![]()

Part One

TOWARD THE PERFECT PLAY EXPERIENCE

![]()

1TOWARD THE PERFECT PLAY EXPERIENCE

Polly Hill

Introduction

Many people involved in children’s play share an ultimate goal, no matter what their discipline, their area of play work, or their relationship with children. The goal is to improve children’s play environments and to increase the quantity and quality of children’s play opportunities and positive play experiences. None – except a few dreamers – expects to reach the perfect solution. It is the striving toward that perfection that counts – and that is the topic of this paper.

What then are some basic principles or criteria that can be used to evaluate play experiences? What can be used to evaluate programmes, play environments and leadership techniques? One should start with the end-product: what kind of a human being or adult is desirable? What kind of Canadian, Swede, Britisher, Indian, African? Is there a common denominator? It is proposed that value systems, no matter how different, include the following elements:

1.physical fitness;

2.intelligence;

3.creativity and imagination;

4.emotional stability and initiative;

5.social assurance and co-operation;

6.self-confidence and competence;

7.individuality;

8.a sense of responsibility and integrity;

9.a non-sexist outlook;

10.a sense of humour.

Of course, the child’s home and school are major influences in his/her development. There is ample evidence, however, to indicate that the out-of-school life – the play life – of the child is also a major influence on what he/she will become.

What then are the criteria for a perfect play experience? Several different sources, including instinct, personal experience, practitioners and researchers, have all contributed to the information on which these criteria are founded. Little need be said here about instinct and personal experience, but special note must be taken of practitioners and researchers. There are practitioners who share their philosophies and work experience through their writings – John Dewey, Susan Isaacs, Catherine Reed, Lady Allen of Hurtwood, Arvid Bengtsson, to mention only a few who have published in English. There are the researchers: Jean Piaget on how children learn; Michael Ellis on what play is; Hulme and Massie on where children play in the cities; and Robin Moore and Roger Hart on how children play when adults are not watching. As a practitioner, I have been interested in the Environmental Design Research Association’s concern about the implementation of research. I am also delighted to see that researchers are working more and more with practitioners and in many cases involving the children themselves in the research process. But there are times when I worry about researchers. For example, I always knew someone, somewhere, would research children’s use of mud. Well, somebody did. They put the data into a computer and came out with the astonishing finding that children preferred wet dirt to dry dirt. But will this well-documented, sensitively gathered evidence on children’s love of mud and creative uses of mud convince recreation administrators and school janitors to put a mud hole in every playground? Or will this study instead collect dust? Dry dust?

We are in the computer age – an era of sophisticated research. We need these in-depth looks at what may be ignored or taken for granted, but, as one researcher said at the International Playground Association conference in 1972, practitioners must act, they cannot wait for us to prove that what they are doing is right or wrong.

Another example of research, which put forward recommendations that were acted upon and became government regulations, set play opportunities in council housing in England back 30 years, in my opinion. I am referring to Children at Play, a publication of the United Kingdom’s Department of the Environment (1973). This study reported research based on existing playgrounds in council housing. It resulted in the Department of Environment Circular No. 79-12, which demanded a specific number of seesaws, swings, slides and roundabouts for each project; the bigger the project, the higher the number of each item required. What went wrong? The researchers were gathering the wrong data. They counted the times the children used the only equipment available to them, which happened to be traditional playground equipment. They must have had a computer code for seesaw, and none for mud. They did not consult the practitioners until the review copy stage. Eventually, the National Playfield Association managed to inject a chapter on adventure playgrounds, but too late to affect the Design Standards Circular.

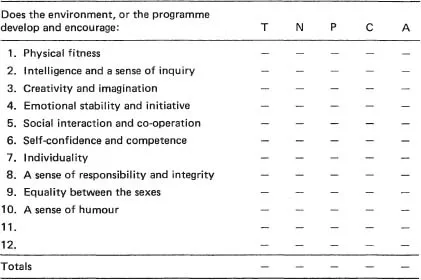

It is the action criteria that I want to speak about: how to judge a good play experience, in order not to perpetuate the useless and meaningless; instead, how to create opportunities for play that nurture the child’s total development. Figure 1.1 lists my criteria for judging the ‘perfect’ play experience. Other criteria may be added, or some of these omitted. First, each of the points will be explained and then used to rate five different environments or play programmes.

Physical Fitness

Physical fitness involves activities and equipment that develop the large muscles of the body in the arms, legs, neck, torso and heart. From birth, children stretch, pull, push, move from place to place and gain control from random action to purposeful action, all without anyone telling them how. As children grow older, adults have a tendency to instruct, to coach; however, there are a myriad of physical activities that children do that are not taught. They learn by doing. No one ever taught a child to climb a tree nor does a tree have built-in safety controls. In design terms, this means providing opportunities that require the use of the large muscles and present a challenge. Safety features should be designed for the unexpected slips, for being pushed, etc., but should not restrict the challenge. If there is no incentive to go higher, for instance, the child’s physical development will not be stretched and he/she will soon get bored.

Intelligence and a Sense of Inquiry

The development of an inquiring mind requires as much exercise as developing the body muscles. Children need opportunities to explore, to experiment with cause and effect and with solving real problems. They need to work with things they can move and change. In design terms, it means an environment with a great deal of variety, with lots of loose materials and natural materials that can be studied and moulded. It also requires a leader who can act as a catalyst.

Creativity and Imagination

We know very well how to kill creativity, but little about how to nurture it and keep it alive. One still sees identical bunny rabbits on recreation centre and school walls, drawn to the model of the instructor. Children need practice and exercise in expressing themselves, in whatever media are available, or just with themselves and their imagination. There is a process that I call ‘from mud pies to murals’ or – to borrow from John Dewey – ‘learning through experience’, a process that continues throughout life. Creative adults are desperately needed, not ones who paint murals necessarily, but ones who can deal creatively with the world’s ills. In design terms, the answer is the same as for developing intelligence: lots of variety, lots of loose material – lots of stimulation.

Figure 1.1: Criteria for the Perfect Play Experience

Note: For the purposes of this chart perfect means: toward perfect, good, positive, the opposite of bad, sterile, generating negative behaviour.

Emotional Stability and Initiative

How can emotional stability be fostered through play environments and play programmes? Perhaps here, more than anywhere else, a play worker can be the catalyst, intervening when children bully each other or ostracize one of their peers. Children take the initiative when they feel good about themselves. They search for new experiences and emotional satisfaction. (The need for a play worker to raise the quality of play experience for the individual child becomes more and more evident as this list proceeds.) In design terms, a play programme with a leader is required. In particular, a programme is needed which gives the leader time to know the children, to help them where needed, and which has the kind of environment that honours and encourages initiative.

Social Interaction and Co-operation

The primitive strivings of young children to share, to co-operate and to make friends must be recognized. Children need opportunities that bring them together, that give them something to do together, to laugh about, to exchange ideas about, and that will give them practice interacting on a social level. In design terms, social play can be encouraged by play houses; by materials to make their own huts; by blocks and boards for younger children to construct into houses, stores or spaceships; by places to meet and talk; by lots of loose materials with which to work – together.

Self-confidence and Competence

Doing well and knowing how to do things involves many things. It means experiencing and trying in an atmosphere that is uncritical and not too demanding. It means going at one’s own pace, in one’s own time. In design terms, this means a wide variety of choices and challenges.

Individuality

To conform without meaning to the dictates of a gang, to be afraid of being an individual, is a stage of development that sometimes needs the tender intervention of a parent or a play worker. Here again, play programmes that honour differences and do not ridicule them can do a great deal to help develop a child’s individuality. In design terms, it means programmes which allow for a great deal of freedom and which have leadership that is not directive in nature.

A Sense of Responsibility and Integrity

Giving children responsibility – especially for something they love, such as an animal – helps them relate to the need to take responsibility for their own actions. Play programmes that foster responsibility taken positively, in a play situation, can have long-lasting effects. In design terms, it means places to house animals and freedom for a large degree of child control in the programme.

Equality Between the Sexes

Even though children in the middle years (7-12) tend to play separately and have gangs of their own sexes, programmes can do a lot to ensure that equality is maintained and not flaunted. In design terms, it means offering programmes that are of interest to both sexes and are not competitive between them or sexist in nature.

A Sense of Humour

Can a play programme develop a sense of humour? Possibly not. This seems to be basically the family role, starting at babyhood, but perhaps programmes can awaken the dormant sense that has not been stimulated, and recognize and cater to the natural gaiety of children.

If each play environment and play programme is evaluated according to these criteria, perhaps one will pause and not be content to go half-way, supplying only a physical play environment – as is happening so much here in Canada – with nothing for the mind or the development of creative power.

Return now to Figure 1.1 and score each type of play environment as described below. Score each type of play environment for each criterion from ‘0’ (no value) to ‘10’ (highest value). Then add the scores for each type of play environment.

T. Traditional Playground

Imagine a swing, slide and teeter-totter made of iron, or their modern equivalents made of wood, with rows of logs, stuck in the ground at different heights, usually in a semi-circle; a single culvert pipe on its side, and a 2 m x 2 m sand box with 5 cm of dry s...