- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Crime in the Professions

About this book

This title was first published in 2002: This text critically examines the nature and extent of crime and deviance in the professions and how it should be dealt with. Looking in particular at the crimes committed by professionals such as doctors, accountants and nurses, the book offers some innovative solutions to preventing and controlling professional crime. Containing 16 chapters written by some of Australia's leading scholars in the fields of professional regulation and crime control, the book examines the increasing professionalization of the workforce and the changes in the way in which professionals carry out their work.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Background

Chapter 1

Crime in the Professions: An Introduction

Russell G. Smith

Introduction

In recent times, the professions have been subject to a number of changes and challenges. Many new occupations have sought and achieved professional standing; competition policy has altered the way in which professionals are required to behave toward other professionals and to members of the community; new consumer-based regulatory structures have been established to deal with complaints; professional work has lost some of its mystique due to the routinisation of tasks and the increasing use of information technologies; the service basis of professional work has been replaced by a largely commercial one; and the boundaries between the professions have been challenged through market forces and globalisation such that transnational and multidisciplinary professional practices are now starting to emerge. In all, these changes have given rise to what has been described as a 'crisis of professionalism' (Hanlon 1999).

Each of these factors has influenced the way in which professionals carry out their daily work. Each has also created opportunities for professionals to engage in conduct which infringes ethical principles of good practice, specific professional guidelines which govern practice within individual professions, as well as the laws which apply throughout society. This book examines the nature and extent of crime in the professions and discusses the many complex issues which arise in attempting to prevent criminality and unprofessional practice and to regulate professional practice in the most effective way.

The following chapters are based on papers presented at a conference conducted by the Australian Institute of Criminology entitled Crime in the Professions held at the University of Melbourne on 21 and 22 February 2000. Representatives from a wide range of professional groups within the private and public sectors attended along with others from some of the principal professional regulatory bodies throughout Australia.

This book is divided into four parts. The first seeks to define what is meant by professional and to identify which members of the community may be characterised as professionals. Later in this introductory chapter we shall see how many Australians in the labour force claim to be professionals and how the proportion of professionals in the labour force changed throughout the twentieth century. In chapter 2, Kenneth Hayne provides an analytic framework for defining crime in the professions and raises some challenges for those who believe that the topic deserves special attention. In chapter 3, John Western and his colleagues will present some of the findings of the Professions in Australia Project which has documented the attitudes of a sample of University graduates between the mid-1960s and today toward their professional careers and work.

Part two looks at the nature and extent of crime and misconduct committed by professionals by considering those who practice in three professional groups. Andrew Williams (chapter 4) describes the type of criminal and unprofessional activities engaged in by accountants, while Andrew Dix (chapter 5) and Leanne Raven (chapter 6) look at crime in two of the health care professions, medicine and nursing, respectively.

These chapters raise some common themes. It is agreed that criminal conduct is committed by only a very small minority of professionals, although poor standards of conduct arise much more often. The motivations behind professional crime are similar to the motivations which drive other similar types of crime, although professionals' abuse of their unique position of power often creates specific vulnerabilities. There are particular problems in ensuring that professional crime is reported to the authorities, whether by victims or by professional colleagues. Finally, there seems to be a proliferation of ways in which professionals are now regulated and a duplication of complaint-handing mechanisms.

Part three takes up some of these issues and looks specifically at how crime in the professions is dealt with. Margaret Coady (chapter 7) provides an examination of the role which codes of ethics play in shaping professional behaviour and in preventing crime, while Carla Day (chapter 8) provides an example of how one government department—the Department of Defence—developed and uses its fraud control policies to prevent crime. Tim Phillipps (chapter 9) then considers how consumers of financial services can best be protected from misleading and deceptive practices, while Beth Wilson (chapter 10) examines some key issues arising from the public adjudication of complaints against health care professionals. In chapter 11, Sitesh Bhojani describes ways in which to protect those who report professional crime in the public interest—so-called whistleblowers. Part four concludes with Peter Willis's (chapter 12) account of the history of attempts to prevent corrupt practices being engaged in by professionals.

The final part of the book examines issues which have arisen in regulating certain new professional groups and new types of illegality. Anne-Louise Carlton (chapter 13) presents a report on Victoria's unique initiative to regulate practitioners of Chinese medicine and the problems which have arisen in developing an appropriate statutory regulatory model. Graham Brooks (chapter 14) looks at recent changes which have taken place in the regulation of probation officers in England and Wales and how the Home Office's National Standards have restricted the professional autonomy of such officers.Chapter 15 then considers the opportunities for professional crime which the introduction of new technologies has provided. The discussion concludes with a call by Charles Sampford and Sophie Curzon Blencowe (chapter 16) for an integrated approach to be adopted to promote professional values and to avoid crime in the professions.

Definition of Professionals and Professionalisation

Although the following two chapters will address in some detail the questions of how professionals may be defined and what professionalisation is, we should, nonetheless, begin by seeking to characterise professionals in order that we can understand the scope of the problem being addressed.

The concepts of professional and professionalisation have changed considerably over the preceding century. When Carr-Saunders and Wilson (1933) published their seminal work on the sociology of professions in the 1930s, the number of organised professional groups in society was already beginning to grow and they were able to identify some 30 groups of professionals. All, except nursing, were composed predominantly of men and the oldest professions, such as law and medicine, had established procedures for admission of new members and exclusion of those who were unable to attain the specified standards or who were found to have engaged in unprofessional conduct.

Sociologists examined the concept of professionalisation throughout the twentieth century with a variety of fundamental precepts being identified, Johnson (1972, p. 23) divides the definitions of professional into two types: trait and functionalist approaches. The former seeks to list attributes which are said to represent the common core of professional occupations, whilst the latter seeks to distil those elements which have functional relevance for society as a whole.

Some of the traits of professionals which are generally agreed upon include: skill based on theoretical knowledge; the provision of training and education; testing the competence of members; organisation; adherence to a professional code of conduct; and altruistic service (Johnson 1972, p. 23; see also Boudon and Bourricaud 1989, pp. 278–80).

The latest Australian Standard Classification of Occupations published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (1997) distinguishes between professionals and associate professionals. Professionals are defined, using a trait-type approach, as follows:

Professionals perform analytical, conceptual and creative tasks through the application of theoretical knowledge and experience in the fields of science, engineering, business and information, health, education, social welfare and the arts. Most occupations in this group have a level of skill commensurate with a bachelor degree or higher qualification. In some instances relevant experience is required in addition to the formal qualification (1997, p. 103).

The tasks performed by associate professionals include:

Conducting scientific tests and experiments; administering the operational activities of an office or financial institution; organising the operations of retail, hospitality and accommodation establishments; assisting health and welfare professionals in the provision of support and advice to clients; maintaining public order and safety; inspecting establishments to ensure conformity with government and industry standards; and coordinating sports training and participating in sporting events (1997, p. 229).

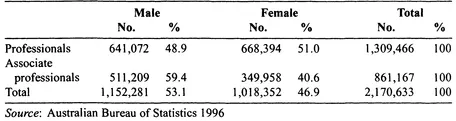

Table 1.1 shows the number of professionals and associate professionals recorded in the 1996 Australian population census.

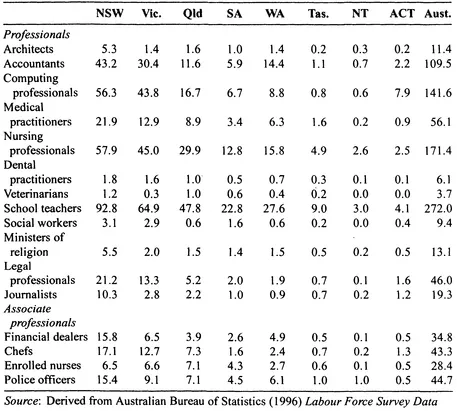

The numbers of employed persons in Australia in some of the more widely-recognised groups of professionals and associate professionals for the various states and territories are set out in Table 1.2.

In the absence of agreement as to those traits which are fundamental to professional practice, theorists have examined the process of professionalisation in order to determine how professions develop and when they can be said to have achieved professional status. One example is that of Wilensky (1964, pp. 142–6) who describes the following 'natural history of

Table 1.1 Professionals and associate professionals in the 1996 Australian population census

Table 1.2 Numbers of selected professionals in Australian states and territories, 1996 ('000 employed persons)

professionalisation': the emergence of a full-time occupation; the establishment of a training school; the founding of a professional association; political agitation directed towards the protection of the association by law; and the adoption of a formal code.

In the context of health care, medicine and dentistry proceeded through these stages a long time ago, whilst nursing has only recently completed its process of professionalisation (Smith 1999b). As we shall see in chapter 13, alternative health care still remains at an early stage in its professional development, at least in Western countries.

Sociologists who favour the functionalist approach have tended to examine professionalisation in terms of its power relationships between professional and client and the purposes for which professional status are sought. Professionalism can also be seen in terms of institutionalised forms of control. In the words of Johnson (1972, p. 45), 'a profession is not, then, an occupation, but a means of controlling an occupation'.

Because professions maintain a specialised knowledge base and are generally self-regulatory, they possess high social standing which is reflected in relatively high levels of income, wealth, power and prestige. This has made the process of professionalisation attractive for other occupations which have taken on the indicia of the long-standing professions in order to enhance their own status (Johnson 1995). The achievement of professional standing was not easily won, however. In the case of nursing, for example, even the achievement of having education based in universities rather than in hospital nursing schools took 50 years of concerted effort by a group of determined women (see Smith 1999b).

Using conventional trait-type definitions of professional, the percentage of professionals in the workforce in Britain increased steadily throughout the last century: four per cent in 1900, to eight per cent in 1950, to 13 per cent in 1966. It was predicted that by 2000, 25 per cent of the workforce would be professionals (Schön 1983, p. 7).

Comparable figures for Australia are 3.5 per cent in 1911, 5.9 per cent in 1947, 9.6 per cent in 1966 and ten per cent in 1976 (Anderson and Western 1976, p. 44). In 1991, professionals and associate professionals made up 22.4 per cent of the total employed labour force. Using the most recent labour force data in Australia, employed professionals made up 17.1 per cent of the total labour force while associate professionals made up 11.3 per cent. Together they comprised 28.4 per cent of the 8.4 million Australians aged 15 years and over in the employed labour force in 1996 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 1996).

In the early years of last century, the conventional wisdom concerning professionalisation was beginning to be questioned with advocates for change such as George Bernard Shaw waging a concerted campaign against the established organisations and professional bodies such as the General Medical Council and British Medical Association (Shaw 1931). More recently, Illich in the 1970s engaged in the wholesale debunking of professional claims to special expertise observing that 'professional cartels are now as brittle as the French clergy in the age of Voltaire' (Illich 1977, p. 38; see also Schön's (1983) account of the crisis of confidence in professional knowledge).

These, and other critics, maintain that professionalism has not always been beneficial to society. Some of its negative effects have been a reduction in competition in the workplace, a reduction in productivity and the adoption of an unnecessarily defensive attitude to criticism or challenge (Boudon and Bourricaud 1989, pp. 278–80).

Invariably the achievement of professional standing requires educational standards to be developed or improved and regulatory mechanisms imposed in order for standards to be set and maintained. At the turn of the twenty-first century, there exists a vast body of professionals who are organised in a myriad of associations, and who are regulated by innumerable agencies. In one sense, professionalisation is everywhere and the activities of professionals over-regulated by both public and private-sector bodies. This idea is not, however, new. Over 30 years ago, Wilensky (1964, p. 143) argued that all occupations were being professionalised but that few would achieve the level of authority which the established professions commanded at the time.

More recently, however, a trend of 'deprofessionalisation' has taken place worldwide fuelled by international initiatives towards free trade, consumer and commercial pressures, and pressures from within professions themselves for increased competition (Paterson 1996, pp. 146–8). Although the recognition of the negative aspects of professionalism has been beneficial in a number of respects, it is a matter of concern that standards of conduct may decline if the professional ideal is eroded too far. In the words of Boon and Levin (1999, p. 67):

Faced with a considerable reduction in privilege and public trust, professionals can either retreat to the view that their practice is purely a business or they can renew their professional commitments and seek new ways of realising the professional ideal.

The Changing Nature of Professional Practice

Professional practice has altered considerably in recent years, largely brought about through changes in social and economic conditions in Western democracies (Hanlon 1998). Mention has already been made of the crisis of professionalism, the emergence of the commercialised professional, and the deprofessionalisation of some aspects of practice in recent years. Four important developments, however, have had a profound influence on the nature of professional practice: the introduction of competition policy; the breaking down of barriers between the professions; globalisation; a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- PART I: BACKGROUND

- PART II: THE NATURE AND EXTENT OF CRIME IN THE PROFESSIONS

- PART III: DEALING WITH CRIME IN THE PROFESSIONS

- PART IV: NEW PROFESSIONS AND NEW REGULATORY APPROACHES

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Crime in the Professions by Russell Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Sociología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.