eBook - ePub

Ethnocide: A Cultural Narrative of Refugee Detention in Hong Kong

A Cultural Narrative of Refugee Detention in Hong Kong

- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ethnocide: A Cultural Narrative of Refugee Detention in Hong Kong

A Cultural Narrative of Refugee Detention in Hong Kong

About this book

This title was first published in 2000: An ethnographic inquiry into the socio-cultural dynamics of the Vietnamese asylum seeker detention centres in Hong Kong during the period of 1988-1995. It deals essentially with the British asylum policy towards Vietnamese refugees and its outcome in Hong Kong. Based on the author's first hand experience of working in refugee camps, this book argues that the administrators managed to solve the crisis by perpetuating horrendous human rights violations and subsequent ethnocide of the asylum seekers trapped in the detention centres.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ethnocide: A Cultural Narrative of Refugee Detention in Hong Kong by Joe Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Hong Kong has had a long history of association with the Vietnamese asylum seekers. It began with the arrival of a Danish container ship ‘Clara Maersk’ on May 4, 1975, in Hong Kong. This container ship had an unusual cargo of 3,743 Vietnamese refugees who were rescued from the South China Seas. At a short notice camps were set up to house the refugees until they could be resettled abroad (this task was completed only by 1978). By then new asylum seekers began arriving in Hong Kong. The government’s declaration of ‘port of first asylum policy’ in 1979 solemnised the Colony’s initial flirtation and valour with the Vietnamese refugees. This was an open invitation to all Vietnamese seeking refugee status to use Hong Kong as a transit point for resettling in another country. This was an indirect result of USA and it’s allies’ futile war against Vietnam and their subsequent defeat at the hands of the Vietnamese army. This book traces the history of Vietnamese refugee issues in Hong Kong from its initial honeymoon period through various phases. The various stages includes the thawing of relations, chilled tolerance, irritation, separation, segregation, downright hostility, violence, and finally a ‘divorce’, scrapping the 19 year old ‘marriage’ with the first asylum policy for the Vietnamese refugees in 1998 by the Special Administrative Region (SAR) Government of Hong Kong. The core theme of this book is an analysis of the strategies adopted by the refugee managers to clear the so called ‘refugee problem’ in Hong Kong.

Background

Research for this book was conducted during a momentous period in the history of Hong Kong, the years leading up to the return of the territory to Chinese rule. It details and covers the experiences of detained Vietnamese refugees between the period of 1988-1995. One of the conditions of the transfer of power in 1997 between Britain and China was that the problem of the Vietnamese refugees/asylum seekers should also be ‘solved’. Ironically, during the same time it was forcibly repatriating the Vietnamese, Hong Kong was also importing skilled and semiskilled persons to meet its labour requirements.

What is in a name? The Vietnamese refugees who came to Hong Kong and other South East Asian countries to seek asylum have been described under various names during different periods of time. During the early part of the refugee saga all Vietnamese who managed to reach Hong Kong were called refugees. The popular media labelled them as ‘Boat People’. The administrators often used the acronym VBP (Vietnamese Boat People). In 1988, the government unilaterally ‘discovered’ that not all asylum seekers were genuine refugees implying that some of them were fleeing Vietnam due to economic reasons. They decided to implement a refugee screening procedure in Hong Kong to identify the so-called ‘genuine refugees’. This was the first sour note of the colony’s relation with the Vietnamese refugees. The Vietnamese who were identified as ‘genuine refugees’ were released from detention and were moved to another camp pending resettlement to another country. In early 1990, the Hong Kong government began referring to all asylum seekers as Vietnamese migrants. In this book I have used the term refugees and asylum seekers interchangeably, without particularly referring to their official status of refugee or non-refugee.

When hostilities between the United States and North Vietnam came to an end and Vietnam was unified in 1975, many former South Vietnamese political activists, administrators and soldiers left Vietnam to seek political asylum in other countries. They landed in many of the neighbouring South East Asian Countries, which served as a transit point for their subsequent resettlement in Western countries. Hong Kong was a ‘harbour of hope’ (Philpot, 1980) for many and provided refuge to thousands of asylum seekers from Vietnam since 1975. During the initial phase of Vietnamese asylum seekers exodus any Vietnamese who arrived in Hong Kong was automatically assigned refugee status. Most of the asylum seekers during that time were from the former South Vietnam. This arrangement continued for 13 years, till the midnight of June 15, 1988.

As the years passed, Vietnamese of Chinese origin also joined the railks of asylum seekers because of reported persecution and the ongoing power realignments within the united Vietnam. In 1988, many former North Vietnamese also began fleeing the country. There was a massive surge of humanity trying to escape Vietnam by any and all available means. Clandestine departures often resulted in extreme sufferings, breaking up of families and loss of lives. Such an influx of Vietnamese asylum seekers precipitated detention of asylum seekers in various camps across South East Asia. The social and political consequence of such a detention is one of the key phenomena explored in this book.

The first UN conference on Indo-Chinese refugees

For the first time in history, at the initiative of the USA and Britain, a special UN conference was held in Geneva to address the situation of the Vietnamese fleeting their country. Its agenda, which reflected cold-war politics, was to decide how to continue to ‘facilitate’ this outflow; to lay down the rules for the rescue of people at sea, who were increasingly in danger from un-seaworthy craft and pirates; and to convince other allies to accept a quota for resettlement in their countries.

The Voice of America (VOA) and the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) were ‘in charge’ of broadcasting information to Vietnam on the west’s resettlement policy and of the existence and location of the mercy ships. This open policy of encouraging the exodus of Vietnamese continued for 17 long years. The US ships were specially positioned at the South China Sea at the time to try and save the ‘boat people’ from pirate attack at sea. Even international humanitarian agencies like Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) chartered boats (L’ile de Lumiere) to rescue the boat people.

Because of the political temperature which had been raised all over the world during the Vietnam War, the response in the west to this ‘humanitarian crisis’ (a crisis fuelled for the benefit of cold-war objectives) was overwhelming and the media attention was intense. At the same conference, different countries established quotas for the number of Vietnamese refugees they would accept from the countries of first asylum.

The second UN conference on Indo-Chinese refugees

The second International conference on Indo-Chinese Refugees was also held in Geneva (13-14 June 1989) by the United Nations General Assembly. The mood of this meeting was quite different than the earlier one. By this time, with some exceptions, attitudes towards the ‘boat people’ had hardened. Hong Kong was already detaining refugees from 1982 and the automatic granting of asylum had ceased a year earlier. The agenda was to develop a framework to deal with the continuing influx of Vietnamese ‘boat people’. The Vietnamese ‘boat people’ were no longer described as a humanitarian crisis, but as a ‘boat people’ crisis. It was agreed that since Vietnamese were no longer automatically considered to be refugees, each and everyone would have to be ‘screened’, that is, to be put through a refugee determination status procedure in the countries where they sought asylum. Vietnam was asked to take back all those who were ‘screened out’.

This conference provided the framework of a ‘Comprehensive Plan of Action’ (CPA) to deal with this large influx of refugees from Vietnam. In addition, the Orderly Departure Programme (ODP) was established. It was designed to allow people to legally migrate from Vietnam, mainly to the Unites States. Under the CPA agreement, UNHCR was asked to monitor the procedures and a special monitoring committee was set-up. However, the implementation of the CPA varied from country to country.

Not every country detained Vietnamese asylum seekers, as did Hong Kong. Moreover, across the region, the refugee determination procedures were differently applied. In Hong Kong; the Immigration department under very minimal supervision of the UNHCR handled the refugee determination process. In Malaysia and Indonesia, the military took the primary role, although in Malaysia, the process did involve UNHCR staff. The issue of children without their parents also received different treatment depending on the country they were in. For example, the age of a child in Hong Kong was determined as anyone 16 or below at the date of their interview with an immigration officer. Others defined ‘children’ as those under 18 on the date of arrival in the camps. Around this period, with the gradual rapprochement with Vietnam, a separate agreement was reached to allow ‘Ameriasians’, the children (but not their mothers), who had been fathered by servicemen during the war to leave Vietnam for the United States.

The CPA was a bureaucratic solution for a humanitarian crisis. However, the authors of the CPA failed to anticipate the prolonged detention of a large number of asylum seekers. They also did not suggest any concrete measures to protect the best interest of the detainee’s by protecting their rights and privileges. Under the CPA, an agreement was reached concerning who was responsible for paying the cost of continuing to host the asylum seekers in the countries where they had landed to claim asylum. This responsibility explicitly fell on the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) in the case of Hong Kong. Later this became a bone of contention because UNHCR was reluctant to be seen to be paying for prison facilities in which asylum seekers were being detained.

UNHCR being an inter-governmental agency was expected to monitor the daily management of the asylum seekers and refugees. It’s other functions included searching for durable solutions and offering social services to the detainees. The Hong Kong Civil Aid Society (HKCAS) was the agency initially assigned by the government to deal with the refugee situation. Another local agency, ‘Caritas’, offered assistance for resettling the refugees in another country.

The British-Hong Kong Government subsequently passed specific immigration laws to determine the refugee claims of the asylum seekers of Vietnamese origin. These asylum seekers often waited up to four to five years to present their refugee claim to an immigration officer. Those waiting for the screening to determine their refugee status as well as those who had been ‘screened out’ and deemed as ‘non refugees’ were detained under the same legal framework and under the same conditions.

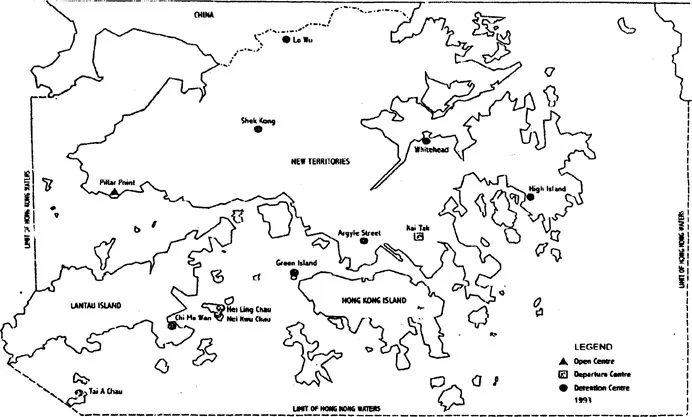

Detention camps for the asylum seekers in Hong Kong

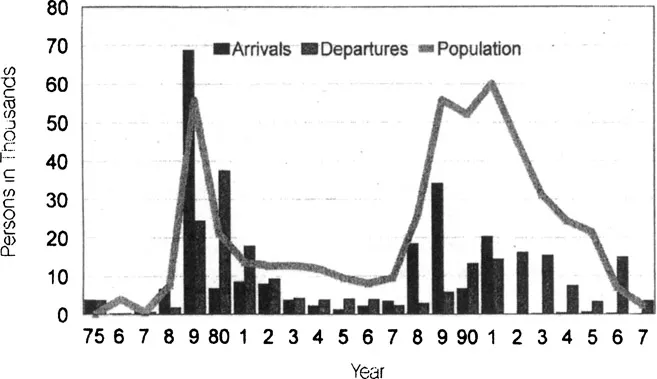

The Vietnamese detention camps were situated in remote islands faraway from the urban centres (Figure 1.1, Location of Vietnamese Detention Centres). These centres were inaccessible to the preying eyes of millions of tourist who visit Hong Kong every year, and also from the eyes of the local population. During the peak of the refugee saga in the late 1980s to early 1990s, the detention centres were home to some 50-60 thousand Vietnamese men, women, and children (Fig 1.2, Vietnamese Asylum Seeker Population in Hong Kong).

Figure 1.1 Location of Vietnamese Detention Centres

This unique social condition has led to several questions being raised related to the contemporary refugee policy, such as the role of international power relations in shaping the refugee movement, and the psycho-social consequences of detaining large numbers of people, including disabled, elderly, orphaned and abandoned children in appalling conditions. A descriptive ethnography of the socio-cultural conditions experienced by the Vietnamese asylum seekers detained in Hong Kong camps, and various other issues related to this phenomenon are the core theme of this book.

Figure 1.2 Vietnamese Asylum Seekers Population in Hong Kong

The Vietnamese asylum seekers were under the administrative custody of the British-Hong Kong Security branch which passed the responsibility of daily management of asylum seekers to the Correctional Service Department (CSD), Royal Hong Kong Police and a private company called the Hong Kong Housing Services for Refugees Limited. Since most of the asylum seekers came to Hong Kong in boats, an ambiguous term ‘Boat People’ has been used to denote all Vietnamese asylum seekers who arrived in Hong Kong. They were detained under what is known as Immigration (Vietnamese Boat People) Detention Centre Rules, which is essentially an adapted version of the British prison rule.

The detention centres where the Vietnamese asylum seekers lived was a different world by itself. Women, new-born babies, men, elderly, physically and mentally disabled, youngsters and children were barricaded within tall barbed wires. Some stayed on for six to seven years. Surrounded by the high security fence and observation towers, they walked around aimlessly like trapped animals inside the camps, or idled away their time by lying down in their bunks doing nothing in particular. Each family was assigned a bunk in a three-tier sleeping space. They were expected to sleep on a wooden plank without a mattress. The physical conditions in the camps provided very little privacy. The searchlights were always on. There was no partition to separate the bed spaces except for some cloth curtains for those who managed to get it from the camp charity workers. The food was centrally cooked and distributed. The role of the mother as the one who provides nourishment was watered down, as her caring role was minimal. The father was robbed of his authority as he was no more a bread winner and provider of the family. There were innumerable queues for everything, for food, drinking water, and the use of the toilets and washing facilities.

None of the asylum seekers were entitled to any special facilities or privileges. Despite this, the ‘Big Brothers’ formed an alleged collusion with the camp administration staff and enjoyed certain special privileges such as occasional food from outside the detention facilities, a can of beer or a cigarette. The elderly, the physically disabled and the children faced the same hurdles in their day-to-day life within the camp. They queued up for medical treatment or for an appointment with the agency staff for presenting any genuine request. Camp rules were often interpreted according to the whims and convenience of the low ranking functionaries. Most asylum seekers had never seen a copy of the rules under which they were detained.

Sense of betrayal

According to Leonard Davis (1991), the Vietnamese issue in Hong Kong can be divided into four periods:

- May 4, 1975, when the first group of 3,743 refugees rescued from the South China Seas landed in Hong Kong until July 2,1982, when the ‘closed camp’ policy was introduced;

- The initial six years of ‘closed camp’ era that witnessed a steady flow of refugees leaving for resettlement countries;

- The period from June 16, 1988 (the day on which the screening and repatriation policy came into operation) until the beginning of 1990 when it seemed that the Comprehensive Plan of Action endorsed by the international community was breaking down because of the inability of

- the British and Hong Kong governments to continue with mandatory repatriation, and the pressure from the Chinese government to abandon the policy of first asylum; and

- 4. The subsequent apparent disintegration - with the exception of voluntary repatriation - in the first six months of the new decade of many policy initiatives and earlier coping strategies.

This book also deals with another phase of the refugees, namely, the so called ‘non-refugees’. A large number of asylum seekers deemed as non-refugees (screened out) were reluctant to go home. They felt betrayed by the international community for changing the rules of the game by instituting a screening procedure, that many were unaware of when they left Vietnam to seek refuge in Hong Kong. Many refugees and refugee commentators believed the process of refugee status determination was riddled with flaws. The UNHCR suggested that it’s role with a ‘screened out’ population was limited and scaled down the social service facilities, citing resource crunch as one of the main reasons. However, most of the independent observer’s felt that it was a ploy to use cutbacks as a leverage to send the unwanted Vietnamese back home.

Scope of this book

Volumes are being written on Vietnamese refugee issues’ but very little on the socio-cultural consequences of prolonged refugee detention and the strategies used by the British government in Hong Kong to solve the ‘refugee problem’. Refugees are often understood as a product of forced uprooting, economic changes, ethnic violence, war, famine and natural disasters. There is very little discussion or data on the dynamics of international geo-political considerations in producing and sustaining refugee phenomena. The human misery and the consequences of such a policy is also often overlooked by the refugee administrators and refugee researchers and many human rights and social service agencies. This is essentially because of the policy of the refugee administrators to deny independent access to the camps for researchers and the mass media.

It is generally understood that the process of becoming a refugee involves several stages. Imminent danger or perception of danger, the process of taking a decision to leave, the process of flight, the stage of initial asylum and resettlement or repatriation. Each stage has its own issues, tasks and particular experiences. It appears that the issues and concerns of resettlement and adaptation to the host countries dominate the global literatures on South East Asian refugees. Very little data and experience exists on issues related to initial asylum, particularly about the asylum seekers who are detained for a long time. Such a literature bias is a significant indicator of the nature of global geo-political considerations in academic research and its impact on production of knowledge itself.

This exploratory and descriptive case study of Hong Kong’s experience with the Vietnamese refugees has its implications for theoretical paradigms that have hitherto governed planned intervention for refugees all over the world. The objective of most social service intervention is to assist the asylum seekers to adapt with the local conditions as quickly as...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures, Photos and Tables

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Understanding Refugee Detention: Conceptual and Methodological Issues

- 3 Options and Choices

- 4 Personal Agony: A Commodity in Humanitarian Politics

- 5 The Power of the Host

- 6 The Structure of Powerlessness

- 7 Violence in the Camps

- 8 The Silence of the Power Brokers

- 9 Solving the Refugee Problem or a Planned Ethnocide?

- Bibliography