1.1 The self and the organization in changing societies1

Martin (born in 1959) lives in Ljubljana, Slovenia. He is married and has two children. Martin was raised in a blue-collar family, which was not so well-off. His early decision to have a better life in the future motivated him to study hard in a public high school and continue his education at the state university. In 1977 he was obliged to serve twelve months in the Yugoslav National Army (JNA) in another Yugoslav republic. As a sophomore, Martin joined the Communist party, not out of political belief, but rather in order to use membership as a catalyst for his future career. In 1982 he graduated from the University of Ljubljana and earned a BSc in Economics. Soon after that, he found a job with a very prosperous firm with more than 500 employees. His first position was that of a sales representative, in charge of covering a part of the domestic-Yugoslav market.2 In his job, he did not have to use any foreign language skills, except for the other Southern Slavic languages/dialects used in the other Yugoslav republics. Therefore, he forgot almost all the English he learned at school, as well as basic business German from the university classes.

He was satisfied with his job, salary and with the firm’s offer to arrange additional professional education. He soon got married to Magda and, after the birth of their first child, his firm provided him with a ‘generous’ subsidized long- term loan to enable him to buy an apartment on the outskirts of Ljubljana. With his and his wife’s income, his family could enjoy all the benefits of what was considered a ‘good life’ by former Yugoslav standards. His family purchased a used car, a Zastava 101, a Yugoslav licensed version of the dated Italian model, the Fiat 128. His family was also able to afford two weeks’ holiday per year on the Adriatic coast, in the seaside resort owned by his firm.

Since the end of World War II, many of Martin’s relatives had left Yugoslavia. During the 1950s, some of them escaped for political reasons, after being imprisoned for opposing the Communist regime. In the 1960s, the former Yugoslavia started political and social reforms and became one of the liberal socialist countries. However, the living standard was still far behind the ‘Western’ one, which motivated some of Martin’s other relatives to search a ‘better life’ in Germany. Unlike political emigrants, they often visited their family in Slovenia (Yugoslavia). This was an opportunity for Martin to get some products like detergents and coffee that were occasionally not available in Yugoslav shops. He also acquired certain amounts of hard currency – German marks needed for shopping trips to neighboring Austria and Italy where the family used to buy various ‘western’ products (cheap fashion clothes, trendy toys, etc.).

In the late 1980s, the former Yugoslavia faced significant economic and social problems, while the tensions among the federal republics started to escalate. Unlike five years previously, Martin’s firm was actively seeking partners in the West, just in case something went wrong with the existing common Yugoslav market. Martin gave up his membership of the Communist Party and voted in the first democratic elections held in April 1990.3 In the referendum in December of the same year, Martin and his wife voted for the independence of Slovenia. The culmination as well as the resolution of the crisis happened in 1991, when Slovenia officially proclaimed itself as a new independent nation. This caused military reaction from the ‘federal army’ – JNA. However, after a short period of hostilities, JNA began withdrawing from Slovenian territory. The independent Republic of Slovenia was soon recognized by the international community.4

By 1992, Martin found that nothing was the same as before. His children wanted to watch foreign programs via satellite and started learning English and German. Even Magda, working as the manager of the accounting department of a large enterprise, had to take computer and foreign language classes, as her firm had started to introduce a new information system. She began to work long hours and, for the first time, sometimes even had to work at home during the weekends in order to finish required reports. However, she was well paid and motivated. In Martin’s company, things had changed, too. The former (Yugoslav) market had shrunk significantly, with only a few Croatian firms still cooperating. Fortunately, his company found new business partners in neighboring countries – Italy, Austria and Hungary. One of the major partners from Austria was interested in either forming a joint venture, or acquiring Martin’s firm. Eventually, in 1996, the Austrian partner became the owner of a majority share, while approximately 20 per cent of the ownership was retained by the workers, and the remaining 10 per cent was held by state funds.

Since 1997, Martin has had a new manager – Mr. Strobl, from Klagenfurt (Celovec), Austria. Fortunately, Mr Strobl’s mother is a member of a Slovenian minority in Austria, so he is able to speak some Slovenian. Martin does not like the new rules: coming fifteen minutes late after the start of working hours is no longer tolerated. In addition, each Monday there are short business meetings with Mr. Strobl. Martin is expected to deliver a computer presentation and a spreadsheet with the sales report for the previous week. He has the latest computer technology available, but still often needs advice from his firm’s ‘computer wizard’. However, Martin is still satisfied with his job and respects his new superior, not only because Mr. Strobl is a competent professional, but also because he is trying hard to speak Slovenian. It is also evident that his new boss respects the Slovenian culture and tradition. Sometimes, Martin gets annoyed with Mr. Strobl’s insistence on documented communication within the company. For instance, Strobl insists on keeping a strict record of telephone calls and even e-mails, in order to be able to control relations with each of the firm’s customers. Mr. Strobl also seems to avoid emotional involvement, even in informal situations.5

After the Austrians acquired Martin’s firm, the salaries were raised. Martin owns a new car, a Renault, has paid off his first loan for the apartment and has taken another in order to buy a cottage in the popular lake resort, Bled, half an hour’s drive from Ljubljana. However, the improved standards have their price: besides refreshing his German, which had almost been forgotten, Martin is acquiring new computer skills and is adapting to the new job description. Martin is now supposed to promptly enter all the sales data into the new computer system, as well as meet early sales quotas. The amount of sales significantly affects his salary, as the annual bonus is not awarded to sales representatives who do not meet the performance requirements.

Martin still sees himself working for the same firm until he retires in 2024. However, a possible move to another firm might be an attractive option, if only he were a little younger. The family’s future now requires more planning, as more options are becoming available. Therefore, Martin and Magda took out additional life insurance and health care policies, in order to be better prepared for the years to come. Although their private and professional lives have been reshaped by the environment, they consider themselves adaptable. Changes will certainly go on, and the family will do its best to keep pace.

1.2 Individuals, social entities and change

Change in social institutions and societies ‘at large’ is usually perceived through the changes in the individual’s current quality of life, as well as expectations regarding the fixture.6 The case of the Slovenian family presented in the previous section clearly indicates the motivations to introduce the sweeping economic, political and social changes in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). Still, a more elaborate theory of social change, under the special circumstances of the CEE region, is needed both for scholarly reasons and to provide a more coherent view of the events in CEE to the outside observer. However, one has to be aware that there is no agreement about the course of long-term societal change among Western thinkers. At least half a dozen basic configurations of change (‘theories of history’) are circulating in contemporary social sciences, from models of linear progress via cyclical waves to stagnation and decline. Public visibility and acceptance of these views usually depend on political constellations. Hence, when it comes to explaining transition and transformation only one or two approaches dominate, although more models of development are available. In the forefront we find models of ‘progress’ (e.g. F. Hayek, M. Friedman, M. Albrow) but also of ‘crisis’(E. Durkheim, D. Bell, J. Baudrillard) and ‘decline’ (K. Marx, S. Huntington, J. Schumpeter). Besides such global assumptions about the course of history, we also find ‘general’ and ‘middle-range’ theories often claiming universalistic validity.

Which type of approach is adopted also depends on the kind of academic field or social circle showing interest in societal change. The field of management mostly adopts derivations of the (functional) structural paradigm as developed by scholars like T. Parsons or N. Smelser from the 1940s and 1950s onward (cf. Parsons, 1967/1951, Parsons/Smelser, 1972/1956, Staubmann/Wenzel, 2000). Before turning to societal change (see the older T. Parsons 1962) this tradition first outlines the major social entities – the potential objects of change. The following is a rough and modified application of this general approach, sometimes very broadly also subsumed under the systemic approach7 to ‘society’.

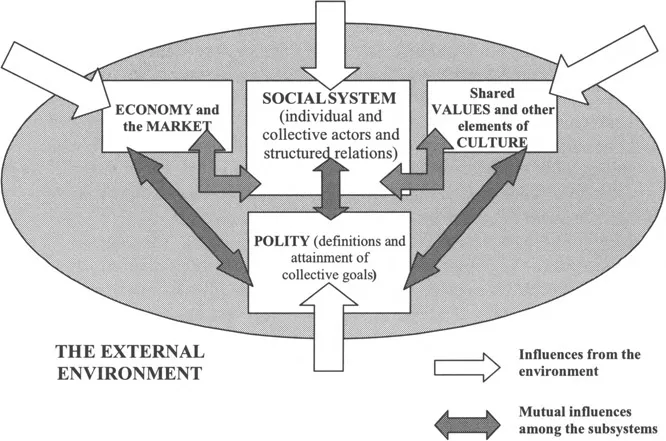

Its components are: (a) the social system – the core of society, defined by interrelating individuals and organizations which act out of structured social positions (e.g. classes, social strata, estates, casts); (b) the cultural system, providing the values, norms, orientation, artifacts, etc., which determine or guide the exchange among the social actors by establishing what is appropriate, how ‘right’ is differentiated from ‘wrong’, what kind of consumption is preferred …; (c) the political system (polity), deciding/attaining collective goals and defining social organizations; (d) the economic system (with the objective of providing goods/services to society in an efficient manner, i.e. by maximizing the output of society’s economic (sub)system within the resources available). It should be mentioned that in the tradition of this paradigm, the ‘social’ and the ‘cultural’ could be understood as two sides of the same coin; one addressing the ‘being’, the other the ‘meaning’ of society. Whereas ‘economy’ and ‘polity’ are meant as subsystems or differentiations of the ‘social system’.

Figure 1.1 General systemic model of a society and the interactions among the parts of the system8

All of the subsystems interact with each other, as well as with the environment (e.g. other societies, nature), providing society with the opportunity to adjust to the changing conditions (or, to ‘develop’, if human history is to be viewed in terms of progress towards more ‘advanced’ forms). Figure 1.1 illustrates the general societal model and its dynamics, including the interactions among its internal components, as well as their interfaces with the external environment. The entirety of these interactions will be referred to as the process of social change,9 which can also be described in terms of modifying relationships among the actors in society10 and/or transforming the culture of a society (and thus referred to as ‘socio-cultural change’) (cf. Parson/Platt, 1973; Preston, 2000).

However, it is assumed that societies do not change in a random manner: the changes are interlinked and take the form of ‘organized’ patterns, as suggested by many social scientists. For instance, an interesting study (Ronfeldt, 1996) singles out four fundamental stages of societal evolution: the tribe (usua...