![]()

1

The approach: an overview

Introduction

In this chapter we set out our approach in general terms. We introduce the reader to a number of ideas which will be more fully developed in later chapters. Our intention here is merely to give the reader a provisional working framework within which to fit particular ideas as they come up. We begin by asking exactly what is going on when a person is reading. We suggest that as you read you predict meanings and check against textual cues whether they are correct or not. A sort of conversation goes on with yourself though you are probably not aware of it. The ‘conversation’ is mostly concerned with the meaning of the text, i.e. with what we call ‘product’ or ‘content’. What is needed, we argue, is to develop techniques for having a ‘conversation’ about process, about the ways you read. We then go on to sketch a preliminary language for that conversation by suggesting that we talk about reading in terms of purpose, strategy, outcome and review.

What is going on when a person is reading something?

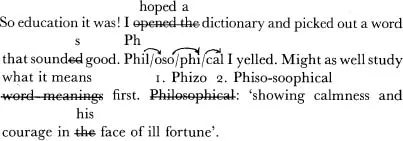

Opinions differ, but one view which we find attractive has been gaining ground in recent years. This sees reading as essentially a continuing series of predictions about the text. Here, for instance, is a record of a relatively proficient young reader reading a passage aloud. A stroke through a word with a word written in above indicates a mispronunciation or substitution. A curved arrow indicates a repetition:

We see that in the second sentence the reader substituted ‘hoped’ for ‘opened’ and ‘a’ for ‘the’; and he had to have several tries at the word ‘philosophical’ in the third sentence, repeating it syllable by syllable. What is interesting is that the substitutions are nearly all perfectly sensible ones; they accord, that is, with what the reader could expect the next word to be having read so far. In the fourth sentence, for example, it looks as if the child registered the ‘w’ of the word after ‘study’ and then guessed ahead to what followed. Actually, the guess was quite a good one. ‘What it means’ fits in perfectly well with the sense. To take another example: in the second sentence it looks as if the child correctly identified the word ‘sound’ but predicted the ending wrongly. ‘Sounds’ would, however, have been correct grammatically and would also have made sense.

Since the predictions are not random but fit in with the requirements of sense and grammar it seems likely that they are made as part of a pattern of continuing response to cues in the text. Cues encountered after prediction help the reader to check whether the prediction was correct. In the second sentence, for instance, it might be that the reader responded to the ‘o’ sign in ‘opened’ but predicted – wrongly – the word ‘hoped’. When he had read a little further he saw that ‘hoped’ would not do; it would not fit in with the rest of the sentence. Accordingly, he abandoned the prediction, went back and made another, correct, one.

It seems that as the reader reads he or she is predicting meanings that will be symbolised by the words on the page. The reader’s eyes scan the words to discover whether they are compatible with his or her expectations. This scanning process continues evenly unless the reader’s expectations are not met. If that happens the process falters. A mismatch occurs between expectation and meaning. Such a mismatch can occur for many reasons. The reader may have predicted wrongly the meaning of a single word or phrase, or perhaps the whole drift of his expectation is wrong. What then happens is that he has to search the text more carefully for cues which will help him to find the right meaning. He then returns to the high-speed scanning which characterises the normal flow of reading.

Obviously this is a very curtailed and over-simplified description of a highly complex process. The example was taken from an article by Goodman and the reader may wish to refer to his writings for a more detailed account. There are other views of the reading process but the predictive model which we develop later in the chapter seems to us especially helpful for thinking about the reading behaviour of experienced readers, of undergraduates or students taking A level, whose reading skills are already well advanced.

For one thing, the process of prediction, of attributing meaning to the marks on the page, depends to a great extent on the use the reader is able to make of context, both the context provided by the text and the wider context provided by the reader’s own experience, knowledge, interests and purposes. An experienced reader brings a great deal to the act of reading. Such a reader has, indeed, a considerable advantage over younger, less experienced readers, and an approach to reading which starts from that fact is likely to prove particularly fruitful for present purposes.

Another feature of the approach which attracts us is that it does not present reading as a passive process of deriving meaning from the text. Instead, it sees the reader as constantly taking initiatives, as continually proposing meanings to the text. We shall argue that it is this reader initiative which opens up the possibility of improving one’s reading ability. If one can nurture the process of reader initiative then one can operate consciously upon one’s reading patterns. The first thing we need to do, then, is to become more aware of ourselves as readers.

Reading self-awareness

If we ask someone about the way they read they will not reply, of course, in terms anything like those we have put forward above. Usually people volunteer statements like the following:

I read word by word.

I read from the beginning to the end.

I can read all right, but I cannot remember afterwards what I’ve just read.

I can’t concentrate for long. My mind wanders.

Surprisingly often replies reveal personal superstitions about reading:

I need to smoke.

I must be alone.

I must have the radio on.

Such knowledge is at the level of sympathetic magic. Even when the replies are more to the point there is usually very little awareness of their implications.

I always read the same way.

I make different sense from an article if I read it again.

I read the important bits usually.

People’s knowledge of the way they read tends to be fragmented. They have several bits of information but they do not know how to bring the bits together into a coherent explanation. They lack, in our terminology, the tools for a satisfactory conversation about reading.

The reading conversations

Goodman describes reading as a kind of ‘psycholinguistic guessing game’. Efficient reading, in his view, results from skill in selecting the fewest and most productive cues necessary to produce guesses which are right first time. We prefer to think of reading as a kind of conversation between the reader and the text. The reader puts questions, as it were, to the text and gets answers (what we have called ‘cues’). In the light of these he puts further questions, and so on.

For most of the time this ‘conversation’ is inaudible. It goes on below the level of consciousness. At times, however, we become aware of it. This is usually when we are running into difficulties, when mismatch is occurring between expectations and meaning. We sometimes catch ourselves saying to ourselves things like ‘What on earth is he talking about?’, ‘Where have I got to?’, ‘Hallo, I’ve missed something’ or ‘I’m completely lost. I shall have to go back and start again’. It is then that the conversation becomes audible. Significantly, it is when mismatch is occurring. When successful matching is being experienced our interrogation of the text continues at the unconscious level. There is no need to bring the process into the foreground of our consciousness.

Different people converse with the text differently. Some stay very close to the words on the page; others take off imaginatively from the words, interpreting, criticising, analysing and extrapolating. The former represents a kind of comprehension which is ‘literal’ (i.e. as written in the text). The latter represents higher levels of comprehension (i.e. as interpreted by the reader). Actually, the reader is always doing both to some extent. You cannot take off imaginatively unless you have first understood the words at some kind of literal level. However, we have found in practice that people often tend to one extreme or the other. They are either over-conformist as readers (and don’t take off critically enough) or undisciplined as readers (and don’t pay sufficient regard to what the text actually contains). The balance between these is important, especially for advanced readers. The kind of reading required in further or higher education places considerable emphasis on both.

The conversation that we have been so far concerned with has been to do with meaning, with the content of the text. But there is another kind of conversation which from our point of view is equally important, and that is to do not with what is read but with how it is read. We call this a ‘process’ conversation as opposed to a ‘content’ conversation. It is concerned not with meaning but with the mechanics of our reading, with the strategies we employ and with appraisal of their effectiveness. If we are an advanced reader our ability to hold a content conversation with a text is usually pretty well developed. Not so our ability to hold a process conversation. It is precisely this kind of conversation that is at issue when we are seeking to develop our reading ability to meet the new demands being placed upon us by studying at a higher level. Before we can have a conversation about process, however, we need some kind of language for conducting that conversation.

Some preliminary vocabulary for a process conversation

We would like to introduce at this point four terms which we shall use a great deal later on. They are purpose, strategy, outcome and review.

PURPOSE

People read for different purposes. Sometimes they are reading in order to locate a single item of information (‘What was that name?’); sometimes they are reading to acquire several items of a fairly factual nature; sometimes the facts do not matter much but the general argument does, and the reader is trying to grasp a theory. There are, we shall find, very many different purposes for reading.

Now purpose is very important to reading. First, we shall see that the way you read, your reading strategy, can and should vary according to purpose. If your purpose is to locate a single item an appropriate strategy, for instance, is to scan the text quickly. If you are reading to acquire several items scanning will not do. In order to develop your reading, therefore, the first thing you have to do is to be very precise about your reading purpose. Secondly, in order to be able to measure how effective your reading is (and that is certainly essential if you want to improve it) you have to check it against something, and that can only be purpose.

Purpose may seem an easy concept to grasp, and the tendency is to pass quickly over it. In fact, it is in many ways the most difficult of our terms and we shall find that the chapter devoted to it is by no means a simple one. Many problems in the development of advanced reading skills begin here.

STRATEGY

Strategy is the way in which the reader approaches the text. The first thing to understand is that the text may be approached in various ways, according to one’s reading purpose: that is, there is more than one strategy available to the reader. Thus the person who replied that he always reads in the same way, whatever the text and whatever the purpose, is unlikely to be reading well. At the very least he is restricting himself severely in the way he approaches the text. The mark of good reading is to vary one’s strategy appropriately. To do that it helps to know what strategies are available. That will be the subject of our next chapter. Logically, perhaps, we should consider purposes first, but, as we have said, the concept is more difficult to handle than might be supposed, and there is much to be said for beginning with reading strategies, since they are relatively easy to grasp and knowledge of them bears fruit immediately for one’s reading.

An example of a reading strategy is given in the Purpose section above. We have identified it simply as a scanning strategy, which is satisfactory as a verbal label but does not go very far towards helping the reader to recognise it as behaviour in himself, to know when he is doing it and when he is not. In the next chapter we shall outline some techniques which will help him to do this and, of course, to recognise other reading strategies.

...