- 476 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Vietnam War

About this book

The Vietnam War remains one of the most contentious events in American history. This book is a collection of essays that seeks to examine the current state of scholarship on the war and its aftermath. It is divided into five sections which address American presidents and the war, the conduct of the war in the field, the impact of the Tet Offensive, the meaning of the war and its lasting legacies. The purpose of the collection is to present the most recent contributions to the continuing academic and scholarly dialogue about one of the most momentous historical events of the twentieth century.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

US Presidents and the Vietnam War

[1]

What Did Eisenhower Tell Kennedy about Indochina? The Politics of Misperception

Fred I. Greenstein is professor of politics at Princeton University. Richard H. Immerman is professor of history at Temple University. The authors are indebted to a number of commentators on earlier drafts of this paper, including McGeorge Bundy, Michael W. Doyle, Alexander L. George, Robert Jervis, Russell Nieli, and editor David Thelen and the five referees for the Journal of American History: Stephen Ambrose, Lloyd Gardner, Mark Leff, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., and Michael Sherry. Professor Greenstein is indebted for research support to the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation and to the John J. Sherrerd and Oliver Langenberg Funds of the Center of International Studies, Princeton University.

Events so momentous in their consequences that they seem after the fact to have been the result of unalterable historical forces sometimes prove to have roots in decisions that appear to have been far from inevitable at the time they were made. A case in point is the transformation of the United States advisory role in Vietnam to a full-scale military intervention in the 1960s. On July 28, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced what in effect was an open-ended commitment to use American military force to defend South Vietnam. He justified his actions in terms that implied that he had little choice but to act as he had, stating that “three Presidents—President Eisenhower, President Kennedy and your present President—over eleven years have committed themselves and promised to defend this small and valiant nation.” Yet Johnson’s announcement came after six months in which he had authorized a series of incremental increases in the American military presence in Vietnam, doing so in a context in which there was nothing approaching consensus on the part of his advisers or of others in public life about what, if anything, the United States should do to keep South Vietnam from falling to the Communists.1

If American leaders were undecided about Vietnam in 1965, they were even more so before then, in spite of Johnson’s attempt to portray agreement on the part of his predecessors. The lack of such a consensus became painfully evident to Johnson and his associates shortly after his July 28 announcement when one of the presidents who had ostensibly pledged the United States to defend South Vietnam, Dwight D. Eisenhower, denied that he had done so.2 The discrepancy between Johnson’s impression of what Eisenhower had obligated the United States to do and Eisenhower’s own view of the matter produced a minor political storm in 1965, which might be of little interest today were it not that it has implications for a variety of larger issues bearing on the nature of political communication, the organization of national security decision making, the methodology of historical inquiry, and the perennial question of whether and to what extent the Vietnam War was a necessary consequence of the political convictions of American decision makers and the real or perceived circumstances they faced.

In what follows we explore Eisenhower’s stance on American military intervention in Southeast Asia in the period before the Johnson administration transformed the United States advisory presence in Vietnam into a military intervention. We do so with particular attention to a fascinating episode in which Eisenhower, on the last day of his presidency, met with his Democratic successor and several of his own and John F. Kennedy’s advisers in a Rashomonesque meeting from which participants emerged with diametrically opposed interpretations of what Eisenhower had said. We frame our account with a summary of the controversy in the summer of 1965 about whether President Eisenhower had committed the United States to defend South Vietnam, and then we discuss the meeting in question and the reasons for its blind-men-and-the-elephant character. We conclude by reflecting on the larger implications of the episode, particularly those that bear on the question of whether the convictions of American decision makers in the period before the United States became a party to the war in Vietnam made American intervention inevitable.

The 1965 Controversy about Eisenhower’s Commitment

Eisenhower’s denial that he had committed the United States to defend South Vietnam came in a news conference on August 17, 1965. The still-popular former president, who commanded particular respect on national security matters, declared that while he agreed with Johnson’s objectives, he had not guaranteed American military support to Vietnam. Under the current circumstances, he acknowledged that “the Communists must be stopped in Vietnam,” but in the 1950s we “were not talking about military programs but foreign aid. There was no commitment given in a military context except as part of SEATO” (the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization).3

The Johnson administration moved rapidly to control any damage that Eisenhower’s remarks might have caused. The next day White House press secretary Bill Moyers stated that Johnson did “not feel that there is any difference with General Eisenhower.” The president, Moyers explained further, “thinks the purposes of the Johnson Administration are the same as those of the Eisenhower Administration—to preserve peace and in doing it, present to the world the face of unity, a policy of harmony.” On August 19, Eisenhower called another news conference, declaring his support of the president and pointing to “how different the circumstances are today from a decade ago.” At that time he had hoped that North Vietnam would refrain from military aggression and that economic assistance to the Saigon government would be sufficient. That hope, he lamented, had not been realized.4

Notwithstanding the statements by Moyers and Eisenhower, the controversy lingered. On August 23 the White House issued a pamphlet, “Why Vietnam?” But before distributing it, Johnson, using Gen. Andrew J. Goodpaster as liaison, asked Eisenhower to review the pamphlet’s history of the evolution of the United States commitment to South Vietnam. Eisenhower saw nothing in it to take issue with. The House Republican Committee on Planning and Research nonetheless published a “white paper” assailing Johnson’s actions in Vietnam by distinguishing them from Eisenhower’s.5

The White House initiated a spate of actions designed to substantiate the claim that Johnson was continuing the policy of his predecessors. Some of this effort went into canvassing the record for official guarantees made by Eisenhower to South Vietnam. The nearest thing to a guarantee, however, was Eisenhower’s October 1954 letter to Premier Ngo Dinh Diem stating that the United States would assist South Vietnam in “developing and maintaining a strong, viable state, capable of resisting attempted subversion or aggression through military means.” But this pledge of assistance contained important qualifications: South Vietnam was indeed only being offered foreign aid, and even that was contingent on “performance on the part of the government of Vietnam in undertaking needed reforms.”6

Taking another tack, Johnson’s staff searched for documentary evidence of what had transpired at a meeting in which they had reason to believe Eisenhower had stated his conviction that the United States should use military force to prevent a Communist victory in Indochina. Johnson’s assistant for national security, McGeorge Bundy, conducted the search. The meeting in question, which took place on January 19, 1961, the final day of Eisenhower’s presidency, was between Eisenhower, his successor, John F. Kennedy, and the president-elect’s top national security aides. High on the agenda was the situation in Indochina, particularly in Laos, the Indochinese state that at the time appeared to be most threatened with an imminent Communist takeover.

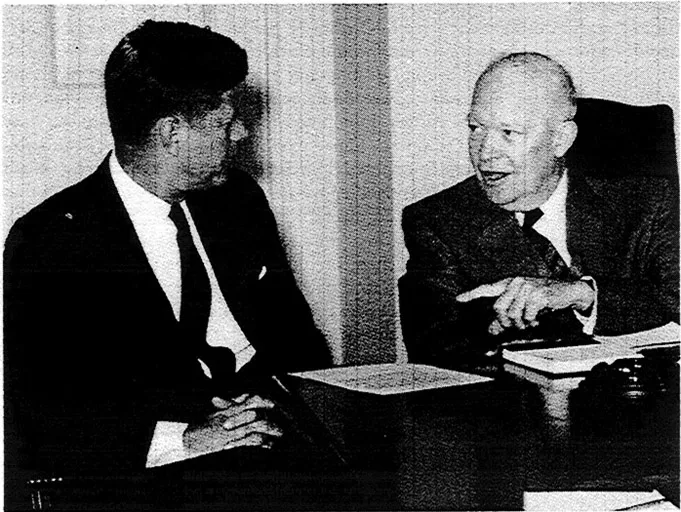

President Dwight D. Eisenhower and President-Elect John F. Kennedy at their January 19, 1961, meeting. This photograph, which appeared on the front page of the New York Times, accompanied a story about preparations for Kennedy’s inauguration.

Courtesy AP/Wide World Photos.

Johnson’s secretary of state, Dean Rusk, who had attended the meeting as Kennedy’s secretary of state–designate, recollected that Eisenhower had advised Kennedy to take unilateral military action in Laos if that were the only alternative to losing that nation to the Communists. The logical inference was that while Eisenhower might not have made any formal commitments, he clearly had viewed it to be in the national interest to defend Indochinese states that seemed about to succumb to the Communists. This, of course, would apply to the Indochinese state in danger of falling to the Communists in 1965—Vietnam.7

Rusk’s recollection of the meeting in question jibes with what historians have long held Eisenhower’s advice to have been. The prime sources of this understanding were the two “court histories” of the Kennedy presidency that were published shortly after Kennedy’s death—Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.’s A Thousand Days and Theodore C. Sorensen’s Kennedy, both of which were published in 1965. The first in fact had been serialized in Life magazine in the weeks just before Johnson’s aides sought to establish what advice Eisenhower had given Kennedy about Indochina.8 According to Schlesinger, Eisenhower told Kennedy that Laos was “the key to all Southeast Asia,” and that he hoped that SEATO would take action to prevent a Communist takeover. He doubted, however, that the French and the British would permit this to occur. Schlesinger reports that Eisenhower went on to say that a Communist victory in Laos would place “unbelievable pressure” on Thailand, Cambodia, and South Vietnam, adding “with solemnity” that Laos “was so important that, if it reached the point where we could not persuade others to act with us, then he would be willing, ‘as a last desperate hope, to intervene unilaterally.’” Sorensen quotes Eisenhower to the same effect, asserting that the outgoing president described Laos as “the most immediately dangerous ‘mess’ he was passing on” and warned that “’You might have to go in there and fight it out.”’9

The failure of Johnson and his associates to make public the results of their investigation suggests that their quest for convincing evidence was to no avail. To see why this was so, we need to consider the evidence they did turn up and how they responded to it. That evidence proves to be part of a much larger and fascinatingly contradictory documentary record on the January 1961 Eisenhower-Kennedy meeting, a record that has been declassified in recent years at the Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson presidential libraries.

The Documentary Record

The January 19, 1961, meeting was convened to discuss a number of pending political issues, the most pressing of which was the situation in Laos. Eisenhower and Kennedy were accompanied by Secretary of State Christian A. Herter, Secretary of Defense Thomas S. Gates, Jr., Secretary of the Treasury Robert B. Anderson, and their counterparts for the incoming Kennedy administration—Dean Rusk, Robert S. McNamara, and C. Douglas Dillon. Each of the principals also brought a staff aide to the meeting: White House chief of staff Gen. Wilton B. Persons, in Eisenhower’s case, and Washington attorney Clark M. Clifford, in Kennedy’s.

Four of the participants prepared records of what had transpired. That of Clark Clifford, the president-elect’s liaison with Eisenhower for the transition, proves to have bee...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- PART I US PRESIDENTS AND THE VIETNAM WAR

- PART II PROSECUTION OF THE WAR

- PART III TET AND KHE SANH

- PART IV LOOKING BACK ON THE VIETNAM WAR

- PART V LEGACIES OF THE VIETNAM WAR

- Name Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Vietnam War by James H. Willbanks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Vietnam War. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.