- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Heterodox Views of Finance and Cycles in the Spanish Economy

About this book

This title was first published in 2002: Why do endogenous cycles persist in Spain? Manuel Roman demonstrates a highly novel approach to the study of finance and the persistence of endogenous growth cycles, providing a balanced account of the Post Keynesian, Classical and Neo-classical political economy approaches. Finding key propositions from a representative set of heterodox cycles' models, he rigorously tests their chief claims, grounding his research in empirical data. The endogenous forces behind persistent fluctuations in the Spanish economy are also identified and explored in this theoretically rich text, the first of its kind to examine the Spanish economy in such great detail.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Heterodox Views of Finance and Cycles in the Spanish Economy by Manuel Roman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

The central object of my investigation concerns the role of finance in economic growth and its link with the persistence of business cycles in Spain. It is my contention that the roots of what are now considered heterodox views of these matters can be traced to the dynamical approach pioneered by Classical Political Economy. A case study of this kind provides invaluable testing grounds to assess the relevance of some accepted conventions found in contemporary theories of growth and cycles. In particular I will stress the fact that that some of the stylized facts found in this literature are not present in the Spanish case, for example the capital-output ratio was not constant at all but rather rose sharply from the early 1960s through the early 1980s and less rapidly thereafter. After a sharp fall in the mid-1970s, the share of profits trended upwards from the early 1980s through the present. Despite the crucial role of bank credit to prop up standing firms in the depression phase (from the mid-1970s through the early 1980s) evidence that the share of internal funds to finance business investment increased is strong. This is why I believe that the Spanish experience provides support for my understanding of the Classical approach.

After presenting two succinct views of what constitutes the Classical approach from a heterodox perspective, I will outline my own version derived from Lowe's synthesis (Lowe, 1954) and will then proceed to link up the main thrust of these interpretations with the central tendencies of the Spanish economy. Then I will lay out the contrasting views of the monetarist and Post-Keynesian traditions regarding the role of money and credit in business activity. I will conclude outlining a theory of inflation elaborated by A. Shaikh as an extension of his model of finance, accumulation and cycles. I will show its connection with the Classical approach and finally its empirical strength applied to the Spanish case.

The classical approach

The Classical Economists took growth for granted as long as structural barriers did not hamper the extraction of the economic surplus from productive employment. The consumption of workers in this pursuit was a cost of production to capitalist firms advancing circulating capital. Capitalist consumption of goods or the services of unproductive labor was viewed as a subtraction from business savings. Internal finance was sufficient to sustain capital accumulation and no stimulus from government deficits or bank lending was essential for its growth.

Abstracting from the differences in the works of Smith, Ricardo, Malthus and Marx, Classical growth models according to Donald J. Harris share as a basic assumption:

recognition that accumulation and productive investment of a part of the social product is the main driving force behind economic growth and that under Capitalism, this takes the form mainly of the reinvestment of profits (Harris, 1987, p. 445).

Kaidor's understanding of the characteristic features of the Classical approach also brings out the primacy of profits:

profits were assumed to be largely saved and invested, whilst wages are consumed, the share of profits in income also determines the share of investment in total production, and the rate of accumulation (Kaldor, 1965, p. 180).

Adam Smith saw technical change fostering the division of labor, raising labor productivity and expanding both employment and the surplus since population expansion would in due course put a lid on the growth of wage rates. Higher productivity leading to expanding profits would promote higher accumulation and a growing demand for labor, but wage rates would only rise temporarily because if wages went up, net birth rates would increase and population growth would surpass the labor demand.

Ricardo brought out the link between accumulation and the class distribution of income. He examined how structural changes in the class distribution of the surplus between productive capitalists and landowners could slow down or even bring to a halt accumulation altogether. Initially accepting Smith's view of growing employment with rising accumulation, Ricardo saw the secular rise in wage rates coming about as a result of expanding accumulation. As cultivations bumped against the boundaries of the best soil for growing food, capitalist farmers would be forced to cultivate progressively lower grade areas. The rising cost of food at the margins would push wage rates higher, thus allowing the landowners of the better lands to capture an increasing share of the surplus in the guise of differential rents. Ricardo then argued that if the surplus retained by capitalists declined, so would accumulation. Finally in contrast to Smith, Ricardo also allowed that labor saving technical change and declining accumulation would reduce the demand for labor, harming employment.

Malthus on the other hand questioned the viability of exuberant accumulation in the absence of external sources of effective demand. If workers consumption demand was limited by subsistence wages and capitalist consumption was constraint by competition and the drive to accumulate, where would the final demand for the growing output to be found? This question led Malthus to theorize the necessity of cycles as an organic feature of secular growth. For Malthus the accumulation drive would widen the gap between the growing capacity to produce commodities and the insufficient growth of final consumption demand. Hence periodic slumps would punctuate this growing imbalance and their destructive force would temporarily reduce the existing gap.

Malthus then was instrumental in laying the grounds for the modern Keynesian theories of effective demand, growth and cycles. Classical economists including Malthus and Marx were aware of the fact that unexpected shocks occurred periodically, giving rise to market turbulence that accentuated the systemic imbalances out of which central tendencies emerged. Neo-Classical economics on the other hand treats shocks as perturbations of an otherwise balanced growth path.

The Spanish economy and the classical approach

I think that this is not only a fair view of the Classical approach to the determinants of accumulation, but also captures the actual central tendencies behind the structural changes in Spanish growth. The fundamental dynamics of growth underlying the Classical school were discernible in Spain, particularly if the boundaries of that school are extended to include Marx's analysis of the effect of technical progress on profitability via the rising capital-output ratio. Then the relevance of the Classical approach linking the evolution of profits and accumulation is decisive.

The Spanish economy traversed through a decade of development in the 1960s, followed by a period of depression lasting from 1975 through the early 1980s, a faltering recovery ending in the 1993 slump and a new cyclical upturn ending the century. Despite these sharply contrasting phases of its development, some structural features common to all stand out distinctively. My reading of the turbulent experience in Spain suggests a definite answer to some basic theoretical questions.

In this light, a basic question underlies all others, was economic growth endogenous, once capitalism was in full sway? Despite the financial support rendered by a variety of external sources at different stages of development, I will argue that the evolution of profits set the central tendency for the changes in the rate of accumulation.

Related to this question, was economic growth linear along a balanced path, or rather, were cycles endogenous to growth? An examination of the systemic changes brought about by technological progress, such as the rise in capital-output ratios for over twenty years of development, point to a nonlinear growth path running trough sharp fluctuations in accumulation growth rates.

Was there a "knife-edge" corridor evident in the growth experience of the Spanish economy? If growth took place through cycles, were there attractors that kept the fluctuations within bounds, in other words, was the growth path stable? The answer to this question is complicated by the onset of depression from the mid-1970s through the early 1980s. I would argue that intractable systemic forces caused the slump, namely the impact of rising mechanization on capital-output ratios and its effect on profitability, Attractors were present, nevertheless. As accumulation plunged and unemployment soared structural changes were underway depressing the share of wages and raising that of profits. Phases of rapid growth after the early 1980s on the other hand expanded employment and reversed the growth of the profit share somewhat, although the overall trend was never altered.

During the years of depression large infusions of credit salvaged the integrity of the businesses that remained standing. Once the banking system came to the rescue, did credit contribute to lift the path of accumulation or did it merely have a temporary boost that dissipated as the accumulated debt was repaid with funds that were no longer available to finance investment? Accumulation was negatively impacted by the stagnation of profits in the 1970s and positively affected by its recovery in the late 1980s, but the accumulation path remained distinctly lower than it was in the 1970s.

In my view then the rise, stagnation and recovery of the profits mass, the residual after subtracting wages and depreciation from the business sector GDP, was the key force shaping the trajectory of the accumulation path in Spain for the past half-century. After the 1980s, business savings increased as the trend in the share of profits and that of retained earnings relative to profits went up. Indeed running through the contrasting phases of growth, depression and recovery in Spain, the relentless pursuit of structural changes favorable to the expansion of profits gained momentum.

I will endeavor to show, moreover, that questions previously excluded from the Classical approach to development, such as the role of credit in capital accumulation and its effect on short-term fluctuations, can be answered without abandoning the basic principles of that paradigm.

The long-run growth trend

Business practice alone should suffice to shed light on the significance of profits for capital accumulation and output growth. We would expect that because the pursuit of profits by business enterprise is paramount, the growth of output must be closely related to the dynamics of the profit rate. From the Keynesian perspective the derivation of this conclusion follows from the equilibrium condition for income determination. Assume that government expenditures, G equal taxes, T. The equilibrium level of income requires that I = S = s∏. Further assume that all savings, S is a portions of actual profits, ∏. Now define normal profits, , that is actual profits divided by capacity utilization, u. Then actual profits are equal to normal profits only when capacity utilization, u equals 1. The equilibrium condition accordingly becomes: I = s∏ = s u ∏n. Expressing this equality relative to the capital stock, K we have:

This key expression says that the growth rate of fixed capital is a function of the propensity to save (out of profits) and the profit rate and only when u = 1, will the growth rate, gk = srn. In Spain as profits grew larger, capital investment growth rates rose from the mid-1950s through the early 1970s. Falling profitability after the mid-1960s, however, had a dampening effect on the growth of accumulation. After the early 1970s the growth rate of fixed capital investment could no longer compensate for the decline in profitability and the mass of profits stagnated. The collapse of profits after the mid-1970s dragged output growth rates down as the rewards of accumulation practically vanished. The neat historical record of their growth and collapse leaves no doubt concerning the non-linear nature of the system's growth path.

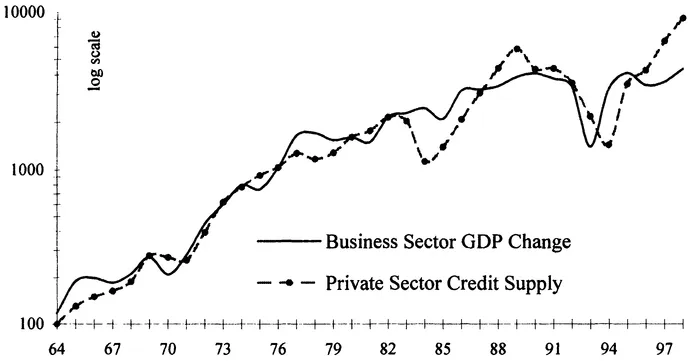

My chief concern here centers on the dynamics of short-term GDP fluctuations and its relation to credit cycles in bank lending to finance excess demand by business and government. My view is that these cycles occurred around a trend set by the long-wave dynamics of the profits mass. Examination of the growth path of the Spanish economy after the mid-1960s reveals the presence of persistent short-term fluctuations. I believe the marshaled evidence will confirm the presumption that these cyclical movements were connected with matching cycles in short-term credit growth. As long ago as the 1930s, however, John Strachey found it necessary to remind his Keynesian readers that the existence of credit did not imply the absence of a budget constraint. While seeking to explain the genesis of the deep depression then engulfing the world economies, he indulged his fancy in a playful exercise comparing a "creditless" economy with one in which external finance was available:

If we can imagine a creditless capitalism in which every transaction was mediated by hard cash, then it is true that the oscillatory form of the crisis, but not the crisis itself might be abolished. We should get a slow, steady decline of the rate of profit which would act upon the system like a creeping paralysis (Strachey, 1935, p. 313).

Figure 1.1 shows the simple correlation between the nominal business-sector GDP yearly change and the private sector yearly credit supply change in log scale. The yearly credit supply is the average of the monthly credit supply. Both start in 1964 because reliable data for credit growth before that date is not available. I do not believe that these GDP fluctuations were caused by the vagaries of an exogenous supply of credit-money. On the contrary, the state of current business profitability combined with expectations of future sales motivated the demand for and provision of credit. In my view, the supply of credit-money is fundamentally endogenous to the needs of business for short-term working capital.

Figure 1.1 Yearly GDP and credit supply change

Sources: Series 832000 and 970000T.

Sources: Series 832000 and 970000T.

My concern with the role of credit in the formation of growth cycles cannot overlook the underlying forces shaping the long-term behavior of accumulation. In this regard the marginal profit rate, defined as the change in profits between two consecutive years relative to investment spending with one-year lag, proved to be a good harbinger of investment growth. The dynamics of profitability set the non-linear growth path for the economy. Its driving force from the early 1960s to the early 1980s was the remarkable technical revolution that radically transformed the composition of the capital stock. The mechanization of production led to a rising capital-output ratio that dragged profitability way down from its initially lofty levels. In addition to technical change shaping the trend, after 1970 empirical evidence supports the existence of two medium-term growth cycles akin to Richard Goodwin's theoretical constructs. Goodwin's growth cycles reflect the effect on accumulation of changes in the wage-share, abstracting from credit and finance except in so far as they affect profitability. My findings show that after the late 1960s medium-term changes of the wage share punctuated the long-run trend in profitability and modulated its downward bent.

External finance and accumulation

Because I relied so heavily on the perspective found in Classical Political Economy regardi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- PART I: HETERODOX GROWTH AND CYCLES MODELS

- PART II: OVERVIEW OF THE SPANISH ECONOMY

- PART III: EVALUATING THE MODELS

- Bibliography

- Index