![]()

At some stage many of us have discussed amongst friends and colleagues our view of the amount of income we forgo to the government in the form of taxes and the government’s use of these tax collections to fund public works. Typically the discussion results in a unanimous agreement that tax collections are excessive and could be better distributed amongst the various public works that the government has committed itself to providing. As one thing leads to another, tax evasion and avoidance become the topic of attention. If we are particularly unhappy with the government’s handling of the public purse, we may be more supportive of tax evasion and avoidance than we would be if we perceived the government was using public funds in an appropriate and efficient manner. Although these perceptions will turn out to be quite important in determining participation in the ‘underground economy’, it is necessary that we identify, at the outset, the distinction between tax evasion and avoidance. We will argue that tax evasion will form part of the underground economy and tax avoidance will not. Loosely defined, the underground economy may be interpreted as unmeasured economic activity that has contributed to value, as defined by the national accounts, but goes unmeasured by society’s current measurement techniques. The underground economy has been variously described as illicit, cash, irregular, black, shadow, parallel, subterranean, dual, clandestine, gray, moonlight, submerged or hidden activities.

Tax avoidance typically involves a lawful arrangement by the taxpayer to take the necessary steps to minimize their tax obligations by taking advantage of a loophole in the tax system. For example, a taxpayer can reduce their tax obligations by making charitable contributions or by taking full advantage of all taxable deductions. Tax evasion on the other hand is unlawful. It usually involves overstating expenses, claiming expenses that were never made, under-reporting income or simply not reporting income at all. While legal tax avoidance does not distort the quality of the national accounts, tax evasion leads to significant downward bias. If we are interested in improving the quality of the national accounts, we need to have some idea of the extent of tax evasion that is actually taking place in the economy and to take the appropriate steps to do something about it. The principle objective of this book is to provide an estimate of the size of the underground economy (or tax evasion) in Australia and to come to understand the motives that are driving the participation. In this way it may be possible to make some suggestions to help combat, what anecdotal evidence suggests, is a growing underground economy in Australia.

Times may be tough but many ordinary Australians are doing it better than they will admit. By the end of October 1999, some 11.5 million Australians completed their annual tax return, each signing the document to be ‘true and correct’ to the best of their knowledge. Households account for 85% of total taxpayers while companies and partnerships account for 5% and 4% respectively.1 Oddly enough since 1995 some $78 billion has gone unreported annually from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) suggesting many of these income tax returns were in fact misleading. A back-of-an-envelope calculation would suggest that the household sector alone is evading approximately $10 billion in tax liabilities that adds about $1100 annually to the tax liability of the honest taxpayer given current participation in the underground economy.

As a percentage of GDP, the underground economy in Australia has shown strong signs of resilience to government attempts to curb back its size. Measuring on average about 15% of GDP since the mid-to-late 1960s suggests that not only are many ordinary Australians cheating the government from tax revenue, but it appears that the activities have been entrenched in the working ethics over many years. What is even more disturbing is the fact that many of these tax cheats will remain undetected and will continue to lodge misleading tax returns in the future.

Not only are the actions of the tax cheats reducing the size of the tax base and tax revenue, they also affect the quality of economic data which the Australian Bureau of Statistics collects and which policy makers use to gauge their policies. Can we say that the Australian National Accounts (ANA) portray an accurate measure of the activities that are taking place in the economy? Is the inflation rate representative of the prices Australian households are paying for their goods and services? A large underground economy would suggest the answer to each of these questions is no.

If your neighbour, who by trade is a mechanic, offers to repair your car for a price significantly lower than you would otherwise pay, the offer may be too attractive to turn down. Of course, if you accepted the offer, you would be expected to make the payment in cash. Because cash leaves no trail for the tax office to follow, it provides ample opportunity for your neighbour, and others, to evade their tax obligations. In Economics we refer to the outcome as a Pareto Improvement. This means that not only has the mechanic benefited by evading taxes, but you, as the consumer, also benefit from paying a fraction of the price you would otherwise have paid if a legitimate mechanic carried out the repair. Because both parties mutually benefit from the agreement, there is no incentive to report each other to the tax office. However can we say that this is a long-run Pareto Improvement? The answer is probably no because if there are sufficiently large number of agents participating in the underground economy, the impact on tax revenue will most certainly be significant. With commitments and obligations to fund public works, the government may need to increase taxes to compensate for falling revenue. Ultimately the mechanic’s tax break will become your tax burden.

But how does this affect the national account statistics? To better understand this, it is necessary to review what the national accounts are attempting to measure. The ANA measures the economic pulse of the Australian economy and provides the basis for formulating policy that attempts to smooth out business cycle fluctuations. In the ANA, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) estimates the size of economic activity by calculating Gross Domestic Product (GDP). There are three alternative measures by which the ABS calculates GDP:2 (1) the expenditure approach; (2) the income approach; and (3) the production approach. In principle these three methods should yield the same results but in practice they do not. The ABS statistician is required to introduce a ‘Statistical Discrepancy’ item in the ANA in order to reconcile the income side with the expenditure side. The expenditure approach, GDP(E), sums the total expenditures taking place in the economy while the income approach, GDP(I), sums the income derived from the production of the goods and services that make up total GDP. Whenever an underground economic transaction is undertaken both the income measure and the expenditure measures are distorted. Suppose we continue with our mechanic example. If the mechanic fails to declare the money received from repairing your car, GDP(I) is that much lower. On the other hand neither is your expenditure recorded and consequently the GDP(E) is also underestimated. However most underground activities require a combination of labour and physical inputs. The physical inputs are generally purchased in the legitimate economy and recorded in the national accounts. It is the labour services, if they go unreported, that distort the national accounts. The mechanic’s use of spare parts, if purchased from the legitimate economy, would be measured in the national accounts, but the labour service fee, if not reported to the ATO, will not be measured.

Although many underground activities are difficult to detect, the ATO has uncovered a number of individuals and businesses concealing income and evading taxes. However the number of detections are too few compared, to what we will later show, to be a large underground economy. The following are some examples the ATO has uncovered:3

• A small clothing business did not declare cash payments and only recorded cheque payments. When the ATO audited the books of the clothing business, the taxpayer admitted cash was used to pay for private living expenses and wages to employees (who most probably did not declare their income either). The taxpayer received an amended tax assessment;

• A small gardening business kept two sets of books over a four year period - one for cash receipts and the other for cheques. Although only one book was reported for income tax purposes, the two books were kept because the taxpayer had intentions to sell the business. The second set of books was uncovered by the ATO during an audit. The taxpayer received an amended tax assessment for the entire four years and was prosecuted for making false statements to the tax office;

• A large restaurant business was discovered hiding money by ensuring the cash registers would not record the restaurant’s takings for the day. The taxpayer was paying cash wages to the employees. Each employee received a Group Certificate for less than they were actually paid. Neither the business nor the employees declared their actual earnings to the tax office and have consequently received amended tax assessments. Prosecutions are also likely to occur;

• A fruit grower made a private arrangement with their agent for a $1 per carton charge to be invoiced as a special type of delivery charge. The taxpayer would receive from the agent this amount periodically and would pocket the cash. The taxpayer would then use the invoice to claim a tax deduction for the expenses. The taxpayer had their tax assessment amended and received a gaol sentence.

These types of activities are not typical to Australia but occur in many, if not all, countries abroad. In fact the following are some cases that tax offices abroad have detected:

• Japan4 - in 1983 the Japanese National Tax Agency discovered significant tax evasion taking place in the fishing industry. The National Tax Agency discovered that a typically high-income earning fisherman would under-report an average annual salary of a salaried worker. It investigated 243 high-income earners in the fishing industry to find that they had all been cheating. In fact the many luxuries that they owned were beyond their means had they fulfilled their tax obligations. Many of them owned large apartments, yachts, and luxury cars. In another survey of 570 service companies (including software firms) detected 233 of these companies had not declared income to the tax office. On average each of these companies concealed about 75% of that concealed by the average fisherman;

• United States5 - ‘Coyotes’ (men at border points responsible for smuggling immigrants) smuggle people across the United States border and sell them for a steep fee. The immigrants, who typically end up working on farms, usually pay the ‘coyotes’ up front or if they do not have enough money, they pay with their labour. However in more recent years these illegal immigrants began moving into urban areas as the number of raids in rural areas increase. Once these workers find themselves in the cities, they take part in a number of underground activities to earn a living. Because they are not legal residents, they are forced to remain in the underground economy permanently. The tax office and immigration officials have detected many illegal immigrants who either were given residency status because of their circumstances or they were deported back to their country of origin;

• Canada6 - A Canadian pub was discovered, during 1994 to 1997, to have made a number of false expenses in an attempt to reduce its taxable income. The pub owner was claiming a large number of complimentary meals as ‘promotional expenses’ when in fact these meals were being paid for by the patrons in cash. The pub owner was claiming the expenses of providing the meals but concealing the income generated from the sale of these meals. The pub owner has since had his tax assessment adjusted.

There has been much concern recently about the extent of tax evasion and rightly so. After all, the implications are quite serious. First, an underground economy reduces tax revenue that could otherwise be used to fund community services. It also increases the tax burden of the many honest Australians who are complying with their tax obligations. Second, it may encourage honest Australians to participate in the underground economy particularly if they observe tax cheats are constantly eluding the tax authorities of their tax obligations. After all, the benefits are immediate - a larger disposable income and greater opportunities for welfare fraud particularly for those in the lower income brackets.

There appears to be strong anecdotal evidence in Australia to suggest that the underground economy is entrenched in the psyche of many ordinary Australians. It is occasionally typical for a tradesman to offer two prices - one for cash and another for cheque.7 However to be certain of such anecdotal evidence, many academics have produced various methods to measure the extent of tax evasion in their country and abroad. In Chapter Two we identify an appropriate taxonomy for evaluating these illicit activities and in Chapter Three we discuss the various methodologies to measure the underground economy. We will use the term underground economy to mean all types of tax evasion that takes place in the economy and the ‘cash economy’ to represent a sub-set of activities in the underground economy which involve cash specific transactions.

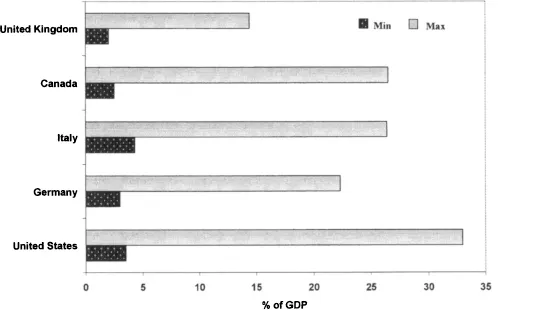

Unfortunately the various names, that are synonymously used when discussing the underground economy, portray different images of the sort of activities that may be taking place. The same term could even mean different things to different people. For example, the term cash economy may either be interpreted to mean only unmeasured legitimate transactions, or it could include criminal activities, such as drug trafficking or prostitution, that are not measured in the national accounts. Consequently the various expressions and interpretations have produced a spectra of estimates for any one country in any given year. For example, in the United States during 1976, the estimates varied between 3.5% (Tanzi, 1983) and 22% (Feige, 1979) of GNP, while estimates for the United Kingdom during 1979, varied between 2% (O’Higgins, 1981) and 14% (Bhattacharyya, 1990) of GNP. For Sweden the estimates for 1978 varied between 3% (Hansson, 1982) and 15% (Frey and Pommerehne, 1984) of GNP, while for Germany, the estimates were just as variable, ranging between 3% (Kirchgassner, 1981), and 16% (Petersen, 1982) of GNP. More recently Karoleff, Mirus and Smith (1993) estimated the size of the underground economy in Canada to be between 15% and 22% of GDP while Statistics Canada believes the underground economy to be much smaller - between 1% and 5% of GDP. In Figure 1.1 we present the various diverging estimates as a percentage of GDP for the period 1976 to 1980. For each country, the various definitions and methodologies (to be discussed below) have produced a wide spectrum of results that, to the casual observer, are quite unconvincing. However, a closer look at each of the methodologies and definitions will serve as the explanation for why the results are what they are.

Figure 1.1 Discrepancies in the Estimates of the Underground Economy Abroad (1976-80)

What is the Underground Economy?

It is no surprise that the lack of uniformity in defining the underground economy has produced so many varied estimates of its size. Unfortunately, even today, there is no uniform definition of the underground economy. Why is this so? The answer may be as simple as it is complicated - simple because some academics are interested in measuring all economic activity, while others are interested only in measuring unreported legitimate activities (activities measured in the national accounts) - and complicated, because the many methodologies used a...