eBook - ePub

Care Management and Community Care

Social Work Discretion and the Construction of Policy

- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Care Management and Community Care

Social Work Discretion and the Construction of Policy

About this book

This title was first published in 2000: Community care stands as an example of a complex policy, failing to be implemented as intended. Using research and studies of literature on community care, this text investigates the reasons behind the failure of this "flagship" policy, focusing on the part played by care managers, management and policy implementation approaches. It presents an exploration of social work discretion as a potential force for positive and dynamic implementation, as opposed to the usual analysis of professional discretion as a necessary evil. This potential is demonstrated through the analysis of an innovative research methodology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Care Management and Community Care by Mark Baldwin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Sociologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 General Introduction - Reflecting on the Process

This book is a record of research that has been both theoretical and empirical. It sets out to contemplate the limitations to policy implementation in an environment in which there is room for interpretation of policy through the use of professional discretion by frontline staff within implementing organisations. This has enabled me to make a study of the use of discretion, a subject which has been written about in largely negative terms in the critical literature. The illustrative example is the implementation of Community Care policy during the 1990s, with the empirical work consisting of an analysis of literature, including Local and Central Government documents and direct contact with people involved in the implementation process, primarily at the lower end of Local Government Social Services Department hierarchies (care managers and first line managers). I set out with an interest in knowing how it was that care managers (a key group of professionals in the implementation of Community Care policy) knew what they should do given the bewildering array of knowledge available to them to draw upon in their practice. There is, in what follows, a brief history of the development of Community Care as well as an analysis of the key texts that define the policy intentions of Central and Local Government for the prime tasks of assessment and care management. Empirical work has taken me to meet with care managers and their managers to ask them what informs their practice in carrying out these sophisticated roles, and an interpretation of these meetings is included in detail. Having discovered from this empirical work that not only do care managers find such explanation hard, but also that their practice was in many ways different from the intentions of policy makers, I was then interested in exploring why this should be. This led me on a further journey of exploration providing more information on which I could reflect and increase my understanding.

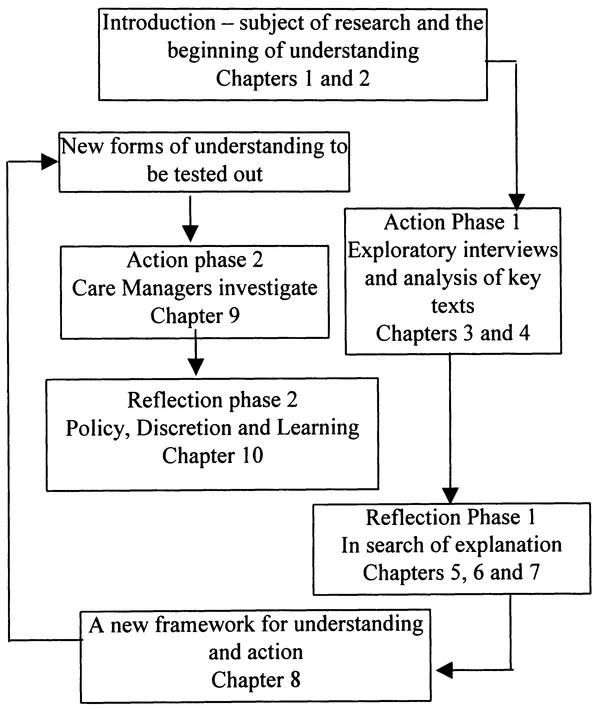

The book structure can be seen to follow these cycles of action and reflection as my learning and understanding has developed (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Structure of the Book

Chapter 1 starts with a general introduction, but also includes a section in which there is a reflection on the personal process of learning involved in this research journey. This justifies the process of action and reflection which is illustrated in figure 1 and provides the structure for the remainder of the book. Chapter 2 offers some contextualisation, taking the reader through some of the problems of policy implementation revealed within policy implementation theory. The chapter is an introduction to the illustrative policy area, and provides the reader with a history of recent developments in Community Care, and the current context in which care managers practice.

Chapter 3 takes the reader into the first period of action. It is an analysis of research interviews carried out with care managers and managers in two Local Authority Social Services Departments. Chapter 4 provides an analysis of some of the key texts which define Community Care. The research interviews demonstrated considerable confusion within the care management field, and the research exploration from that point has been an attempt to explain some of the problems that were encountered. If the interviews provided evidence that policy intentions are undermined by the actions of key implementers such as care managers, it was important to analyse why this should be. The analysis of key texts casts some light on the ambiguities within Community Care policy which add to our understanding of the implementation difficulties. The failure of these documents to provide a single comprehensive version of community care policy which speaks equally to all stakeholders leaves room for interpretation and discretionary behaviour which is likely to undermine intentions when they are based upon policy implementation as a rationalist exercise.

Chapter 5 takes the reader into a reflective phase in which theoretical material is used to address further the problems raised by the interview analyses. It provides a closer look at one key aspect of policy implementation theory, specifically that part that offers an explanation of the role played by front-line implementers. This takes us into the world of Michael Lipsky's Street Level Bureaucrats (Lipsky 1980) and the influence that they can have on policy implementation. Chapter 6 provides an analysis of public service management and the rise of managerialism in public policy during the 1980s and 1990s. The influence of managerialism has been considerable, during this period, and the way in which it has affected policy and practice development has the potential to explain some of the problems facing policy implementation. Chapter 7 puts the spotlight on social work theory. Most care managers are social workers, and it is important to explore what, in theory, might be the forms of knowledge that social workers are drawing upon to inform their practice. Chapter 8 is the last in this reflective phase and analyses 'new paradigm research' (Reason and Rowan 1981) methodology, which has more recently been defined as a 'participatory inquiry paradigm' (Heron and Reason 1997) in contrast to more traditional research within a positivist epistemology. This chapter also provides a link into the final section, reflecting upon knowledge within policy implementation, management, social work and research theory to construct an integrated epistemological framework to help address the main research questions.

Chapter 9 takes the book back into action mode. The coherent epistemological framework developed in the previous chapter is tested out in this one. It is an analysis of two co-operative inquiry research groups which the author was involved in over a six month period with two groups of social workers operating as care managers. These co-operative inquiry groups enabled me to test out the usefulness of experiential participative research methodology and other forms of knowledge to understand the complexities of policy implementation.

Chapter 10 is the final reflective section and provides conclusions in the form of present learning and future action in policy implementation, the use of professional discretion, and organisational structure and management. Some claims are made for the usefulness of participation and reflective practice as starting points for both the study and implementation of policy in a context of organisational learning. It is argued that participation and reflection are more useful than the rationalist and positivist approaches analysed earlier in the book.

How practice differs from policy intentions is of great interest to a number of people, and there is information within the book that covers that ground. It is not the prime focus, however, which is more on whether care managers have an influence on policy outcomes and why it happens in the ways discovered, and if it has to be like this. There is also a case made for a more effective methodology for investigating these questions. I have used a range of theoretical perspectives to help explain why this happens and to explore some of the implications for the future, both in terms of further research and future implementation practice. It is important to ask why it is of interest to know whether care managers can skew policy implementation through their discretionary behaviour. There is a view expressed that there is some inevitability that policy will be determined more through frontline workers' practice rather than from the top down. If that is the case then presumably frontline workers-care managers in our case-would want such influence to be positive and developmental, adding to the quality of service and advocating the values, knowledge and skills that they believe to be important and effective. Evidence of the unbridled and unreflective use of discretion suggests that, for a number of reasons, care managers do not have a controlling hand on the way in which their practice determines policy outcomes. More deliberate and considered use of discretion might, along with the introduction of other practices, actually make service delivery more effective from a number of perspectives. That is why it is important to explore whether care managers skew policy implementation, why and how this happens.

The whole book, though, is rooted firmly in the empirical work and most notably the two periods of fieldwork. The first involved a close look at the practice of care managers and the second, engagement in a process of practice development with two groups of practitioners. Both these forms of fieldwork-the snapshot and the process-tell us much about the whether, the how and the why, as well us being a useful evaluation of research methodology as it shifted from a traditional qualitative approach to a participative action orientation.

The book starts with the big questions. "What are the limitations to successful policy implementation?" and, more specifically, "are policy intentions undermined by frontline or "street level" implementers?" There is also a third question assuming that the answer to the second is "yes". The additional question is-"what better explanation is there for understanding the actions of street level implementers which might provide a model for more successful implementation?"

The problem that continually raises its head is that of rationalism. Whilst in no way wishing to undermine our status as rational beings who have to make sense of our lives in structured ways, I have struggled, in this journey of exploration, to understand why it is that rationalist forms of social action, based on positivist epistemology, hold such powerful sway in all the key areas of exploration-policy implementation, organisational and managerial structure, professional practice and research methodology. We need to explore if policy can be implemented through rationalist means, whether informed by policy implementation theory at the macro level, scientific managerialism at the mid point or traditional social work theory at the micro level. The problem is not so much that scientific rationalism is used to explain these areas of interest, but that its construction of a particular form of reality through the powerful deployment of discursive practices (Parker 1992) or persuasive rhetoric (Majone 1989; Soy land 1994), is largely unquestioned outside of academic reflexivity.

Positivism is the philosophical approach to epistemology that accepts a unified conceptualisation of reality describing what we all experience and can agree upon. Scientific rationality is the form of social action that involves uncovering, revealing or responding to the objective reality construed by positivist epistemology. Rationalism then creates practices and institutions which are based upon this objective reality. By ignoring the 'important problems' that positivism glosses over (Berger and Luckmann 1966; p. 210), rationalist social action is unable to take account of the ways in which any form of social action constructs, or legitimates, the realities which are more helpfully viewed as 'symbolic universes' (Berger and Luckmann 1966; p. 210). There is much support for this critique of positivism and scientific rationalist social action, notably within the field of social work theory and practice both implicitly and specifically, from a range of perspectives or viewpoints including reflective practice (Schon 1983, 1987; Laragy 1996; Fook 1996), feminism in social research (Gregg 1994), existentialism (Thompson 1995), post-modernism (Howe 1996) and critical reflexive approaches to the evaluation of practice (Shaw 1996).

It is my intention to investigate some of the problems created by these rationalist institutions because of my observation that policy is implemented by people through processes of interrelationship, within organisational structures. People, with their multitudinous and messy ways of making sense of everyday life, create these relationships and organisational structures in a far more fluid and relativist way than rationalism, as defined above, allows. The constructivist version of reality is built upon an uncertain and contingent epistemology. It requires an exploratory and flexible approach to learning. It has revealed to me, in my process of learning, the problems that the clarity and certainty of rationalism create. Assuming the reality is there to be found, it constricts the range of possibilities, failing to acknowledge that what is actually happening is a continual and fluid construction of social reality. Rationalism is not searching for truth but constructing it. The essentialist assumption, however, means that the search continues in unacknowledged, unreflexive and assumptive fashion. Rationalism is, therefore, linear in its process of making sense, and blinkered in its field of vision.

In this book I investigate rationalist approaches to policy implementation, organisational process, management, professional practice and research methodology, and deconstruct the powerful realities, or 'symbolic universes' that they have created within the focus of attention-Community Care implementation. I pose claims to new paradigms in the forms of knowledge that help us make sense of these areas. I am tackling, therefore, some of the 'important problems' ignored by positivist rationality in this area of investigation. The main problem is the use of discretion and the way that its use in policy implementation constructs a different version of policy to that intended by policy creators. Discretion by care managers can then be viewed as the social construction of one form of social reality for Community Care. Discretion is an activity which has been demonised as professionals out of control, requiring increasingly technocratic responses to regain authority by policy implementers higher up the implementation hierarchy. There is no reason, I wish to argue, why discretion should not be seen as a more constructive opportunity to implement policy such as Community Care, as a co-operative and participatory activity.

I started out on this enterprise as a solo traveller. In the latter stages, I realised that it was important to work alongside others making sense of the puzzling area of focus, to collaborate with a group of people who wrestle with the ambiguities and confusions of 'the swampy lowlands' (Schon 1987) of community care on a day-to-day basis. Ultimately we all have to make our own sense of what lies before us, and to act on that knowledge. My emerging belief that we create our real world in relationship with others has led me to realise that empirical work is most usefully carried out co-operatively. There is, in the latter stages of this book, a description and analysis of two co-operative inquiry research groups (Heron 1996) that I engaged in with care managers in a different local authority from the first fieldwork event. Both the process and outcomes of these inquiries have proved very fruitful in extending understanding of the two major focuses for this book-the philosophical question of how we (best) construct useable knowledge, and the political question of how policy intentions can be realised through implementation practices.

I end with the writing of this book, as I started, in individual mode, making my own sense of the journey. One of the things I have discovered along the way is that unless we can apportion and combine our differing views, and work participatively towards a shared understanding, we lose two major opportunities. The first is the opportunity to acknowledge and respect other people and their difference. The second is to learn from difference, using knowledge created, in a continuous developmental practice. 'Research is for us' say Reason and Marshall (1987; p.112). 'It is a co-operative endeavour which enables a community of people to make sense of and act effectively in their world' (Reason and Marshall 1987; p. 112). These simple statements differentiate research as a participative process from the positivist approach of objective detachment of the knower from the known. Interestingly enough it also echoes much of the rhetoric of community care in the requirement on local authorities to establish the collective needs of the communities they serve. This rhetoric also speaks of services being determined by local authorities in collaboration with, and taking account of the expressed needs of, ordinary people in the community. It is this kind of congruence between different forms of knowledge that it is important for me to pursue. This is my purpose as a learner and that is one of the reasons why I have followed the process which has been described. Reason and Marshall (1987) point out that research needs to speak to three audiences-for them, for us and for me. For my own integrity I have learnt that this is the way I need to do it, for the sake of authenticity I have learnt that it needs to be that co-operative endeavour-creating useable knowledge together. If others wish to use the results of research, how much better that they should understand that it was founded on an 'authentic and complementary research process' (Reason and Marshall 1987; p.113).

Reflexive and Reflective Research-Justification of Process

An explanation of the process of the research as revealed in this book is important at this stage. A book should not just be a piece of academic output but should reveal the author as a learner. This is not a post-hoc rationalisation, but reflection on a process of inquiry and learning. I am persuaded of the need to be both reflective-'showing ourselves to ourselves' (Steier 1991; p. 5) and reflexive-'being conscious of ourselves as we see ourselves' (Steier 1991; p. 5). There are powerful arguments in professional practice (Boud et al 1985; Schon 1984; Schon 1987; Gould and Taylor 1996) that practitioners such as social workers should be reflective both in and on their practice. Researchers are no different in this case and we will look at that later in this section.

To be reflexive 'implies that the orientations of researchers will be shaped by their socio-historical locations' (Hammersley and Atkinson 1995). To be 'insulated' (Hammersley and Atkinson 1995) or disclocated from the object of one's research, or to pretend that we can be objective in that sense is to construct an inauthenticity which is likely to undermine any validity claims. My reflexiveness has been continuous throughout the process of the research. It is helpful to take a moment to record this because of the degree to which my understanding of my part in the construction of research findings has affected and shaped the process of the research. I have been reflexive about my position not only as a researcher and academic but also as a teacher of social workers and as an expractitioner and manager of social work. All these factors influence my perspective on the subject in question.

My 'socio-historical location' as a researcher is affected by the weight given to research within an academic environment. This plus the marginalisation of social work research within a School of Social Science, and Social Science within a broader technical University provides a pressure on the social work researcher which is palpable. How is it possible to prove oneself as a real researcher in this context? This, plus my awareness of the traditions of research in the social work arena were hard to ignore. The safety of the positivist paradigm in social research, and the tradition of qualitative research methodology heavily influenced my entrance into the first fieldwork component of this research. This becomes part of the explanation if not the justification for qualitative research interviews which are described and analysed in Chapter Three. Reflexiveness is a permanent revolution, however, and, along with the reflection which I will describe below, induced the realisation that there were different ways of understanding social research. Modernist and Post-modernist analysis of social work practice and theory (Parton 1994: Howe 1994) plus the literature around participative action research methodology (Reason et al 1981) enabled me to understand a different way of seeing myself as a social work academic in my 'socio-historical location'.

As an ex-practitioner and manager, and as a te...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. General Introduction - Reflecting on the Process

- 2. Policy Implementation and Community Care

- 3. Care Management and the Subversion of Policy

- 4. Key Texts that define Community Care

- 5. Lipsky and Street Level Bureaucrats - a Source of Explanation

- 6. Management and Managerialism

- 7. Care Management and Social Work Theory

- 8. Participation and Action Research - a Coherent Framework for Understanding

- 9. Care Managers Investigate their own Practice

- 10. Policy, Discretion and Learning in Organisations

- Bibliography