![]()

Part I:

York

![]()

1

‘Places to Hear the Play’: Pageant Stations at York, 1398–1572

Anna J. Mill’s valuable article on ‘The Stations of the York Corpus Christi Play’ uses only those lists which state more or less exactly where these stations were. However, she observes that ‘others … may, with caution, be derived from the names of those who pay rent, if the location of their houses is known and is on the route indicated’.1 This sounds daunting: it is just not possible, even from the comparatively full York records, to find out exactly where two hundred and more named people lived over a time span of nearly two centuries. But one can, with caution, proceed a little further than she did. At the end of her article she provides a chart of station sites, but she makes no attempt to correlate it horizontally and has no particular interest in the names of lessees if no location is provided for them. But even lists that consist solely of names can be made to yield information when they are seen as part of a larger pattern. At the end of this article I provide a chart that not only gives the names of all station lessees in all the surviving lists, but also attempts to site them along the pageant route in what I calculate to be their correct places. Much of the pattern is provided purely from the internal evidence of the lists themselves.

As one reads through the lists, certain names become familiar: names like John Lister, Matthew Hartley, Thomas Scauceby, William Caton, and Alan Staveley. They not only appear more than once, they turn up at roughly the same place in the lists each time. Earlier attempts have tended to assume, rather unthinkingly, that Station 8, for example, will always be at the same place, but it seems much more sensible to assume that if the same person turns up for several years running at, say, Stations 10, 8, 11, and 9, that the person and the place are constants and that the numbering of the station is a variable. One can check this for stations whose places are known: between 1538 and 1572 the Minster Gates station is variously number 8, 12, 7, 11, and 9. Now the station-holder ‘at the Mynster yaitis’ in 1538, John Lister, is just finishing a run of eighteen years, for nine of which (1520–8) we have consecutive records, with varying station numbers. His neighbour ‘in Stayngayt’, Matthew Hartley, seems to have kept the same station, with one short break, for twenty-nine years (1523–51). Not many others show such remarkable runs (partly because there are breaks in the evidence, as one can see from the dates of the surviving lists), but there is an impressive amount of short- and middle-term continuity which, of course, suggests that hiring stations was a profitable affair! Then one finds the groups of associates: for example, from 1501 to 1527, a group of people (John Caldbek, Richard Ashby, John Blakey, John Myres, George Churchman, and John Cowper) take turns to pay for Station 2, never all at once, but singly, or in pairs, or even threes, with enough permutations for it to be obvious that they are neighbours, if not actually a syndicate.

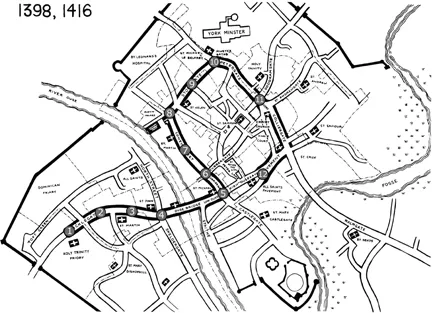

Chronological same-person runs like these provide us with the horizontals for our table. The verticals are provided by the pageant route itself. The actual route remained the same for the whole period; only the stopping-places varied in number and location. Along this route, the same sequences of names will turn up from year to year, though not always in successive years: eg, Hartley, Lister, Wylde, and Nicholson (1526–8); Halliday/Hudson, Scauceby/Kilburn, and Mrs Toiler (1468, 1475). If one can pin down a location every now and then, either from information in the lists themselves or from external evidence, then the other names in the sequence can be spaced out along the intervening stretch of street: we are, after all, dealing with a real city, not a theoretical piece of elastic. The result, though some of the placings can only be relative (at what number in Petergate did Alderman Gillour reside?), is more complete than could at first be imagined possible.

One can assume that, on the whole, these stations are outside the dwelling houses of the people named on the lists. The 1416 ordinance lays down that the play shall be played ‘ante ostia et tenementa illorum vberius et melius camere soluere et plus pro commodo tocius communitatis facere voluerint pro ludo ipso ibidem habendo’:2 nearly a century and a half later, the 1554 ordinance warns that ‘suche as woll haue pageantz played before ther doores shall come in and aggree for theym before Trynytie Sonday next’.3 The formula in the lists is ‘ante ostia tenementi sui in Staynegate’ (1454), ‘ante ostia sua ad porta[m] Sancte Trinitatis’ (1468), ‘at my lady Wyldes’ (1538), ‘ageynst Heryson doore’ (1551), and ‘at William Gilmyn hows’ (1572). Occasionally the indication is made that a lessee does not own the house he lives in, but merely rents it: ‘tenemento in tenura sua’ (1454, Station 1). The word tenementum means simply a ‘building’ as distinct from a messuagium, which can include grounds: in 1454 the church of St John Ouse Bridge is described as a tenementum.

The first two lists (1398 and 1416) are anomalous in that they refer to some named houses as belonging to people who are already dead. John of Gyseburn, mercer and lord mayor, at Station 3, died in 1390, well before the date of even the first list. In the 1416 list, two more, Adam del Brigg (died 1404) and Henry Wyman (died 1411), are marked out as ‘quondam’. However, the writer of the 1416 list is concerned mainly with establishing the official status of that of 1398, so he quotes it almost verbatim. Houses (or business premises: the distinction is a false one in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries) are occasionally known by the name of their builder, but these two lists are an exception of their kind. All other lists until very late (1551, 1569, and 1572) are concerned with recording payment from individuals rather than marking out locations, and every person on whom a check can be made appears to have been alive at the time at which payment was recorded, though some narrow margins are found. John Bateman died in December 1521, and Lady Agnes Staveley is possibly paying the fee already contracted for by her husband Alan, who died in June 1522.

The one exception is this at-home rule is the occasional hiring by a religious house. The abbot of Fountains brings a party to the station at St John’s Micklegate in 1454; St Leonard’s Hospital, which is not on the route,4 hires the nearest station, the one at the Common Hall, in 1454, 1468, 1499, 1506, and 1516. The Austin Friars (1454) and the Guild of St Christopher and St George (1468) are on their own doorstep at the Common Hall Gates.5 The other major exception is the mayoral party, to which we shall return.

One is able, though very rarely, to locate a particular house exactly through wills, mortgages, and conveyances. This area is not as promising as it might seem: very few official records of property transactions exist, and both they and wills are disappointingly vague: ‘To my sonne Peter … my gret hows in Coppergate & my landes, etc. in the parish of Alhalows upon the Pament’ (Sir John Gilliot 1509),6 or even more tantalisingly, ‘my chefe place in Yorke that I dwell yn’ (William Nelson, 1524).7 A house can be located at least along a particular stretch of pageant route, however, if one knows the parish in which the owner lived or, as it appears in the wills, in which he died and was buried. Central York was graced with a large number of churches and a correspondingly large number of parishes, and a satisfactory number of these parish boundaries intersect the roads along the pageant route, as the map below shows.

I have superimposed a map of parish boundaries over the existing street plan of York by John Harvey. Thus, if we know that William Moresby (1506, Station 4) asked in 1517 to be buried before the image of St Anne in the churchyard of St Michael Spurriergate,8 the odds are that he lived in the parish and that his station must therefore be located between the east end of Ouse Bridge and the end of Spurriergate, not at the west end of Ouse Bridge. The exception, after the Cathedral, is Holy Trinity Priory, which seems to have been popular outside its strict parish boundaries. Richard Gibson, cord-wainer, who rented Station 3 in 1499, 1501, and 1508, whom one would have thought would have been well down Micklegate in St Martin’s parish, went to Mass ‘at Trenites in Mekilgate’.9 John Ellis, senior, with whom he rented the station in 1499 and 1508, was buried there. He also turns out to have owned the Three Kings Inn, which appears under its own name in the station lists of 1551 and 1554, as he leaves it to his wife Joan in his will:

meum messuagium cum pert. in Mikkilgate, vocatum Les Thre Kingges, sicut iacet ibidem inter terram W. Holbek ex parte orientali et terram quondam W. Shirwod ex parte occidentali, unde unum caput buttat super regiam viam ante et super quoddam vicum vocatum les Northstrete retro.10

This still does not tell us precisely where the Three Kings Inn was, but it does show that the inn was on the left-hand (north) side of Micklegate: ‘les Northstrete’ in the early sixteenth century also included Tanner Row.

Map of pageant route showing parish boundaries.

Occasionally one can pick up a location from other sources, such as the House Books and the Memorandum Books for the period.11 Thomas Wells, goldsmith, who rented Station 4 in 1486, was witness to an affray, recorded in the House Books on 27 July 1496, between Richard Thornton, sheriff, and Ralph Nevill, esquire:

Thomas Welles saith wher as on Wednesday at viij of the clok at after nowne … the said Ric. Thornton and the same Thomas satt togedder on a stall to fore the dore of the said Thos, and Sir Ric. York, knyght, and the said Rauff Nevill come togedder in armez from Skeldergate, and when they come in mydds of the strete that goeth toward Ouse brigge, Sir Ric York said he wald bryng the said Rauff to his loggyng and he said he shuld not for he wold rest hym on the above said stall and then Ric. Thornton and the said Thomas bad hym good evyn and put of theyr bonets, and the said Rauffe furthwith drewe his swerd and then and ther made assaut opon the said Ric. Thornton, and witt that Sir Ric. York toke the said Rauffe by the arme and asked him what he wald doo and pulled hym bake.12

Thomas Wells lived at the junction of Skeldergate and what is now Bridge Street, opposite St John’s Church. Because the two armed men had come from Skeldergate and were in the middle of Bridge Street before the argument started, Wells seems to have lived on the same side of the main road as the church, also the left-hand side of the route.

One is, of course, haunted by the possibility that somebody, at some point, may have moved house, or at least asked to be buried somewhere other t...