![]()

1 ‘Perfect Information, Perfect Democracy, Perfect Competition’: Politics and the Impact of New ICTs1

RACHEL GIBSON AND STEPHEN WARD

In the space of little more than five years the Internet has gone from being the preserve of computer geeks and academics to being a world-wide media of central concern for political actors and government policy-makers. Even two to three years ago, it would be been rare to have found any mention of the Internet in the tabloid press, now the same newspapers have become Internet Service Providers (ISPs). Barely a day now goes by without the Internet either being declared the solution to a variety of social problems, low political participation and business competitiveness, or being held responsible for the promotion of pornography, racism and violence. Nevertheless, despite its rapid expansion, the majority of the UK population do not yet have access to the Internet; a sizeable minority have declared no interest in using it; and 1.6 million of the British public claim never to have heard of it. Perhaps not surprisingly, speculation about its impact therefore ranges from the wildly utopian to the hugely pessimistic.

This opening chapter seeks to place in context some of these claims by providing an overview of the development of the Internet in the UK and analysing some of the scenarios concerning the potential impact of ICTs at two levels:

• the mass level – centring on public use of Internet for political participation;

• the systemic level – focusing on the potential of the Internet to reform our political institutions and produce new styles of democracy.

What are New ICTs?

The claims for the new media’s transformative effects on our political worlds are premised in the properties that distinguish them from that which came before. Therefore what exactly do we mean when we refer to new ICTs and how are they so different from previous forms?

New ICTs, broadly speaking, constitute forms of digitised information flow, whereby data, be it text, sound or moving real-time images are compressed into a series of zeros and ones and transmitted via airwaves, underground cable and overland networks (Graham, 1998). This technology had its first and most widespread usage in the shape of the Internet, an international network of computers connected to one another that started in the 1960s in the US Defence Department. For a period of over 20 years the Internet remained a largely elite and private mode of telecommunications, used and developed primarily by academics and government bodies (Streck, 1999). Transformation occurred in 1989 with the development of the graphic interface to the Internet, the WWW and the browsers (Mosaic in 1992 and its more sophisticated successor Netscape in 1994). With these developments the Internet became more easily accessible, as did its other applications such as e-mail and use-net. Thus, what emerged was a newer and faster technology that merged telecommunications facilities with mass media publishing.

Given that existing ICTs such as television and the telephone are beginning to move to digital mode and open the possibility of convergence with the Internet, it is becoming more difficult to draw a line around the specific forms of new ICTs. What constitutes the old media and what the new? While this book recognises that an Internet-based media and telecommunications system, accessible via television, may be the next and most influential generation of new ICTs, the focus here is mainly on the existing forms and those most useful for elites, i.e. the Internet, video conferencing and e-mail.

What is Different about New ICTs?

While uniting a number of different applications, new ICTs have generally been distinguished from their predecessors by the following properties (Abramson et al 1988; Bonchek, 1995; Wheeler, 1997):

• they greatly increase the volume and speed of information that can be sent;

• they allow for changes in the style and format of message sent through combining print and electronic communication;

• they decentralise control over the content and timing of messages sent and received;

• they greatly expand interactivity.

On one level, these innovations simply relate to an expansion of the existing capabilities of the old media and telecommunications methods: digital communication speeds up and expands the communication already taking place via analogue television, radio and the telephone. On another more social level, however, they represent a fundamental shift in the mechanism of mass communication. The increases in volume and speed make possible the transfer of far larger amounts of data in a much more immediate way across great geographic distances. In addition, since the development of the WWW in the early 1990s, one can add that new ICTs also innovate in the form of the message sent by combining text-based, audio and visual media into one. As well as overcoming barriers of time and space in information flows, however, this expanded bandwidth also introduces opportunities for much greater user control and decentralisation of media ownership in the communications process.

In the traditional print and electronic media, while there is competition between individual producers of information be they the broadcast networks or newspapers, owing to limited bandwidth or high production costs production of news is centralised in the hands of a few corporate actors. Given the relatively unlimited space accorded to new ICTs such as the Internet, however, and the low cost of production (a computer and an Internet access account), individual consumers can now become publishers of the news, alongside these corporate giants. In addition, as a consumer of news the individual is required to exercise greater initiative in the information-gathering process. Rather than being presented with a pre-packaged edited version in the shape of a daily newspaper delivered through the door or the evening news broadcast on radio and television, the Internet user has to actively search out the information they want. They can then edit and collate their own news sources.

The Impact of ICTs at the Mass Level

At the mass level, new ICTs are seen as presenting significant opportunities and also challenges for expanding public participation in politics. Some argue that the new ICTs, because of the unique features outlined above, will widen the numbers involved in political participation and deepen the quality of that participation. From a rational choice perspective, new ICTs could significantly lower the barriers (costs) to participation for individuals from more marginal and excluded groups. Political activity such as information gathering, joining organisations or directly contacting political institutions and organisations could become far easier and quicker (Street, 1997; Percy-Smith 1995; Mulgan and Adonis, 1994). Further, it is argued that as technological development takes place, access, in terms of the educational and financial resources necessary to engage in the process will diminish. The arrival of set-top boxes and Internet TV will allow the house-bound, such as the elderly, single parents and the disabled, to participate more easily from their homes. The introduction of cheaper computer hardware and Internet connections, along with the introduction of public access in libraries and other public facilities, could help to overcome the exclusion of lower income individuals and families.

The Internet could also deepen citizen involvement by allowing more regular participation and more accountability in political decision-making. Rather than just being able to vote periodically, citizens could be offered considerably more direct opportunities to engage with the political process through electronic referenda, citizen juries, on-line discussion and debate foras with politicians. Engaging in such activities may in itself serve to increase political interest, and stimulate a positive orientation toward participation. Such electronic initiatives, it is argued, will lead to more accountable elites and new communities of interest that in turn will increase the efficacy of participants and encourage further activism (Rheingold, 1995; Rash, 1997).

The contrary and more pessimistic view is that new ICTs will not increase participation, but may well narrow and trivialise it. Critics argue that the optimists have forgotten the financial costs and skills required to use the technology. The costs of going online are likely to remain beyond the poorest in society for some time and simply providing public access points is not equal to having unlimited access at home. Similarly, the socially excluded are also those least likely to have the skills and training to use the technology. Hence, the introduction of new ICTs into the political process could quite easily further strengthen the position of advantage of high socio-economic status (SES) groups within society. In short, the people who already participate the most will gain the most.

Pessimists are equally, sceptical of the ability of electronic forms of participation to produce meaningful political deliberation. They contend that the individualistic push button mode of participation will render participation less meaningful and erode citizen interest, making collective action harder and elites less accountable (Lipow and Seyd, 1996; Street, 1997; Barber et al, 1997). Electronic participation through referenda and the like may become no more than the registering of individual preferences (McLean, 1989). While citizens may have access to large amounts of information on-line, they may either become overloaded and switch off, or not use it and insulate themselves from alternative opinions by only selecting a narrow range of on-line information sources. As Shapiro has noted this raises the possibility ‘that many people may be inclined to use their new power over information to reinforce existing political beliefs rather than to challenge themselves’ (1999, p. 25).

Although it is too early to make definitive judgements about the impact of the technology at a mass level it should be possible to detect some trends towards the digital future. At a minimum, if the optimists are right at least three criteria will need to be fulfilled: rapidly increasing usage so that the Internet is on its way to becoming a mass medium; a narrowing of reduced SES usage differences; indications that the mass public are using/are interested in using the WWW for political purposes.

The Growth of the Internet: Towards a Mass Medium?

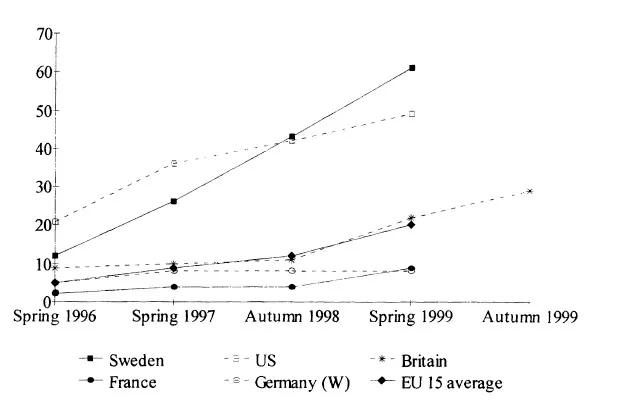

Internet usage rates in the UK have increased markedly since 1994 but the pattern of growth has been somewhat distorted (Figure 1). In the early years it grew relatively slowly by only 1 or 2 per cent per year. However, since autumn 1998 there has been a rapid uptake of Internet technology. The numbers claiming to use the Internet regularly have doubled in the space of six months from 11 percent in autumn 1998 to 22 percent by spring 1999. At the time of writing (late 1999), latest indications show that this has risen sharply again, to just under 30 per cent of the population, with overall potential access to the net rising to around 40 per cent of the UK population. If one adds on those with access to e-mail only, then some 60 per cent have the potential to use e-mail and/or the WWW according to Cabinet Office statistics.

If such access and usage figures are compared with other similar countries, then the UK is in the top quarter. However, it is well behind Scandinavian countries (Sweden was first European country where Internet penetration exceeded 50 per cent of the population in 1999) and the USA, but has favourable usage rates compared to Germany or France. As a result, it has been argued that the growth of the Internet in the UK resembles a somewhat similar pattern to that in the USA, but with the UK lagging around two years behind the USA in terms of Internet coverage.

Figure 1.1 Internet Users (percentage of population)

Source: Adapted from Norris, 1999, p. 20

The best explanation for the sudden surge of growth was the introduction of ‘Freeserve’ by the Dixons retail group, which provided a no-charge service for connecting to the Internet and the resulting growth of competing ISPs. Within weeks of Freeserve being introduced 900,000 people had signed up.2 By spring 1999 nearly all major ISPs had scrapped subscription and joining charges for Internet and e-mail use and a wide range of organisations including banks, supermarkets and newspapers were all offering Internet access. Nevertheless, the bare user statistics need to be treated with caution on a number of grounds. First, regular usage is often only defined as using the Internet in the last month. Daily users of the WWW comprise a much lower figure of around 10–15 per cent of the UK public. Second, there is a gap between access to the Net and actual usage of it. For example, it has been reported that although people are often given free introductory access when they purchase new computers, many fail to make use of it, or use it only for e-mail rather than surfing the Web.3 Third, even though the costs of technology are falling in real terms, there is still a considerable barrier of the high costs of UK telephone calls for using the Internet. Repeated surveys have shown that people are reluctant to go on-line given the costs of calls and that even when they do, they are conscious of limiting their browsing time. Recent estimates indicate that British users spend only 17 minutes a day on-line, only one quarter that of their American counterparts.4

User Profiles

In terms of the profile of users, from the limited evidence available it appears that the UK follows the stereotypical pattern identified in more numerous American studies. Heavy Internet users tend to be predominantly male, middle class, in professional employment, with high educational attainment (degree standard and above) between the ages of 24–40 years old, residing in urban areas. In both the USA and Europe the work of Norris (1998; 1999; 2000) and Bimber (1998) over a three-year period (1995–1998), indicates that those accessing the Internet and using it for political purposes (either information seeking or contacting and discussion) had higher levels of political interest, knowledge, efficacy and were of higher socio-economic status (see also Chapter 10). Similarly, in the European context Gibson and Ward identified the key variable determining on-line political activity was one’s pre-existing proclivity to engage in political debate off-line. Consequently, it was concluded that:

The Internet is not galvanising hordes of previously apathetic individuals to become more politically involved; neither is it promoting a deepening divide between information rich and poor… . Indeed, if anything, it may lead to a deepening of political involvement as new modes of participation open up (Gibson and Ward 1999a, p.17).

Nevertheless, important caveats have been offered in relation to these general trends that may provide hope for supposedly democratising potential of new ICTs. First, the greater proportion of younger users (18–29 year olds) relying on the Net for news. Such a trend could lead to greater political involvement amongst this traditionally disinterested group. Second, in the USA at least, Bimber (1998) detected that general levels of civic engagement and propensity to vote actually increased among those with Internet access, regardless of SES. Third, as many of the surveys point out, uneven profiles may level out over time as access increases. As a result, some of these demographic imbalances may be relatively short lived, others more enduring. Although income and class disparities appear as yet stubbornly ingrained, evidence is already emerging that the gender and age distinctions are being eroded. More women and older people have moved on-line since 1998 and surveys are now showing that the number of women on-line in the UK is nearing 40 per cent.5

Although overall usage of the Net is growing, political activity on-line remains a minority interest. The Internet is currently reliant on citizens actively seeking out and visiting sites. Simply because (political) sites are available does not mean that they will be used. Independent evidence indicates that most people do not go on-line for politics and are relatively conservative in their choice of sites. Sport, sex and shopping remain the commonest areas of interest on the WWW. Perhaps even mo...