![]()

CHAPTER II

HOW MANY BOOKS DO BOYS READ, AND WHAT SORTS?

QUESTION ONE had two objects: to find out how many books these boys read out of school and to discover what sorts of books they were. The number of books read in a month by the 1,570 boys was 7,371: of these 4,767 were read by the 936 Secondary School boys and 2,604 by the 634 Senior School boys.

The word ‘books’ is used in this question in a limited sense. It was hoped that the limits—not indeed easily definable ones—would be fairly clear to children who had read to the end of the last question before they started to answer the first, as they were asked to do. This hope was justified, for there were comparatively few entries out of place.1 This total, then, large as it is, does not represent by any means all of the out-of-school reading done by these boys, although it does represent a large portion of it. It is not possible to estimate how large a portion. It is possible to say how many books per boy this represents; this has been done for the several age groups in both sorts of school; and the following table summarizes the result:

TABLE I

BOOKS READ PER BOY OUT OF SCHOOL DURING ONE MONTH

| AGE | IN SECONDARY SCHOOLS | IN SENIOR SCHOOLS |

| 12 + | 5.0 | 3.9 |

| 13+ | 5.5 | 4.3 |

| 14+ | 6.0 | 4.0 |

| 15 + | 5.0 | — |

It seems that the reading habit is firmly implanted in boys at these ages. There are very few who do not contract it to some degree. A record was kept of those who made no entries here, and who may be regarded as highly resistant to this habit. Their numbers are small, as the following table shows:

TABLE II

BOYS WHO MADE NO ENTRIES UNDER QUESTION I

| | IN SECONDARY SCHOOLS | IN SENIOR SCHOOLS |

| AGE | % | % |

| 12 + | 3.6 | 3.9 |

| 13+ | 0.5 | 2.8 |

| 14 + | 4.0 | 5.9 |

| 15 + | 1.8 | — |

To attain the second object, the discovery of what sorts of books the boys read, meant first a great deal of assorting, much of it arbitrary and dependent on the judgment of the investigator, and, later, some calculations, open to all the objections mentioned in the Introduction.

The problem had been anticipated, and the children were asked to ‘say what sort of story it was: school story, detective story, story of home life, adventure story, love story, historical story, or collection of stories (e.g. an Annual)’. These categories had been arrived at in a small preliminary investigation and through the suggestions of teachers. It was thought desirable to add five further categories: humour, sport, travel, biography, technical.

Into these twelve categories the seven thousand books were placed. The children’s own statements about the sort of story were useful, but were not felt to be binding. Even so, difficulties cropped up. For instance, many adventure stories read by boys (though few written for boys) have ‘a love interest’; similarly, love stories frequently involve adventure. In such instances the investigator had to follow the boy’s own judgment or to make a decision for himself (often, of course, when he had not read the book). Again, several boys recorded books on angling, and these were entered under the heading ‘Sport’; at the same time one or two books on such topics as woodcraft and canoeing were entered under ‘Technical’. For such decisions no excuse is offered; the investigation has been carried on only on the assumptions that neither its data nor its methods are meticulously exact.

What amount of attention do boys give to the various sorts of books they read of their own free will? Does this amount vary from age group to age group? If so, in any significant way? Can any inferences be made about the quality of this attention? Or about the ‘interests’ of the boys?

To discover the ‘amount of attention …’ was a matter of adding up, simple but laborious.

The total assigned to each category in each age group was found. Upon these totals the following tables and remarks are based:

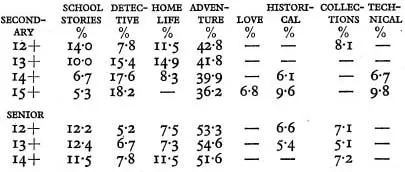

TABLE III

The twelve categories used in this classification were: school story, detective story, story of home life, adventure story, love story, historical story, collection of stories, and humour, sport, travel, biography, and technical. The total number of books specified by each age group was assigned to these categories, and the percentage of this total which each category formed was calculated. Only those categories which scored above 5 per cent are recorded in the above table; where there is a blank in this table that category scored less than 5 per cent.

The curious reader may like to compare this table with the lists of the most popular Adult Books and Authors in Tables IV, V, and VI, on pages 36, 50, 51, and 52.

The changes from age to age are interesting. Are they significant? Certain tendencies—such as progressive declines and increases—are apparent. This suggests that the percentages given above are not chance arithmetical results, that the data and methods of the investigation, if not precisely exact, are valid. It suggests that the figures are related to continuous processes of change—such as are to be expected in the growing boy.

What, then, are the changes from age to age? And, equally important, what is the position at each age? Perhaps the best way of answering these questions is to take the categories one by one.

SCHOOL STORIES

In Secondary Schools the amount of attention given to school stories progressively declines as the boys get older, until at the age of 15+ such stories score only just over 5 per cent. At this age, moreover, more attention is given to books in five other categories, whereas at 12+ school stories rank second to adventure stories. All this is comprehensible enough. At 12+ school is still a very absorbing world to the schoolboy, and for most boys the Secondary School is still new and exciting. His position in this world is a source of close personal interest and in a perfectly normal way he turns to literature for the enlargement of his experience in this sphere of life. And like many an adult reader he goes to fiction for recompense. His position in the school world is not what it might be; he finds himself restrained, thwarted, perhaps humbled. Nor has reality yet tamed his capacity for fantasy. Therefore he seeks satisfactions denied to him in his own everyday school life and finds them in his stories of schools that never were, of unusually ingenious boys, and of remarkably simple masters.

The people who provide these stories often know quite precisely what they are doing. In the Writers’ and Artists’ Year Book for 1932, in an article on ‘Writing for the Juvenile Market’, this fresh and direct advice is given: ‘Get your idea, bring your mind back to your own schooldays, and write of the things you always wanted to do but lacked the courage.’ 1 It is evident that any one who aspires to success in this ‘market’ needs to preserve his capacity for fantasy.

The boys who read these books are usually equally well aware that the characters and events are refinements upon the actual. This does not impair their enjoyment. Nor should it. Aristotle himself looked to art to realize the potential in the actual, and preferred a probable impossibility to an improbable possibility.2

At the same time the remarkable popularity of Tom Brown’s Schooldays at 12+ and 13+ shows that they appreciate the fairly sober and authentic record.

As he progresses through the Middle School, the boy becomes adjusted more or less comfortably to school life as it is and he becomes less interested in school life as it never was; he himself approaches in stature, and perhaps in prestige, the heroes of the Upper School and his values begin to adjust themselves to a world in which the distance between the hero and the normal is narrow or imperceptible; the outside world comes closer to him, he wants a job; he finds that relations with his family and friends, female as well as male, are less stable than he had supposed; and his reading interests make a corresponding move to books more closely derived from the social and economic conditions of the world outside.

Thus the school story receives its death-blow. For each boy interest in it must wither away, as inevitably as his schooldays must draw to a close. What is equally true—and what grown-ups do not easily appreciate since they are no longer schoolboys—is that school stories are a part of school life. It seems probable that they are an essential part of school life, that they make a peculiar contribution to the emotional development of the schoolboy. This is not to say that such stories will persist as we know them. During their short history—a history contemporary with and parallel to the growth of the school system which has disseminated literacy—they have already changed in form and content. Such changes will continue, together with changes in the organization and management of schools.

Naturally, also, the stories will vary in merit, as they do to-day. Their merit will depend, as it does, on the quality of the minds producing them.

It is worth insisting, perhaps, that the decline in interest in school stories has not resulted, at 15+, in its extinction. Such stories still represent more than 5 per cent of this out-of-school reading. Many...