![]()

1 Further education into the 1980s

In the first edition of this book, we began by describing the phenomenal post-war growth in the further education sector in England and Wales by which the number of students more than doubled from 1,595,000 in 1946 to just over 4,000,000 in 1975 and the number of full-time teaching staff increased even more dramatically during that period from under 5,000 to over 76,000. In the last few years, the situation has remained relatively static, student numbers having declined slightly to 3,511,000 in 1980 and teachers numbering about 80,000 in that year. During the past twelve years, from 1970 until the time of writing, 1982, major changes have occurred throughout further education, as indeed in the country at large. At the beginning of the 1970s, there was still optimism and the expectancy of the continued expansion which had marked the previous decade; today we are all too grimly aware of the retrenchment and turbulence which are affecting most sectors of our educational system. Looking back over the period, we can see that two main factors were responsible for this radically changed position: the economic recession resulting in large part from the oil crisis following the 1973 Middle East war and the sharply declining birth rate of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The first years of the 1970s were marked by a public debate on the nature and content of teacher education and training, a debate which had rumbled on for many years but which came to a head at this time. Public concern led to the setting up of the James Committee, which issued its Report, Teacher Education and Training, in January 1972. Although the Report proposed no major institutional changes in the colleges of education sector, it did recommend that the colleges themselves should cease to be monotechnics providing only courses in teacher-training and should diversify their provision in the form of a two-year course of general education to be known as the Diploma of Higher Education (Dip.HE).

In December of the same year, the Conservative government of the day issued its White Paper, Education: A Framework for Expansion, which, as its title indicates, still envisaged a period of continued growth, especially in higher education. Accordingly, it recommended that student places in higher education should be increased from under 500,000 in 1972 to 750,000 in 1981, the places to be shared equally between the universities and the further education sector. In other words, the public sector colleges should accommodate 375,000students by 1981. This was to be accomplished partly by merging the great majority of the colleges of education, hitherto a separate sector of higher education, with polytechnics and other further education colleges. The White Paper, recognizing that there was some decline in the birth rate and that this would require a cut-back in the output of trained teachers, announced that the number of teacher-training places in the public sector colleges would be reduced from a maximum of 114,000 in 1972 to between 75,000 and 85,000 initial and in-service places by 1981. Finally, it strongly advocated the introduction of the Dip.HE as recommended by the James Report.

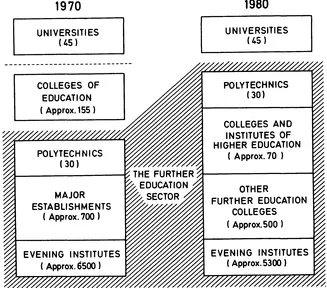

In the following March, the DES issued Circular 7/73, The Development of Higher Education in the Non-University Sector, asking local authorities and voluntary bodies to put forward detailed plans for the reorganization of the colleges of education which for the most part would be expected to move into the public sector. Clearly, at that time it was not envisaged that very drastic surgery would be required as the planned increase in student numbers would more than compensate for the reduction in teacher-training places. However, as the full impact of the steep decline in the birth rate, 832,000 live births in 1967 to just over 600,000 in 1975, began belatedly to be recognized by the DES, so it felt it necessary successively to reduce the number of teacher-training places in the colleges. The 'final' target figures, announced at the end of 1977, were 45,000 places by 1981, including some 9,000 for in-service courses for practising teachers. The fall-out from these decisions had far-reaching effects: the college of education sector disappeared; a number of colleges of education closed altogether; the merger of the remaining colleges with further education colleges created a new group of institutions known generally as Colleges or Institutes of Higher Education; and the further education sector acquired a substantial stake in teacher training, albeit considerably smaller than that envisaged in the 1972 White Paper. As a result, the institutional structure of further education changed substantially (Figure 1.1).

Closely linked with these developments was the growth of the Diploma of Higher Education. From the introduction of the first two courses in September 1974, student numbers have gradually increased to about 8,500 in 1980 on some 65 courses. However, these numbers are very tiny when compared to those of students on degree courses in further education who number more than 123,000 and, in any case, many of the Dip.HE programmes are, in effect, the first two years of an integrated degree course. It is therefore still too early to forecast the extent to which the Dip.HE will develop.

Figure 1.1 The changing pattern of further education, 1970 to 1980

The growth of higher education in the further education sector, together with the economic recession, inevitably focused attention on the financial management of the polytechnics and colleges of higher education. Understandably, they compare themselves with the universities and envy them their powers of self-validation and financial self-management, albeit within increasingly restricted budgetary limits. By contrast, the public sector institutions of higher education are constrained by the necessity of advanced course approval through the Regional Advisory Councils and the Department of Education and Science and validation through the Council for National Academic Awards, and by complex financial procedures exercised by the parent local education authorities and through the 'pool' (see p. 95). These matters received a public airing in the latter part of the 1970s and culminated in the 1978 Oakes Report, The Management of Higher Education in the Maintained Sector. The Oakes Report recommended the establishment of a national body for England to oversee the development of maintained higher education, a recommendation that was taken up by the Labour government which decided to press for the establishment of two national bodies, to be known as Advanced Further Education Councils (AFECs), one for England and one for Wales. This proposition was incorporated in an Education Bill which, by Spring 1979, had reached the Committee stage of the House of Commons when the general election intervened.

Having won the election, the Conservative government dropped the Education Bill and instead, during the past three years, first 'capped the pool' by determining that an annual finite amount of money should be made available for advanced courses, and then more recently created two bodies, the National Advisory Body for Local Authority Higher Education for England (NAB), and the Welsh Advisory Body for Local Authority Higher Education (WAB). The ways in which these bodies are likely to operate and their probable effects on advanced further education are discussed in detail in Chapters 5 and 7 respectively.

The institutional character of advanced further education looks set for further upheaval during the next few years. The effective reduction in the total sums of money made available by the government for advanced further education, together with the latest cuts in teacher-training places in public sector higher education, announced by the Secretary of State in July 1982, mean that NAB, and WAB are being faced with the unpleasant task of having to advise the government on the closure of departments and probably institutions, especially those which are largely concerned with initial teacher training.

The 1970s also witnessed far-reaching changes in the field of industrial training. The structure created by the Industrial Training Act of 1964, based upon the creation of industrial training boards, was coming under increasing criticism by the beginning of the decade on the grounds that the boards had had only limited success in increasing the quantity and improving the quality of training. Consequently, the government conducted a review of their work resulting in the publication in 1972 of a consultative document, 'Training for the Future'. It recommended the establishment of a National Training Agency to co-ordinate the work of the industrial training boards and to develop a national training advisory service, and it adumbrated the possibility of creating a general council on manpower services. These recommendations soon bore fruit with the passing in 1973 of the Employment and Training Act which declared the government's intention of establishing a Manpower Services Commission (MSC) under the aegis of the Department of Employment. The MSC would have as its main responsibility the promotion of more and better industrial training and for this purpose two executive bodies would be created, to be known as the Training Services Agency (TSA) and the Employment Services Agency (ESA). The government moved rapidly towards these objectives and the MSC was established in January 1974 and the TSA and the ESA in April 1974. In May 1975, the TSA (renamed the Training Services Division of the MSC in April 1978) issued a discussion document, Vocational Preparation of Young People, underlining the serious deficiencies in the existing provision and suggesting appropriate action. This, in turn, led to a joint initiative by the TSA and the Department of Education and Science, namely the establishment of a limited number of schemes of Unified Vocational Preparation (UVP) which cater for youngsters in employment, but not normally in receipt of education and training. The numbers of trainees on these programmes have grown steadily since their inception in 1977 and in 1980-81 they numbered 4,500. It is intended that these numbers will be greatly increased as part of the more far-reaching Youth Training Scheme (YTS).

The massive growth in youth unemployment which has been so distressing a feature in recent years led the government, through the MSC, to bring into being the Youth Opportunities Programme (YOP), operated by the Special Programmes Division (SPD), a branch of the MSC created specifically for this purpose. Set up in April 1978 to provide a comprehensive national scheme for unemployed school-leavers and stemming from the Holland Report, Young People and Work, published in May 1977, YOP is essentially an endeavour to prepare young people for work by means of work preparation and work experience schemes. It has been of great significance for the colleges in that it has introduced to further education a group of young people for whom they have scarcely catered before. This has thrust upon teachers in the colleges a considerable challenge, namely that of working out the most suitable provision for a group of youngsters many of whom have few or no qualifications and who in the course of their schooling were apathetic or even hostile towards education. The effect of this 'new further education' upon the colleges will be greatly increased when the Youth Training Scheme comes into effect in September 1983. Essentially, a year's full-time programme of work experience and associated further education, YTS may bring into the non-advanced sector of further education the equivalent of 80,000 full-time students. As this will occur at a time when the numbers of apprentices on 'traditional' part-time day and block release courses are steeply decreasing, the character of the vocational provision made by the further education colleges will increasingly suffer a sea change.

Another side effect of the decline of the national economy and the increasing difficulty which school-leavers face in finding jobs has been that a higher proportion of them are enrolling on full-time courses in the colleges. These are mainly those leading to GCE awards, both at O and A levels, Technician and Business Education Council Certificates and Diplomas and City and Guilds awards. Many of these students could have remained at school to continue their GCE studies; instead, for a variety of reasons, they have opted for the further education college. In some areas of the country, however, all provision for the sixteen to nineteen age group is made in one institution, known as the tertiary college, which we discuss in Chapter 3. As the effects of the sharp decline in the birth rate in the late 1960s and the first half of the 1970s begin to work their way through the education system, so it will become increasingly necessary to coordinate post-16 provision, presently made in school and further education colleges. In such circumstances local education authorities are increasingly turning to the tertiary college as an attractive solution to their problem.

Another major area of further education which came under the microscope of public opinion in the late 1960s was technician education. The Haslegrave Committee issued its Report on Technician Courses and Examinations in 1969, advocating the introduction of a unified pattern of courses of technical education for technicians in industry and in the field of business and office studies. The Report recommended the establishment of two new councils, the Technician Education Council (TEC) and the Business Education Council (BEC), to devise and approve an entirely new pattern of courses spanning both advanced and non-advanced further education. Although these recommendations were accepted by the government, there was a long delay before the new councils were created, so that it was not until March 1973 that TEC came into existence and May 1974 before BEC appeared upon the scene. Since then, however, as a result of the activities of the two councils, a completely new pattern of education and training for middle-level manpower has emerged embracing not only education for technicians in industry and business but also some aspects of art and design education.

As a result of these and other developments, the number and variety of courses in the further education colleges available to the sixteen to nineteen age group have in recent years become even more complex. In the last few years, the emphasis has been placed on the area of vocational preparation, as distinct from traditional vocational education which has been in decline, culminating in proposals put forward by the DES in May 1982 for the Certificate of Pre-Vocational Education. Courses leading to this award are due to start in 1984, both in schools and in colleges, and they are expected to enrol about 80,000 students a year. In the meantime, the City and Guilds has expanded its provision of its pre-vocational Foundation Courses and in 1981 introduced its Certificate in Vocational Preparation (General). It remains to be seen whether all three of these pre-vocational courses succeed in securely establishing themselves.

A belated and encouraging development in recent years has been the increase in teacher training and staff development for further education, partly stimulated by curriculum changes wrought by bodies such as TEC and BEC and the CNAA. The 1975 and 1978 Haycocks Reports on the training of full-time and part-time teachers of further education respectively have stimulated a most welcome increase in the provision of in-service teacher-training courses, especially in the form of two-year part-time courses for full-time teachers leading to Certificates in Education (FE). However, even today fewer than half the teaching staff in further education possess a teaching qualification recognized by the DES.

Wales, like England, has been subject to these changes but events there were given an added dimension both by the transfer to the Welsh Office of responsibility for all post-school education other than the university and also by the debate which preceded the referendum on devolution. Had the people of Wales voted in favour of devolution, it would have resulted in the creation of a Welsh Assembly with ultimate responsibility for all further education provision in Wales.

Finally, the past twelve years have witnessed an encouraging growth in research and curriculum development in further education. The number of research projects currently in operation is considerably larger than it was at the beginning of the 1970s. However, in terms of volume, it still lags far behind the amount of educational research sponsored by the university and school sectors. Curriculum development has been given a fillip by the work of such bodies as the Technician and Business Education Councils and the City and Guilds of London Institute, and by the need to cater for youngsters undertaking YOP and unified vocational preparation courses. The setting up, in January 1977, of the Further Education Curriculum Review and Development Unit (FEU) was a most welcome development and, in its first five years, it has already contributed greatly to much needed curriculum development in the further education colleges.

Thus, during the 1970s, the further education sector underwent a major transformation, including substantial changes in higher education within further education, like the creation of the colleges and institutes of higher education and the introduction of the Diploma of Higher Education. Major curricular developments took place in technician education as a result of the work of TEC and BEC; teaching training and staff development in further education increased and the growing problem of unemployment stimulated the provision by the MSC of industrial training and associated further education and highlighted the need properly to integrate education and training.

During the first two years of the 1980s the landscape of further education has changed still more. Within advanced further education, the sums of money available to the polytechnics and colleges of higher education have, in real terms, diminished substantially and, as we have seen, the numbers of initial teacher-training places have been reduced, resulting in the probable closure in the near future of departments and institutions. The 'capping' of the advanced further education pool and the creation of NAB and WAB have introduced a new, and more rigorous, form of financial management. In the non-advanced sector, the character of its provision is also undergoing a substantial change. The decline in our manufacturing industry has led to a proportional decline in apprenticeships and consequently in the traditional vocational courses which the colleges have provided for them. Increasingly, however, the slack has been taken up by 'new further education', the provision of programmes for unemployed youngsters through the Youth Opportunities Programme and shortly through its successor, the Youth Training Scheme. That the further education sector is proving able to accommodate these enormous changes, albeit under considerable stress, is a tribute to its flexibility and to what seems at times its almost infinite capacity for adjustment.

![]()

2 The administrative framework

The educational system of England and Wales is commonly described as a 'national system, locally administered', with the Department of Education and Science as a major ope...