![]()

p.1

Part I

Introduction

![]()

p.3

1 Heritage of death

Emotion, memory and practice

Mattias Frihammar and Helaine Silverman

Prologue

It is as if a gigantic scalpel has separated the tip of the cape from the mainland, leaving a brutally distinct incision that runs all the way through the otherwise idyllic promontory (Figure 1.1). The sides of the gap are sharp and the width of the waterway makes it impossible for people to reach the other side. To any visitor, it would be obvious that this deliberately made wound in the landscape will never heal.

This dramatic scenery was meant to be created on Sørbråten, close to the island of Utøya in Norway where on 22 July 2011 a disgruntled lone shooter systematically murdered 69 of the 560 youngsters attending the Workers’ Youth League annual summer camp. The cut – as a memorial – was meant to let the national trauma turn into a forever unhealed scar – an incantation that something like this should never happen again.

In the example of Utøya, the artist of the memorial chose a subdued but clear tone. Placed in nature – for the event occurred in nature – the memory would not be tied to an erected monument but, quite the contrary, to an absence: a radical removal of trees, roots, soil and rock that would leave a void echoing of the tragedy. There was a conceptual similarity to Maya Lin’s gash in the earth in Washington, DC, commemorating the Vietnam War’s fallen soldiers. The use of absence as a manifestation of loss also recalls the two pits at the September 11 memorial at Ground Zero in New York City. Like them, the Utøya design was architecturally powerful and affective, intending to provoke a strong emotional response (also see Knudsen and Ifversen 2016).

However, even if a memorial design is given permission by authorities, receives appreciation from relatives’ organizations and is lauded around the world, it may be difficult to construct the actual physical remembrance of a terrible and despicable event, for not everyone may want to continue to feel affected by it. Indeed, in the case of Utøya local neighbors protested the memorial and managed to stop the project. Their reason was both paradoxical and easily understandable: they did not want to live in proximity to a memorial that made them remember the gruesome event, in a milieu that constantly made them recall the day they had to pull dozens of dead and wounded teenagers from the sea. Yet another paradox: the attractiveness of the intended memorial became an obstacle. Being perceived as having high artistic and architectural qualities, the memorial was expected to appeal to tourists. This would disturb the much appreciated tranquility of the place. The inhabitants did not want their quiet hometown to develop into a famous tourist site. In September 2016 the Norwegian government decided to look for another way to honor the Utøya dead to avoid a bruising dispute.

p.4

In thinking about memorials it is worthwhile to recall Sarah Humphreys’ well-known statement:

(1981: 12)

Her appreciation leads us to the focus of this edited volume on the heritage of death as manifested in landscapes of emotion, memory and practice.

Introduction

The Utøya case is an example of the tensions surrounding dark events and particularly their memorialization. The ways societies remember their lost ones both mirror and constitute their values and cultural self-awareness. Throughout human history death has been ritualized and framed with reminiscent practices and material markers to remember the ones who have passed away. As is well recognized, death is the greatest of the life crises (Humphreys and King 1981) and societies have always created ways to cope with and explain it (Bloch and Parry 1982; Hertz 1960 [1907]). Notions of death are formed by society (Durkheim 1952 [1897]) and the inevitable awareness of human mortality (Palgi and Abramovitch 1984: 385) has been a crucial dimension of social organization (Binford 1971; Morris 1992; Saxe 1970). As society has changed so, too, has its way of thinking about and dealing with death (Ariés 1974, 1980).

p.5

Contemporary Western society copes with death in its own particular and readily identifiable ways. For instance, there is a “modern strategy” of interpreting the issue of death as a medical and rational concern – death can be defeated by a healthy lifestyle and medical care – a perspective that ultimately attaches a taboo to the inevitability of death (see discussion in Palgi and Abramovitch 1984). There is also a “post-modern” reaction to this scientific approach, exemplified by the renowned social theorist Zygmunt Bauman (1992), by which mortality is constantly deconstructed and rehearsed in different practices and cultural expressions. As such, death becomes part of the individual’s lifestyle (this is especially clear in David Sloane’s contribution to this volume, Chapter 14). And death today is being reconceptualized as heritage – “a contemporary product shaped from history” (Tunbridge and Ashworth 1996: 20). Yet we should recognize that death has always shaped heritage. In this way its heritagization can be seen as “a human condition” rather than an exclusive expression of modernity (Harvey 2001: 320). By way of example, Lennon and Foley argue that “Tourism to battlefields, to the graves of the famous, the infamous and the merely affluent and to the locations of infamous deeds is by no means a phenomenon associated with the modern world” (2000: 4).

The many heritages of death change in shape, content and effect over time. Indeed, death – which was medicalized and marginalized during the last century – is once again part of the public discourse, including around heritage. Today these heritages form a wide range of expressions with personal, sectoral, national and international consequences as well as economic structures, domestic and international political repercussions, contests over memory and implications in new constructions of identity. Heritages of death are vernacular as well as official, sanctioned as well as alternative. And, importantly, death is one of a growing range of phenomena that has been adapted and heritagized to suit the tourism industry. Indeed, the most notorious site of death, Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp, encompasses all of the above-mentioned domains and presents them at the highest level of public recognition: the UNESCO World Heritage List – but not easily (Young 2009).

The multifaceted aspects of the heritages of death are open for controversies and tensions. Who is behind the heritagization effort (private individuals, private sector, public sector, and at what scale – local government, national government and so forth)? Who is the target group? What or who is to be remembered? If a tragedy, is it the victims, the perpetrator or the tragic incident in itself? Is there shame over what happened? Pride over the bravery of the victims or their relatives?

And what is the proper modus when physically memorializing tragedy? Shall the monument celebrate life and abjure death? What emotions are elicited among different actors by memorials? How do visitors, relatives, neighbors and authorities experience them? Do different actors interpret the places in the same way? Who wins the contest over the memories – the monument or the visitors?

p.6

The notion of death oscillates between the material and the intangible dimensions of existence. Thus, while memories are atomically ephemeral, memories reside in place. The body/the grave/the memorial is a tangible reminder of what has been lost, a material trace that calls to be taken care of. The way individuals, families and societies deal with the heritage of death mirrors how they perceive themselves.

This book is about heritages of death and deals with such questions. One premise is that loss has a direct bearing on the concept of memory. Mortuary practices themselves are important in the generation of social memory (Cannon 2002; Carmichael et al. 1994; Kuijt 2001) and inform identity (Chesson 2001). Death is a symbolic and social arena offering opportunities for the representation – indeed, assertion – of self and group (Morris 1989). When death occurs in plural, as in times of war or catastrophe caused by nature or technology or by lunatics with arms, it calls for collective action and common interpretation. As Peckham argues, “Traumatic events in the past can become so deeply imprinted on a group’s collective memory that they become an indelible part of its identity” (2003: 212). Certainly this is the critical narrative about the impact of the Holocaust on the Jews, the genocide perpetrated on the Armenians by the Turks and – unfortunately – so forth.

Death is an emotional domain: “within human society it is a near universal that death is associated with emotionality” (Palgi and Abramovitch 1984: 399), and what we see in the heritage and heritagization of death is a production of emotion. Physical venues of death, contemporary performances and their associated narratives call forth emotions: pride (the glory of the Masada suicide: Bruner and Gorfain 1983), revulsion (concentration camps: Rapson 2012), faith (pilgrimages: Di Giovine 2015), empathetic pain (African slave route sites: Richards 2005) and so forth.

Our third term in the subtitle of the volume – practice – is informed by de Certeau’s (1984) concept of the “practice of everyday life.” We refer to habitual, unmediated, vernacular cultural performances in society that surround death and the categories of death that are significant to them.

In this volume we bring together a group of disciplinarily mixed scholars to consider heritages of death in Europe, the United States and Australia. The volume derives its strength from its anchoring in richly ethnographic studies that illustrate both general patterns and local and national variations. Through analyses of material expressions and social practices of grief, mourning, memory and commemoration as well as exclusion, resignification and exploitation, the authors probe the meanings and deployment of death in contemporary societies. Here we discuss the major themes of the volume followed by the rationale of its organization in Parts.

Mortuary sceneries

“In Flanders fields the poppies blow between the crosses, row on row, that mark our place . . .”. The beginning of this well-known evocative poem by John McCrae, written in 1915 about the devastation of World War I, dramatically conveys a landscape of death. Battlefields around the world have been sanctified (Foote 2003: 8–9) as magnificent cemeteries and made available for international tourism. The most visited of these are those managed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission of Great Britain and the United States’ American Battle Monuments Commission.

p.7

But a shift in attitudes toward tragedies has occurred in recent decades and dark heritage has changed its expressions. A “new moral politics” has emerged and the twentieth century’s incentives to erect triumphal monuments have faded. We now see openness to the recognition of loss and defeat, and “sites of victory are being re-inscribed as sites of defeat, so that heritage and trauma are being fundamentally realigned” (Peckham 2003: 210). Kwon (2006) refers to “grievous death” to emphasize the scale and/or trauma of conflict-caused tragedy. Their memorials seek to assuage the grievous history of death.

As David Mason (Chapter 9) shows us, such landscapes of violent death are not confined to the territory in which battle took place. The ANZAC memorials he discusses pay tribute to lives lost in a massively unsuccessful campaign far away – in Gallipoli, Turkey. The example shows how landscapes, which cognitively would appear to be profoundly territorialized, may, in fact, be mobile by virtue of the memorials associated with them elsewhere. The Australian landscape is actually scattered with war heritage alluding to Gallipoli. Writing from a conservator’s perspective, Mason discusses the delicate matter of managing those culturally double-edged memorials as an act of balance between reactionary militarism and modern peace-minded ideals.

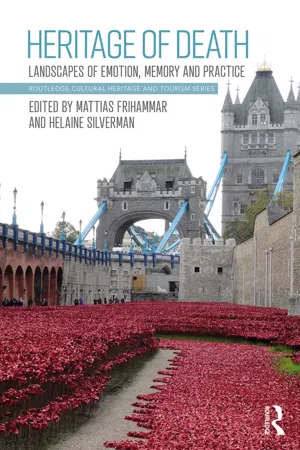

The equivocal Australian collective memory of World War I contrasts dramatically with the heritagization of Britain’s victorious and slain war dead on the centenary of that war. Since 1921 a red poppy has been used as a key symbol in the remembrance of World War I, to such an extent that Remembrance Day today is referred to as “Poppy Day,” even by the Royal British Legion. The everyday vernacular remembrance practices of buying and wearing a poppy activate “interpersonal, emotional experiences of collective mourning and sacrifice” in a way that “erase[s] the violence, done to and by the bodies they commemorate and celebrate” (Basham 2016: 885).

Paul Kapp and Cele Otnes (Chapter 8) approach the poppy tradition from another angle. They reveal that the 2014 “Poppies” extravaganza – for such ...