- 214 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Measurement and Development of Empathy in Nursing

About this book

This title was first published in 2000: Empathy is known to be crucial to helping relationships, but professional helpers, including nurses, do not normally display much empathy as it has not been measured in clients' terms and accordingly taught. This text examines a study in which a client-centred empathy scale was developed - the client-centred measure of empathy was found to be reliable and valid and a course designed to teach nurses to offer empathy in clients' terms was effective. The findings of the study have implications for the future design of nurse eduction and the goals of the health service.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Measurement and Development of Empathy in Nursing by William Reynolds in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Empathy is crucial to helping

The literature reviewed in this chapter substantiates the widely held view that empathy is crucial to all forms of helping relationships. Additionally, while there is confusion about whether empathy is a personality dimension, an experienced emotion, or an observable skill, it is shown that empathy involves an ability to communicate an understanding of a client's world. Finally, the definition of empathy used in this study is introduced. This definition is relevant to the goals of clinical nursing, which include the need to understand clients' distress, and to provide supportive interpersonal communication.

1.1 Why empathy is crucial to helping

In this section, it will be shown that:

- empathy is crucial to all helpful interpersonal relationships;

- the purpose of helping relationships is emphasised by a definition of the helping relationship cited in this section;

- the purpose includes: i) the development of a safe interpersonal climate and, ii) to enable clients to cope more effectively with threats to their health;

- several studies indicate that empathy enables professionals to appreciate the client's perspective and to respond in ways that result in favourable outcomes for those seeking help.

An extensive argument can be found in the literature to support the view that helper empathy is an important facilitator of constructive interpersonal relationships. While referring to the helping relationship in the contexts of clinical psychology, nursing, and medicine, Truax (1970) emphasised that without empathy there is no basis for helping. This view has been repeated by many other writers. Thus Kalish (1971) wrote:

a voluminous amount of the accumulated research and theoretical findings on interpersonal relationships supports the idea that empathy is the most critical ingredient of the helping relationship (p 202)

and Carver and Hughes (1990) (in the context of intensive care units):

the sterility of a mechanical (high technology) environment makes the caring, comforting functions of professionals critically important, yet difficult to achieve, Technical competence is necessary, but must be combined with interpersonal skills such as empathy, warmth and respect, before the patient feels health professionals care (p 15).

1.1.1 The purpose of the helping relationship

To consider the implications of the available research evidence supporting the hypothesised relationship between empathy and helping, it is useful to review the intended outcomes of the helping relationship. Irrespective of whether the helping process is referred to as counselling (Anthony, 1971), psychotherapy (Truax and Mitchell, 1971), human relations (Gazda et al. 1984), therapeutic relationships (Kalkman, 1967), interpersonal relations (Peplau, 1988), teaching (Chambers, 1990), or simply caring (Watson, 1985), all writers refer to similar aims or purposes. These include: i) initiating supportive interpersonal communication in order to understand the perceptions and needs of the other person, ii) empowering the other person to learn, or cope more effectively with their environment, and iii) the reduction or resolution of the problems of another person.

Kalkman (1967) who refers to the helping relationship as relationship therapy, provided an operational definition of the nurse-client relationship which includes aims and purposes that are likely to be common to all helping disciplines. She states that:

relationship therapy refers to a prolonged relationship between a nurse-therapist and a patient, during which the patient can feel accepted as a person of worth, feels free to express himself without fear or rejection or censure, and enables him to learn more satisfactory and productive patterns of behaviour (Kalkman, 1967, p 226).

Kalkman's (1967) definition of the helping relationship is congruent with those provided by numerous other theorists (eg. Peplau, 1952; Rogers, 1957; Ashworth, 1980; Wilson and Kneisl, 1983; La Monica, 1987). This definition provides a useful basis for commenting on the research concerned with the efficacy of empathy in the interpersonal process. A review of the literature suggests that there are considerable grounds for accepting the view that empathy is a critical variable in determining the outcomes postulated by Kalkman. While the available research evidence is not necessarily conclusive, numerous contributors to the literature on interpersonal relations have found it persuasive.

1.1.2 The importance of a supportive interpersonal climate

Kalkman (1967) states:

relationship therapy refers to a prolonged relationship between a nurse therapist and a patient, during which the patient can feel accepted as a person of worth, and feels free to express himself without fear of rejection or censure... (p 226).

In relation to this view, several studies have suggested that empathy can help create an interpersonal climate that is free of defensiveness and that enables individuals to talk about their perceptions of need. The difficulty in drawing firm conclusions from these studies is partly related to the fact that researchers have measured empathy differently. While most studies have defined empathy in a cognitive-behavioural way, the use of different measures means that the construct being measured among studies is not necessarily the same. A review of a sample of the available studies emphasises this point.

A study by Mitchell and Berenson (1970) viewed empathy in a cognitive-behavioural way, as operationalised by the Truax Accurate Empathy Scale. With respect to confrontation of unpleasant or maladaptive behaviour, these researchers found that during the first counselling session, highly-empathic therapists, significantly more than low-empathy therapists, used approaches which provided important information about the therapist, focused on the here-and-now relationship between therapist and client, and emphasised the client's resources. On the other hand, low-empathisers were more likely to confront clients with pathology rather than with their resources.

A study by Reynolds (1986) reported that as clients' ratings of student-nurse empathy increased among repeated measures on the Empathy Construct Rating Scale (La Monica, 1981), their anecdotal descriptions of the students' behaviour during a series of counselling interviews suggested that they felt more able to be open with their student. Typical examples included: "It's hard for her to understand me, but she is trying very hard" (second counselling interview), "I can talk freely to her, there is no barrier" (fifth counselling interview).

While there is a danger that clients might say what they think that people want to hear, the specific nature of clients' comments suggested that they experienced sensitive understanding from the students and became less defensive. In spite of the possible limitations arising from social desirability factors, these data encourage the idea that trust was developing in the relationship as a consequence of nurses' attempts to understand their clients.

Howard (1975) interviewed clients in several clinical settings in order to investigate the conditions perceived to be necessary for humane care. Analysis of the interviews, observation of nurse-client interactions and the literature on personalised care led Howard to identify cognitive behavioural empathy as a necessary variable for humane care. Howard reported that empathy helps professionals respond to clients as unique human beings because they can see the world from the vantage point of their client, and better understand and respond to their needs.

Lyon-Halaris (1979), commenting on non-verbal behaviour, reported that low-empathy nurses mainly exhibited listening via non-verbal behaviour, for example, avoidance of eye contact, eyebrows down, wrinkled forehead and the crossing and uncrossing of legs. High-empathy nurses were also reported to laugh significantly less than low-empathy nurses. Following the interviews, clients completed the Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory (Barrett-Lennard, 1962), a client measure of cognitive-behavioural empathy, rating the degree of empathy they felt from nurses. An analysis of variance determined high and low-empathy nurses (p<.05); 3 nurses were highly empathic and 2 were not. The researcher then compared the frequency and duration of non-verbal behaviours for high and low-empathy nurses. While differences were found between high and low empathisers in terms of non-verbal behaviour, the only significant findings from a test of the difference in mean frequency related to laughter (p<.02) and leg movements (p<.01).

A limitation of this study is the small sample (n = 5). However, it is of interest because the client sample reported that the non-verbal behaviours of low empathisers tended to convey a lack of respect, interest and support. Interest and support seem similar to Rogers' (1957) concept of warmth. Absence of commitment from the helping person is likely to interfere with the development of trust in the helping relationship. To trust another person with personal information requires that the client believes that the information will only be used for the purpose for which it was given (Ritter, 1994). Absence of trust is likely to act as a barrier to empathy because it is less likely that a client will be open and sharing with information.

The creation of an initial interpersonal "climate" that is free of defensiveness would seem highly desirable in view of the fact that health professionals have the arduous task of conveying emotionally charged information to the public. Fear, anger and misconception lead some professionals to respond in a discriminatory manner to clients with socially undesirable problems (see Haines, 1987). These issues include problems of family violence, child abuse, wife battering and abuse of the elderly. Group self-help approaches recommended by Petit (1981) and Valenti (1986) have been demonstrated to require empathic skills to encourage sharing and openness among group members.

1.1.3 Empathy and therapeutic outcomes

Kalkman's (1967) description of the helping relationship also suggests that it is a purposeful activity which has as its final objective, client growth. She states that:

relationship therapy...enables the client to learn more satisfactory and productive patterns of behaviour (p 266).

Several studies have supported the hypothesised relationship between empathy and favourable health outcomes for clients.

Feital (1968) pointed out that numerous studies have established a correlation between empathy, the helping relationship, and measures of outcomes such as improved health or more effective learning. Truax and Mitchell (1971) cite more than a dozen studies supporting their belief that empathy is a major determinant of successful outcomes for clients in counselling and psychotherapeutic situations. Rogers (1975) reiterated once again his belief in the crucial role of the empathic process when the other person is 'hurting'. He summarised a sample of 22 research findings that support his belief.

Since Rogers' (1975) paper, the research evidence has accumulated, and studies have supported the view that empathy is a primary ingredient in helping relationships (eg. Gladstein, 1977; Coffman, 1981; Altman, 1983; McKay et al., 1990). However, the nature of inquiry is one in which facts are not treated as self-evident givens (Schwab, 1962), and some studies showing conflicting results suggest that the debate has not yet ended (eg. Hart, 1960; Sloane et al., 1975; Rocher, 1977; Newall, 1980).

At best it can be said that the majority of the studies conducted over the past four decades have supported the hypothesised relationship between empathy and the ability to help another person. In nearly all cases empathy has been conceptualised in a cognitive-behavioural manner, relying on client-reports or ratings by objective judges.

The results reported so far are congruent with many other studies. For example, Siegal (1972) found improvement among children with learning disabilities in both verbal and behavioural spheres related to time in play therapy, and therapists' levels of empathy, warmth and genuineness. Additionally, Kendall and Wilcox (1980) demonstrated a significant relationship between empathy and therapist effectiveness during their treatment of hyperactive and uncontrolled children.

Evidence that empathy may be a more important facilitator of a helpful relationship than the helper's ideological orientation came from a study by Miller et al. (1980). This study found that behaviour therapists who scored high in empathy, were more potent reinforcers of adaptive behaviour than therapists who were low empathisers.

In his later years, Rogers extended his theory of client-centered psychotherapy to other situations such an encounter groups and play therapy. He also became interested in the application of his theory to education and extended it to interpersonal relations in general (eg. Rogers, 1960 and 1977). This resulted in empathy research extending into the student-teacher relationship. For example, a study by Aspey (1965) found that in three classes where the teacher's empathy was highest, the pupils showed a significantly greater gain in their reading achievement than in those classes with a lesser degree of that quality. These findings were consistent with an enlarged study be Aspey and Roebuck (1975) that extended for more than a decade. The evidence that they accumulated suggests that the attitudinal climate of the learning environment, as created by the teacher, is a major factor in promoting or inhibiting learning (Hughes and Huckill, 1982).

The role of empathy in the helping process requires further investigation against specific outcome criteria. However, in spite of the conflicting results among studies, the specific positive effects of empathy upon the needs of helpers remains a reasonable proposition. This is of interest to nurse educators because of the widely accepted view that empathy is crucial to effective interpersonal processes and essential at the onset of a relationship (eg. Mitchell and Berenson, 1970; Gazda et al. 1975; La Monica et al. 1987; McKay et al. 1990; Graham, 1993). Further research evidence is commented on in Chapter 2 that supports the need for empathy in clinical nursing.

1.2 The meaning and components of empathy

In this section, it will be shown that:

- there is a debate around empathy as a personality dimension, an experienced emotion, or an observable skill;

- empathy needs to involve the client's actual awareness of the helper's communication in order that clients know whether they are being understood;

- accurate empathy is a form of interaction, involving communication of the helper's attitudes and communication of the helper's understanding of the client's world;

The need to find a common definition of empathy is emphasised by the disagreement in the literature about what empathy means. Empathy has been variously conceptualised as: i) a behaviour, ii) a personality dimension, and iii) an experienced emotion (McKay, 1990). During the past decade, several writers (eg. Davies, 1983; Williams, 1990; Morse et al. 1992; Bennett, 1995) have suggested that as a result of the complexity of the empathic process, confusion exists about the meaning and components of empathy. These writers propose that empathy is a multidimensional, multiphase construct which is often considered in a narrow way as a unitary construct.

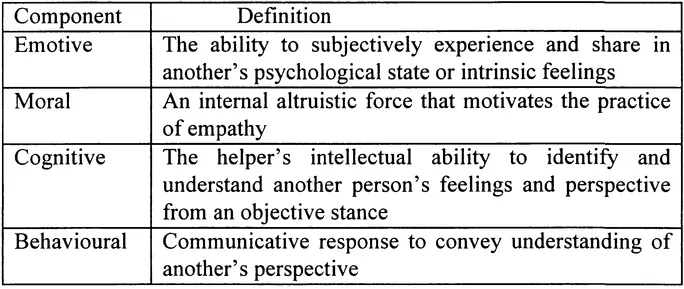

Following an extensive review of the literature, Morse et al. (1992) identified four components of empathy: moral, emotive, cognitive and behavioural (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Morse's components of empathy

Similarly, Williams (1990) informs us that the most...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Empathy is crucial to helping

- 2 The problem: Professional helpers, including nurses, do not normally display much empathy

- 3 Analysis: Empathy has not been measured in clients' terms and accordingly taught

- 4 Solution, Part 1: A reliable and valid client-centred empathy scale has now been developed

- 5 Solution, Part 2: Using this scale, a course has been developed which does help nurses to show empathy

- 6 Summary and implications: Such a course may help others to learn as well

- Bibliography

- Appendices 1 The empathy scale and users'guide

- Index