1.1. Introduction

The purpose of this report is to provide the reader with a detailed background of the fundamentals involved in the bioremediation of contaminated surface soils, subsurface materials, and ground water. A number of bioremediation technologies are discussed along with the biological processes driving those technologies. The application and performance of these technologies are also presented. These discussions include in-situ remediation systems, air sparging and bioventing, use of electron acceptors alternate to oxygen, natural bioremediation, and the introduction of organisms into the subsurface. The contaminants of major focus in this report are petroleum hydrocarbons and chlorinated solvents.

Location of the contamination in the subsurface is critical to the implementation and success of in-situ bioremediation. Also important to success is the chemical nature and physical properties of the contaminant(s) and their interactions with geological materials.

In the unsaturated zone, contamination may exist in four phases (Huling and Weaver, 1991): (1) air phase - vapor in the pore spaces; (2) adsorbed phase - sorbed to subsurface solids; (3) aqueous phase - dissolved in water; and (4) liquid phase -nonaqueous phase liquids (NAPLs). Contamination in saturated material can exist as residual saturation sorbed to the aquifer solids, dissolved in the water, or as a NAPL. Contaminant transport occurs in the vapor, aqueous, and NAPL phases. The interactions between the physical properties of the contaminant influencing transport (density, vapor pressure, viscosity, and hydrophobicity) and those of the subsurface environment (geology, aquifer mineralogy and organic matter, and hydrology) determine the nature and extent of transport.

NAPL existing as a continuous immiscible phase has the potential to be mobile, resulting in widespread contamination. Residual saturation is the portion of the bulk liquid retained by capillary forces in the pores of the subsurface material; the NAPL is no longer a continuous phase but exists as isolated, residual globules. Residual phase saturation will act as a continuous source of contamination in either saturated or unsaturated materials due to dissolution into infiltrating water or ground water, or volatilization into pore spaces.

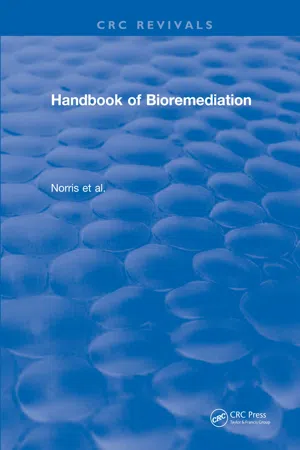

Liquids less dense than water, such as petroleum hydrocarbons, are termed light nonaqueous phase liquids (LNAPLs). LNAPLs will migrate vertically until residual saturation depletes the liquid or until the capillary fringe is reached (Figure 1.1). Some spreading of the bulk liquid will occur until the head from the infiltrating liquid is sufficient to penetrate to the water table. The hydrocarbons will spread laterally and float on the surface of the water table, forming a mound that becomes compressed into a spreading lens due to upward pressure of the water (Hinchee and Reisinger, 1987). Fluctuations of the water table due to seasonal variations, pumping, or recharge can result in movement of bulk liquid further into the subsurface with significant residual contamination present beneath the water table. The more soluble constituents will dissolve from the bulk liquid into the water and will be transported with the migrating ground water.

Figure 1.1. Distribution of petroleum hydrocarbons in the subsurface.

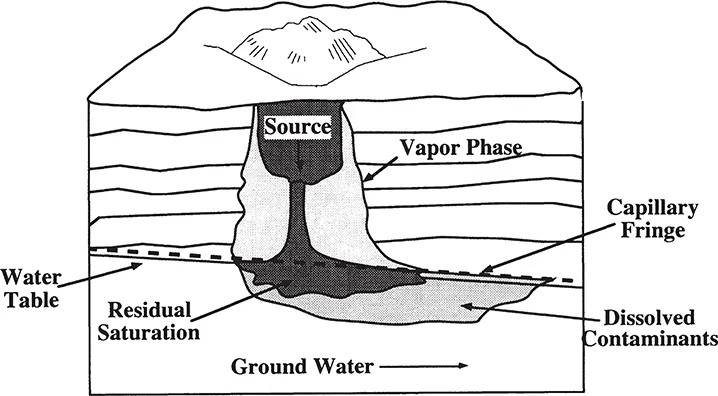

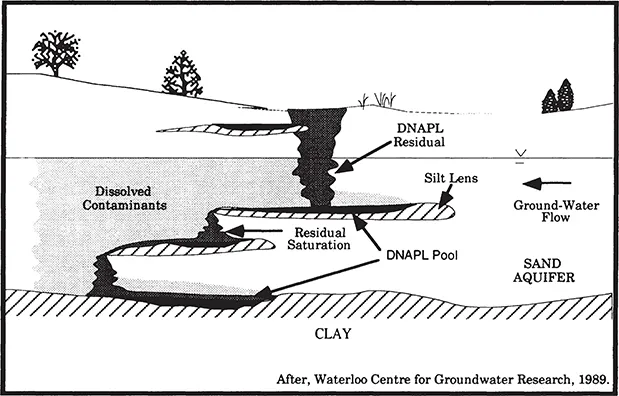

Vertical migration of dense nonaqueous phase liquids (DNAPLs) will continue through soils and unsaturated materials under the forces of gravity and capillary attraction until the capillary fringe or a zone of lower permeability is reached. The bulk liquid spreads until sufficient head is reached for penetration into the capillary fringe to the water table. Because the density of chlorinated solvents is greater than that of water, DNAPLs will continue to sink within the aquifer until an impermeable layer is reached (Figure 1.2). The chlorinated solvents will then collect in pools or pond in depressions on top of the impermeable layer. DNAPL contamination in heterogeneous subsurface environments (Figure 1.3) is difficult to both identify and remediate.

Bioremediation of ground waters, aquifer solids, and unsaturated subsurface materials is widely practiced for contaminants derived from petroleum products. Currently, the most important techniques for bioremediating petroleum-derived contaminants are based on enhancement of indigenous microorganisms by delivery of an appropriate electron acceptor plus nutrients to the subsurface. These techniques are in-situ bioremediation, bioventing, and air sparging; natural bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons is also discussed. This paper presents sections devoted to each of the above-mentioned techniques authored by experts actively engaged in bioremediation and research. The sections are: Section 2, In-situ Bioremediation of Soils and Ground Water Contaminated With Petroleum Hydrocarbons; Section 3, Bioventing of Petroleum Hydrocarbons; Section 4, Treatment of Petroleum Hydrocarbons in Ground Water By Air Sparging; Section 7, In-situ Bioremediation Technologies for Petroleum-Derived Hydrocarbons Based on Alternate Electron Acceptors (other than molecular oxygen); and Section 9, Natural Bioremediation of Hydrocarbon-Contaminated Ground Water.

Figure 1.2. Migration of DNAPL through the vadose zone to an impermeable boundary in relatively homogenous subsurface materials (Huling and Weaver, 1991).

Figure 1.3. Perched and deep DNAPL reservoirs from migration through heterogeneous subsurface materials (Huling and Weaver, 1991).

Chlorinated solvents are more difficult to bioremediate than petroleum hydrocarbons, and bioremediation efforts are still in the research and development stage. Biological processes for most chlorinated compounds, whether aerobic or anaerobic, require the presence of a primary substrate for cometabolism. Both enhanced and natural bioremediation of chlorinated compounds are widely investigated in laboratory, pilot-scale, and field-scale studies. Results of these efforts are presented in the following sections: Section 5, Ground-water Treatment for Chlorinated Solvents; Section 6, Bioventing of Chlorinated Solvents for Ground-water Cleanup through Bioremediation; Section 8, Bioremediation of Chlorinated Solvents Using Alternate Electron Acceptors; and Section 10, Natural Bioremediation of Chlorinated Solvents.

The introduction of microorganisms to the subsurface for bioremediation purposes is discussed in Section 11, Introduced Organisms for Subsurface Bioremediation. Although not considered a successful technique at this time due to concerns about survivability of introduced microorganisms, this method may someday be useful at sites sterilized by contamination.

Discussed in each section are basic biological and nonbiological processes affecting the fate of the compounds of interest, documented field experience, performance, repositories of expertise, primary knowledge gaps and research opportunities favorable and unfavorable site conditions, regulatory acceptance, special requirements for site characterization, and problems encountered with the technology. Although the focus of this paper is bioremediation, remediation of most sites will require use of other technologies not discussed, such as pump and treat, soil washing, etc. The place ofbioremediation in the cleanup of hazardous waste sites is still evolving, and evaluation of its effectiveness is under investigation by regulators, researchers, and remediation firms.

Hinchee, R. E., and H.J. Reisinger. 1987. A practical application of multiphase transport theory to ground water contamination problems. Ground Water Monitoring Review. 7(1):84–92.

Huling, S. G., and J.W. Weaver. 1991. Dense Nonaqueous Phase Liquids. Ground Water Issue Paper. EPA/540/4-91-002. Robert S. Kerr Environmental Research Laboratory. Ada, Oklahoma.