eBook - ePub

Agricultural Policy Reform

Politics and Process in the EU and US in the 1990s

- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Agricultural Policy Reform

Politics and Process in the EU and US in the 1990s

About this book

This title was first published in 2002. This engaging work examines the interplay between US and EU agricultural trade policy reforms, as well as the linkage between domestic and trade policy reform, and addresses whether reform is likely to continue during the first decade of the 21st Century. Features include: - Comprehensive overview of the interplay between domestic and international agricultural policy reform - Detailed analysis of the paradigm shift in policy - Vigorous discussion of the potential impact of emerging issues such as GMOs, intellectual property rights, animal and plant health, and human safety The book offers a rich empirical account of politics and diplomacy over the last decade, providing an important background for explaining forthcoming agricultural policy debates in the US, the EU and agricultural policy negotiations in the WTO.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Agricultural Policy Reform by Wayne Moyer,Tim Josling in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Agricultural Policy Reform in the US, EC/EU and GATT/WTO

Industrial country agricultural policy in the post-World War II era has been highly protectionist, commodity based, market distorting and dominated by domestic politics. The agricultural sector has therefore lagged behind in the general trend of deregulation and market liberalization that has permeated most sectors of the economy. The problems this has created have spilled over into the international arena. Subsidies have been paid to farmers largely on the basis of production and financed by consumers, leading to the build-up of embarrassing surpluses, the disposal of which has proved increasingly disruptive to the international market for agricultural goods. The United States and the European Community (EC) can share much of the blame for the export of the surplus capacity, though major importing countries such as Japan have kept many of their markets closed and smaller countries have also maintained high support levels for many crops.1 By the mid 1980s, the costs of agricultural policy in many countries had grown to unacceptable levels, and the disruption of agricultural markets had created international conflict.

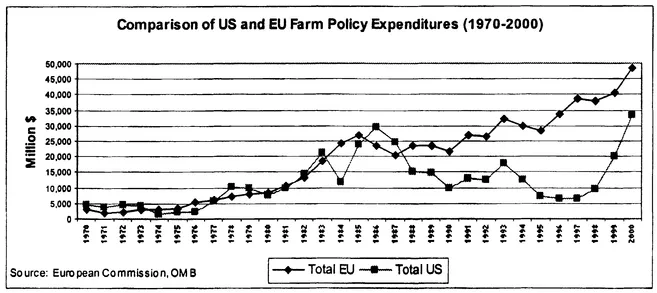

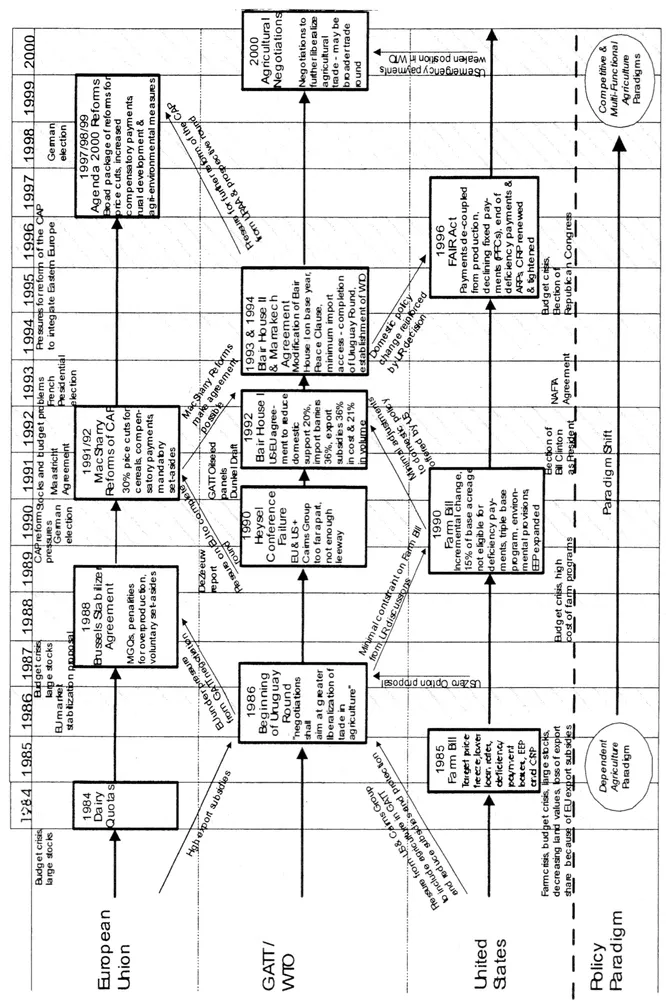

As a result of increasing costs and market disruption, both the EC and US began to undertake reform of their agricultural policies. The policy changes in the 1980s were analyzed in a previous book (Moyer and Josling, 1990).2 During the 1990s, more significant reforms were undertaken in both Europe and America, accompanied by the inclusion of agriculture into the liberal international trade regime of the World Trade Organization (WTO). We have diagramed these changes and the interplay between domestic and international reform in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.1: Comparison of US and EU Farm Policy Expenditures (1970-2000)

These reforms, overall, have significantly liberalized agricultural policy, but have not succeeded in stemming the growth of government farm spending.3 Indeed, the continuing high cost of government support for agriculture has provided a strong impetus for successive reform efforts.

In our earlier work, we analyzed the reforms of the 1980s. This book will explain in detail the progression of domestic farm policy reforms in both the US and EU for the 1990s, the international agricultural trade reforms in the GATT and WTO, and the interplay between domestic and international reforms. What provided the impetus for each reform? How does one explain the timing and content? How did the reforms of the 1990s follow from those of the 1980s? Why have the reforms generally been liberalizing with greater market orientation and the de-coupling of government farm payments from production? But, why has liberalization not gone even further? Why, with the farm population declining in both the US and EU, have policy-makers been unable to control farm spending?

A number of previous works have attempted to explain agricultural policy reform. Writing for the 1980s, Moyer and Josling (1990) saw reform in the US and EU driven by budget pressures, but slowed by compartmentalized policy processes dominated by the farm policy community. For the 1990s, a number of scholars have shown that the MacSharry reforms were driven both by international pressures generated by the Uruguay Round trade negotiations and by the domestic unsustainability of the CAP (Tangermann (1998), Swinbank and Tanner (1997) Coleman and Tangermann (1997), Patterson (1997). These authors also see the completion of the MacSharry reforms as instrumental for the successful completion of the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture. Patterson explains the linkage between domestic and international reform in terms of multi-level bargaining games, while Coleman and Tangermann see the influence of intersecting CAP and GATT games. Webber (1997, 1998) argues that both CAP reform and the GATT negotiations were strongly influenced by intergovernmental politics between France and Germany. Vahl (1997) makes the case that the supra-national EC Commission played a critical leadership role in negotiating a GATT agreement acceptable to the EU and in then selling that agreement to member states. Coleman, Skogstad and Atkinson (1997) find that a shift in thinking about agriculture policy from a state-assisted paradigm to a market liberal paradigm is associated with agriculture policy reform in the US, EU, Canada and Australia. They note that corporatist policy networks lend themselves to a cumulative, negotiated, problem-solving trajectory to paradigm change whereas state directed or pressure pluralist networks are more likely to be associated with crisis-driven change. Coleman, Atkinson and Montpetit (1997) conclude in their study of agriculture policy during the 1990s in the US, EU and France that systemic retrenchment and obfuscation helped governments overcome the resistance of entrenched farm lobbies in producing significant policy change. They also find that when agriculture was introduced successfully into international trade negotiations, the domestic rules of the game and players at the table were reconstituted in ways that promoted reform. Finally, they note the importance of two systemic variables – rules and practices that structure the roles of groups in policy-making, and the ideological position of the ruling party in the legislature – in explaining farm program change. Orden, Paarlberg and Roe (1999) downplay the importance of the Uruguay Round in promoting US agricultural policy reform in the 1996 FAIR Act, arguing that the election of a Republican congress in 1994 and rising commodity prices were far more important.

All of these works provide valuable insights. However, each represents only a partial analysis focusing on specific policy decisions rather than examining the full progression of policy reforms in the US, EU and the GATT between 1980 and 2000. Ingersent and Rayner (1999) provide an excellent overview of reform during the entire time period, and for an even longer time span, identifying the economic trends that promoted change. But they do not consider the process and politics shaping the reforms that finally emerged. This book will contribute a more complete explanation of how politics and process, influenced by past policies, national and international economic trends and political developments, shaped farm policy reform.

1.2 The Progression of Agricultural Policy Reforms in the US, EC/EU and the GATT/WTO

Before discussing in detail our argument, it may be helpful to layout in sequence the various steps toward policy reform in the US, EU and the GATT between 1980 and 2000.4 The first important development in this time period came when the EC, facing a farm spending crisis, took a significant step toward policy reform with the decision in 1984 to impose dairy quotas (see Moyer and Josling, 1990, Petit, 1987). This did little to liberalize trade in dairy products, though it did reduce EC milk surpluses and stabilized expenditures for dairy support. The US farm crisis of the mid-1980s contributed both to the reforms in the 1985 US Farm Bill and to the efforts to liberalize agricultural trade in the GATT Uruguay Round negotiations. The US had lost export market share partly as a result of the strong dollar, partly because loan rates had been set too high in the 1981 Farm Bill, and partly because of EC competition fueled by export subsidies (see Moyer and Josling, 1990, Chapter 9).

With GATT negotiating differences with the EC so pronounced, the US was not under much pressure to liberalize agriculture policy in the 1990 farm bill, which was completed just before the Heysel Conference. In fact, the bill provided for increased subsidies through the Export Enhancement Program as a "bargaining chip" to pressure the EC to agree to reduce export subsidies in the GATT negotiations (Orden, Paarlberg and Roe, p.98). However, a liberalizing impetus was created by the large US budget deficit, which led to the establishment of the "triple-base" program, dividing farmer's base acreage into three categories: land with crops eligible for deficiency payments; required land set-aside under the Acreage Reduction Program (ARP); and 15 percent of base acreage on which farmers could grow whatever they wanted, but not receive deficiency payments.

The MacSharry reforms, along with the reports of two GATT panels that ruled against EC oilseed subsidies, made it possible for the US and EC to bridge their differences, and reach the Blair House I agreement in November 1992.5 Domestic support was to be reduced 20 percent, tariff barriers cut by 36 percent and export subsidies reduced by 36 percent in expenditure and 21 percent in volume. Both parties agreed to create a new "blue box" for US deficiency payments and EC compensatory payments, not subject to challenge in the GATT for a period of time (the Peace Clause).6 This agreement was unacceptable to the government of France, facing angry farmers in a tough parliamentary election campaign. Following the victory of the conservatives in the election, the French were able to force further negotiations. These negotiations produced the Blair House II agreement in December 1993, which dealt with French objections by extending the Peace Clause from six to nine years and by delaying export subsidy cuts to allow the EU to dispose of its stocks without a collapse in prices. This agreement was accepted by the other parties of the GATT, thus allowing the Uruguay Round to be completed with the March 1994 Marrakesh agreement, and the creation of the World Trade Organization.

With the 1990 US Farm Bill about to expire, debate on new farm legislation began in early 1995. The Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture (URAA) provided only minimal constraints to the debate in that the domestic support reductions of the 1990 Farm Bill met URAA requirements, while export subsidies had declined due to increasing world prices. However, the Uruguay Round enhanced the attractiveness of liberalized domestic policy in that it portended greater openness in international markets. The Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform (FAIR) Act, approved in April 1996, marked a significant liberalizing departure from previous farm legislation. It de-coupled farm payments from production by abolishing deficiency payments and ARP set-asides. Farmers could grow whatever they wanted on their land, and receive whatever they could get in the market. To cushion the adjustment, they would receive acreage based compensatory payments, adjusted for average yields over the previous five years, under Production Flexibility Contracts, These payments would gradually decline over the six years of the farm bill's duration.

The FAIR Act has not played out as intended. Conceived at a time when farm prices were high, it was anticipated that the costs of farm support would decline over time, even though they would rise in the short run. However, the sharp decline in world prices led to the US congress to pass emergency farm bailout measures in 1998, 1999 and 2000, which have produced the largest levels of farm support ever, reaching $28 billion in 2000.

The FAIR Act, by de-coupling farm payments from production, served notice to the EU that the US would be willing to abolish the "blue box" in the next round of WTO agricultural trade negotiations due to begin by the end of 1999. Moreover, the EU had other reasons to undertake further reforms. Agricultural spending had actually increased after the MacSharry reforms, and would continue to increase, without further policy change. None of the EU members was willing to pay the increased cost, particularly Germany, the largest contributor, which was burdened by the huge expense of integrating former East Germany. Another impetus was the prospective entry into the EU of the former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Extending the MacSharry compensatory payments to these countries would break the CAP budget. Projections showed that EU export subsidies would soon exceed Uruguay Round limits and would have to be reduced.

The EU Commission, recognizing the realities, proposed an Agenda 2000 reform package in June 1997. This proposal continued and intensified the MacSharry reforms, calling for further significant price cuts for cereals, oilseeds and beef, with reduced support for dairy and increased compensatory payments. There was also a new emphasis on spending for rural development and agri-environmental measures. The Agenda 2000 package was finally approved by the April 1999 Berlin summit, after the price cuts were weakened and the dairy reforms delayed.

Figure 1.2: Comprehensive View of Agricultural Policy Reform in the US, EU and WTO (1984-2000)

The WTO agricultural trade negotiations began seriously in the summer of 2000 after being side-tracked by the break-down of the Seattle Conference in November 1999. As in the Uruguay Round, there are serious negotiating differences between the US (and the Cairns Group) on the one hand and the EU on the other.7 The US proposes further liberalization through the reduction of tariffs and the elimination of export subsidies and would limit agricultural spending to a proportion of total production. The EU, though willing to contemplate further reductions in domestic supports, import barriers and export subsidies, insists on retaining the "blue box" for compensatory payments. It also wants recognition of the multi-functionality of agriculture. This would exclude from WTO disciplines payments to preserve the country-side, small towns and villages, or to compensate farmers for the loss of market share to those whose costs are lower as a result of not having to provide these public goods.8

There are a number of puzzles in this reform sequence that this book will attempt to explain. Why, for example did US and EU policies tend to converge? Is there any reason to believe that these policies will converge further in the future, or are they likely to diverge? Why did agricultural policy expenditures in the EU increase after the approval of the MacSharry reforms and in the US after the FAIR Act? To what extent did the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture constrain subsequent domestic agricultural policy reform in the US and EU? Is the WTO process likely to constrain future reform?

1.3 The Analytical Framework

In our previous book, we examined the steps toward US and EC agricultural policy reform in the 1980s using an analytical framework that explained the decision-making process operating in response to a wide range of factors. These included economic trends and shocks, political developments, group and national interests, outside political inputs (lobbies, academic writings, pressures from allies and other trading partners), inside political inputs (the positions of various political actors and how they are formed), and the interplay between different actors (see Moyer and Josling 1990,Chapter 1). We analyzed decision-making using a series of conceptual models including rational national actor, public choice, organizational process, bureaucratic politics and partisan mutual adjustment. In this book we will build on this conceptual framework, adding to our conceptual focus the nature of paradigm shifts, the importance of path dependency analysis, and the importance of multi-level and linked bargaining games.

1.4 Central Themes i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Boxes

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: The Analytical Framework for Farm Policy Reform

- Chapter 3: The Search for an Agricultural Policy Paradigm Shift

- Chapter 4: Reform Frustrated: The Uruguay Round, 1986-1990

- Chapter 5: The 1990 US Farm Bill – Reducing the Budget, but Minimizing the Pain

- Chapter 6: The 1992 MacSharry Reform of the CAP

- Chapter 7: Reform Revived: The Dunkel Draft, the Blair House Accord and the WTO Agreement on Agriculture

- Chapter 8: The FAIR Act of 1996 – Decoupling Payments from Production

- Chapter 9: Agenda 2000-New Reforms for the CAP

- Chapter 10: The 2000 Agricultural Negotiations

- Chapter 11: Reform Compared: Similarities and Differences between the US and EU

- Chapter 12: The Future of Agricultural Policy Reform in the EU and the US

- Bibliography

- Index