- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cluster Development and Policy

About this book

This title was first published in 2002. Examining cluster development policy in Europe and outlining its distinctive features, this innovative text places it within the national context of regional policy-making. It also identifies the features supporting the successful development of industrial clusters and provides a clear overview of cluster theory and policy practice followed by seven key case studies on the history and operation of different cluster policies in Europe. While there has been a number of books on the theory of cluster development little research has been published on policy. By filling this gap, this book will be of interest to a policy-making audience as well as students and researchers of regional economic development throughout Europe.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Philip Raines

Few phenomena have marked discussion of economic development in recent years so much as the interest shown in the 'cluster' concept. Publicised by the work of Michael Porter and others, the proliferation of work on clusters and cluster-based policies points to one of the most dynamic exchanges between economic development theory and practice for several decades (Porter, 1990a; Held, 1996; Rosenfeld, 1997; Steiner, 1998; OECD, 1999; den Hertog, Bergman and Charles, 2001; Mariussen, 2001). As a result, there is a growing, widespread belief among policy-makers worldwide that clusters can form the basis of a successful economic strategy by supporting regional innovation, encouraging technological spillovers, producing economies of scale and scope and enhancing self-sustaining local economic development. At the same time, questions have been raised about whether the theoretical underpinnings and policy applications of the cluster approach are little more than 'old wine in new bottles', not so much borrowing from as re-labelling existing ideas. Nevertheless, whether hailed as a critical shift in policy understanding or criticised as a false panacea, it is difficult to deny that the approach to cluster development and policy represents a uniquely vigorous interaction between the academic and policy-making spheres.

Although definitions vary, clusters can be thought of as networks of firms, research institutes and public bodies, which tend to be located in relatively close geographical proximity and whose cross-sectoral linkages generate and renew local competitive advantage. In this, the cluster concept is not immediately novel. In economic development literature, the fundamental links between economic agglomeration and competitiveness are long-standing, dating back to Alfred Marshall in the late 19th century (Marshall, 1961), if not earlier. Studies of successful regional economies over the past few decades have regularly uncovered elements of clustering, ranging from the local webs of small, crafts-based enterprises in the northern Italian industrial districts to the international concentration of high-technology companies in Silicon Valley, from competitive networks of agro-businesses in the rural regions of Denmark to web design and multimedia firms in New York city.

Nonetheless, discussion of the validity and implications of the cluster concept has introduced two key important elements into economic development. First, it has brought together a series of earlier and parallel debates – including those relating to 'industrial districts', 'regional innovation systems' and 'learning regions' – and promoted a wider discussion of the sources of local competitive advantage. In this respect, the ambiguity of the cluster concept – often cited as a weakness – has surprisingly allowed a range of different economic development ideas to be combined in new configurations. It has not only raised interest in these ideas but helped to sharpen understanding of them.

Second, the policy implications of the cluster approach have been an integral part of the debate. While the role of policy intervention has only been discussed in economic development literature more fully in recent years, interest by the policy-making community in cluster development has been both intensive and pervasive. Over the last few years, there has been a dramatic proliferation of policies designed to promote development of clusters of firms and industries (or at least, purport to) (Enright, 2000). In Europe alone, cluster-based policies can already be found at national, regional and local levels in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the UK (case-study examples of seven of these are presented in this volume) and are in preparation in several other countries. Indeed, the annual cluster-related conferences organised by both DATAR and the OECD as well as the Competitiveness Institute have regularly attracted policy-makers from all over the world, pointing to a highly active global exchange of conceptual ideas and practical experience.

The debate has raised a number of more fundamental issues relating to the role of policy in economic development. In merging several different policy traditions, cluster policy has drawn attention to the need for a more comprehensive, integrated approach to local economic development and the growing importance of localised policy design and delivery (Nauwelærs, 2001). In requiring a more sophisticated, in-depth understanding of the operation of industrial clusters, it has led to a greater involvement of the private sector in policy-making, highlighting the blurring of boundaries between public and private areas of responsibility in policy (Raines, 2002). Most of all though, the central issue in the debate has been the extent to which the cluster approach represents a new model of understanding and shaping economic development. In tracing the influence of the cluster approach, a wide spectrum of opinion exists, summarised in the following three claims about its impact:

- cluster as a fad: the belief that the cluster approach adds little to the existing policy framework and can be discounted as a short-term bandwagon effect;

- cluster as a catalyst: where the cluster approach is seen to tweak existing policies and can inspire and channel new developments in policy rather than defining them (a form of 'Trojan horse' effect); and

- cluster as a paradigm: the view that the cluster concept has produced a radical and permanent shift in policy interventions in economic development.

'Fad', 'catalyst' and 'paradigm': the following volume aims to discern which of these descriptions best fits the way cluster policies have developed in Europe. It aims to do so by presenting original research on the emergence and operation of cluster policies in the following seven case-study regions, all of which have self-consciously adopted a cluster-based approach to economic development:

- the Arve Valley (France);

- Limburg (the Netherlands);

- North-Rhine Westphalia (Germany);

- Pais Vasco (Spain);

- Scotland (the UK);

- Styria (Austria); and

- Tampere (Finland).

While all seven regions are pursuing policies targeting industrial clusters, they have been selected with a view to demonstrating the diversity of approaches undertaken within a cluster policy framework. For example, there are differences in terms of the scale of policy, ranging from very large dedicated budgets for cluster development in Scotland and North-Rhine Westphalia (NRW) to far more limited ones in the Arve Valley and Tampere. The regions also vary in terms of their size (e.g. from a population of 60,000 in the Arve Valley to over 17 million in NRW), prosperity and industrial focus of the policy. Moreover, the policies do not necessarily share the same objectives with respect to cluster development. In cases like the País Vasco and Scotland, policy encompasses a wide variety of different aspects of building clusters, while other policies only concentrate on single aspects of cluster development, as in Limburg, where the focus is principally in developing project-based cooperation between firms. The variety should raise questions about the extent to which it is possible to discuss 'cluster policy' as an autonomous area of policy activity. Overall, the various approaches represent individual solutions to common challenges arising from their economic and policy environments.

Six of the case studies are based on research undertaken by the European Policies Research Centre at the University of Strathclyde in the context of the Euro-Cluster project. Funded by several European regional development organisations, the project aimed to identify and understand the key factors behind the successful design and delivery of cluster development policies. Fieldwork consisted of face-to-face interviews with the main policy-making participants in each area and analysis of associated strategies, evaluations and documents. The researchers are grateful to the sponsors for their support.1 In addition, a seventh case study – Styria – has been added because of the renown of the Styrian cluster approach and its contrasting experiences in pursuing development of two clusters (automobiles and wood products).

The book has been divided into two sections: a review of theory and a report on practice. In the first section, theoretical surveys are provided of the conceptual foundations to cluster development and the existing research understanding of the origins of cluster policy. The second section presents the seven case studies. The chapters broadly have the same internal structure, including a summary of the region's economic structure and main development challenges, the background on the emergence of cluster policy; the design of policy, a description of its content and delivery mechanisms, and lastly, an analysis of its impact on economic development approaches within the region.

Note

1 The sponsors were: Enterprise Ireland (Ireland); Scottish Enterprise (Scotland, UK); the Scottish Executive (Scotland, UK); the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Industry (Northern Ireland, UK) the Welsh Development Agency (Wales, UK); the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development (Norway); the East Sweden Development Agency (Östergötland, Sweden); and the Council of Tampere Region (Tampere, Finland).

Part 1: Theory

Chapter 2

Cluster concepts – the social engineering of a new regional institutional fix?

Peter Ache

Introduction

To give an overview of the theoretical debates behind the cluster concept and related models is a quite difficult task, given the duration of the debate and the evolutionary character of the concept itself, not least its derivatives (for an extended treatment see Lagendijk, 1999a), Its history dates back to the beginning of the 1990s, in particular the publication of the seminal book, The Competitive Advantage of Nations, by Porter (1990a). From there, the 'cluster' concept very quickly became the object of a wider debate. This debate focused on aspects of competition, innovation, economic and regional restructuring, spatial agglomeration, supply chains, small firm networks, industrial districts and the role of associations (Lagendijk, 1999a, p. 18). When examining the advantages of spatial agglomeration, the concept was also linked back to its oldest roots, the work by Alfred Marshall, in particular to his concept of the 'industrial atmosphere' affecting the competitiveness of localised industries (cf. Feser, 1998).

Further, policy-makers, being mainly interested in the application of the concept, developed it further in the course of setting up 'cluster (based or informed) initiatives' for national and later also regional and local economies.2 There was no single focus or even a single idea anymore. Instead, a flowing concept of different material, procedural and geographical orientations evolved, sometimes tailor-made for very specific national or regional contexts. Even more, looking at the academic actors, different professional backgrounds were involved such as geographers, policy scientists, economists and sociologists. Finally, industry itself has been closely involved in this debate – some of the cases introduced in this book are bottom-up initiatives led by industrialists.

The cluster concept has to be seen as part of a wider debate, which might be called 'new regionalism'. As Lagendijk (1998) critically commented, the new regionalism constitutes a larger agenda comprising concepts such as industrial districts, innovative milieus, regional innovation systems as well as clusters. All of these paradigms have been developed over the past decade (and slightly longer), focusing on one singular though encompassing question: that is, how can innovation in regional industries be stimulated and competitiveness be enhanced and ultimately maintained? In the current chapter, this question will be extended to the wider context, that is, the question of how can a general responsiveness to a rapidly changing environment, often labelled 'globalisation', be achieved?

The chapter will start with the description of Porter's concept and more recent extensions of his ideas. It will then turn towards the processes at work 'inside' clusters. Thereafter, different models of regional industrial organisation will be outlined, which provide an overview on the geographic reach of cluster structures. The last section will outline some conclusions.

Porter’s cluster model

Michael Porter's concept of clusters has been the most influential, not least because of its 'applied' and 'prescriptive' character (Lagendijk, 1998). The original cluster concept goes back to The Competitive Advantage of Nations.3 Using a number of case studies from different countries,4 Porter developed the core concept of the 'diamond of national advantage'. This concept will be introduced first – but only in brief, given the extended literature available, and thereafter, the question of geographical concentration will be addressed. Lastly, the core 'dimensions' of clusters will be outlined.

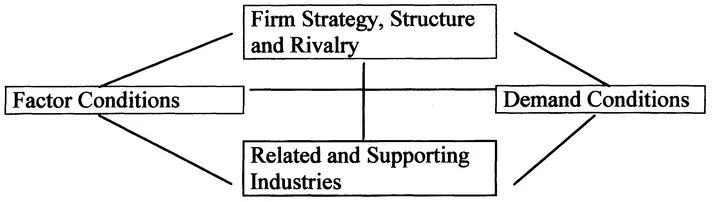

Porter's main concern was the competitiveness of industries or companies and the analysis of its constituent factors. When examining the foundations of national competitiveness, Porter (1990b, p.77) argued: "The answer lies in four broad attributes of a nation, attributes that individually and as a system constitute the diamond of national advantage, the playing field that each nation establishes and operates for its industries." The attributes are (cf. Figure 2.1):

- factor conditions: the nation's position in factors of production, such as skilled labour or infrastructure, necessary to compete in a given industry;

- demand conditions: the nature of home-market demand for the industry's product or service;

- related and supporting industries: the presence or absence in the nation of supplier industries and other related industries that are internationally competitive; and

- firm strategy, structure and rivalry: the conditions in the nation governing how companies are created, organised and managed, as well as the nature of domestic rivalry.

As Porter (1990b, p.77) explained:

Each point on the diamond – and the diamond as a system – affects essential ingredients for achieving international competitive success: the availability of resources and skills necessary for competitive advantage in an industry; the information that shapes the opportunities that companies perceive and the directions in which they deploy their resources and skills; the goals of the owners, managers, and individuals in companies; and most important, the pressures on companies to invest and innovate.

Figure 2.1: The diamond of national advantage

Source: Porter, 1990b.

Source: Porter, 1990b.

In addition, the diamond has a clear systemic character, which means that individual factors cannot be considered in isolation from each other. Porter makes this clear in his recommendations on what can be done by governments and companies in turn. On the contrary, it would be a misunderstanding of his model if actors simply try to provide factors in all these areas and in exactly the same way. Porter points out that in the current global competition, which includes amongst other things the possibility for companies to relocate productive activities on a global scale, it is rather a search for 'differential advantages', that is highly specific factor conditions and support structures, which have to be developed (see also Enright, 2000 on this aspect).

The differential advantages are a point of entry for local and regional circumstances or environmental conditions. As the title of Porter's book indicates, the concept in its original form focused on the national level, on states competing in a global market, and on firms or specific industries. The regional dimension (and the dimension of the city, Porter, 1995) was only established later on, and mainly in a debate led by geographers and regional economists.

Porter spoke about 'geographical concentration' while developing arguments for dynamic improvements, spurred by domestic rivalry (Porter 1990b, p.82):

Domestic rivalry... creates pressure on companies to innovate and improve. Local rivals push each other to lower costs, improve quality and service, and create new products and processes. But unlike rivalries with foreign competitors ... local rivalries often go beyond pure economic or business competition and become intensely personal... Geographical concentration magnifies the power of domestic rivalry.

The term domestic (and local) has no immediate geographical connotation at the outset, at least in the sense of a defined region. The regional geographic dimension...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- PART 1 : THEORY

- PART 2 : PRACTICE

- PART 3 : CONCLUSIONS

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cluster Development and Policy by Philip Raines in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Politica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.