![]()

1

Introduction

1.1 Background

Despite a growing trend of privatisation in recent decades, of public sector activities remains important in developing and industrial countries.1

A record expansion of the public sector has been observed during the 1960s and 1970s. For instance, in the mid 1970s the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) accounted for 8.6 per cent of GDP (an average of thirty countries) and 7 per cent of overall investment (an average of fifty countries) in developing countries compared to 9.6 per cent and 11 per cent respectively in industrial countries (Gillis et. al. 1983, Nunnenkamp 1987). The share of SOEs in economic activities was relatively higher in developing countries compared to industrial and middle income countries (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Share of the state-owned enterprises in economic activities(Percentage share in GDP)

| Countries * | Weighted Average | Unweighted Average |

| 1978-85 | 1986-91 | 1978-85 | 1986-91 |

| Low-income Countries (18) | 12.4 | 13.4 | 13.7 | 14.2 |

| Middle-income Countries (37) | 9.6 | 10.0 | 8.8 | 9.4 |

| Industrial Countries (10) | 4.5 | 6.0 | 8.2 | 6.6 |

The complex physical, technological and economic nature of infrastructure distinguishes it from other productive activities. Therefore, public provision of infrastructure has traditionally been justified on the grounds of recognition of infrastructure’s economic and political importance. Recent literature has made serious charges against the public provision of infrastructure like serious and widespread misallocation of resources, and failures to respond to user demand (Jones 1991, World Bank 1994). Moreover, it is highly criticised by property right, principal agent and public choice theorists.2 There are other problems such as fiscal drain due to underpricing, subsidising and overstaffing, inefficient spending and inadequate maintenance which are common with public provision of infrastructure. These problems not only reduce the efficiency of infrastructure but also widen the gap between revenue and investment in infrastructure, which in turn adds a burden on the treasury and ultimately on tax payers.

1.2 The origin of public sector in Pakistan

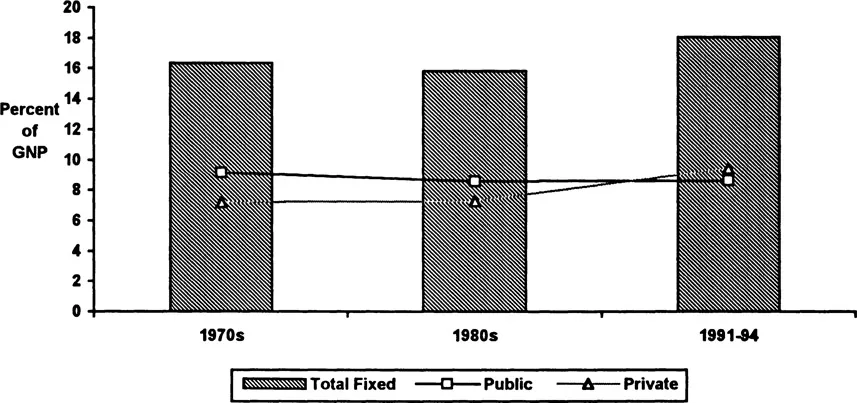

The inadequate manufacturing, finance and infrastructure inherited by Pakistan at the time of independence led to significant changes in the country’s fundamental socio-economic fabric (Vakil 1950). Consequently, the decline of agriculture and the increase in the industrial sector over time altered the role of the public sector from being a ‘gap filler’ to being the ‘engine of growth’ in the 1970s. It was argued that the public sector would not only ensure the desired level of production and distribution of critical goods and services but also would address the inherited imbalance of resources (Mehdi 1987). Consequently, public investment rose significantly compared to private fixed investment during 1970s.3 The situation remained unchanged during the 1980s while in 1991–94 private investment took over the lead in the economic development process of Pakistan. However, a very small increase in the share of total fixed investment in GNP is observed during the period 1971–94, e.g. from 16.37 per cent in the 1970s to 18.05 per cent in 1991–94 (Figure 1.1).

Therefore, the share of the public sector in GDP increased from 9.4 per cent in 1978–85 to 11.4 per cent in 1986–91 (World Bank 1995). Although it is lower than the average for low-income economies and on a par with the average for middle-income economies, it is still high as compared to industrialised economies indicating the significance of the public sector in Pakistan’s economy (Table 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Investment as a percentage of GNP at current price in the private and public sectors

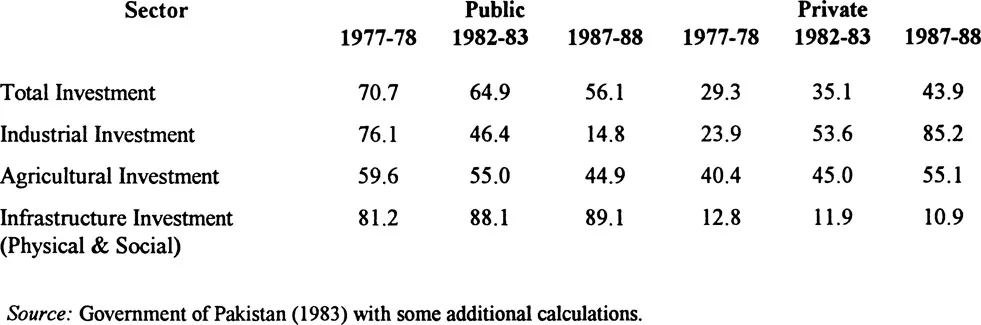

This brief discussion on the role of the public sector in Pakistan’s economy shows that although the total share of private investment in GNP is being increased gradually, the public sector remains critical for many development activities.4 For instance, the government committed itself to provide all infrastructure5 and credit facilities to achieve a healthy and balanced industrial economy at the earlier stage of development. Moreover, the general nationalisation policies during 1972–77 also played an important part in keeping private investor’s away from this field. Later, despite the fact that the private sector was encouraged to provide physical infrastructure, such as construction of highways, airport terminals, energy developments and telephone service in the Sixth Five Years Development Plan (1983–88), the overall percentage share of public investment in the total infrastructure investment increased rather decreased (Table 1.2).

Many factors such as weak private sector, technological complexity, high capital requirements and relatively low profitability in addition to the high risk involved can help to explain this upward trend of the public investment share in infrastructure. Moreover, the objective of cheap and continuous supply of infrastructure facilities for all citizens and the resulting controlled low price policy failed to attract private investor to this field. Above all, political instability and unreliable government policies deterred private sector involvement in infrastructure.

1.3 Definition of state-owned enterprises

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) are defined as independent organisations, corporations, or enterprises which are owned and controlled by the state and produce a marketed output (Kirkpatrick 1984, Rees 1984, Ramanadham 1991). This definition indicates the two central characteristics of SOEs. First, they are independent business organisations and their basic activities are similar to any other firm. But while they are publicly owned, their management is usually accountable to some part of the government apparatus and thus they are open to direct political influence. Second, it is presumed that they should be operated in the general public interest rather than on a profit seeking basis. Therefore, they contain both elements of publicness6 and enterprise. A similar definition of SOEs has been used in this study.

Table 1.2 The shifting role of the public and private sectors

The literature provides various synonyms for state-owned enterprises such as nationalised and public enterprises. Although, the term state-owned enterprise has generally been used in this study, other synonyms have also been used from time to time when and as required by the text to maintain its flow.

1.4 Objectives and scope of the study

The aim of this study is to evaluate the performance of publicly-owned electric power and telecommunications industries in Pakistan in terms of profitability, cost effectiveness and productivity. This study has several objectives.

- The first is to study the overall performance of the two infrastructure sectors, i.e., electric power and telecommunications. The analysis at the firm level is also conducted because two firms, Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) and Karachi Electricity Supply Corporation (KESC) are being operated by the government in electric power sector while only one, Pakistan Telecommunications Corporation (PTC) is responsible for entire sector of telecommunications.

- A second objective is to identify the problems associated with public provision of electric power and telecommunication services.

- A third objective is to present some alternative policy options to reform SOEs.

This study does not attempt to measure the social impact of SOEs, but these issues have been discussed in the text from time to time when and where necessary.

Although this study is based on a quantitative approach, a qualitative analysis has also been used to discuss the alternative policy options in SOE reform. The relative performance of publicly-owned electric power and telecommunications industries in Pakistan has been evaluated in chapter 6, 7 and 8 using a comparison of physical, financial and economic indicators. A Cobb-Douglas production function is also used to calculate the growth rate and trend in productivity to explain the technical efficiency of the firms and the sectors as a whole. Economies of scale are also studied to explain the structure of the industries. Further details of the methodology are presented in chapter 5.

Many developing countries once increased public physical infrastructure significantly but failed to meet the growing demands of businesses, households and other users. Now however, new technological developments coupled with the emergence of global competition and the establishments of global alliances are exposing infrastructure sectors to increased competition. Therefore, many developing count...