete engineering data on components and system, (2) unit and system operating hours, (3) statistics on reliability performance of equipment, and (4) complete description of component failure, including mode, type, cause, effect, and detection.

In addition to the NPRDS data function, the National Electric Research Council (NERC) is responsible for the operation of the ‘Generating Availability Data System’ (G...